Dungeons & Dragons rolls the dice with new rules about identity

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

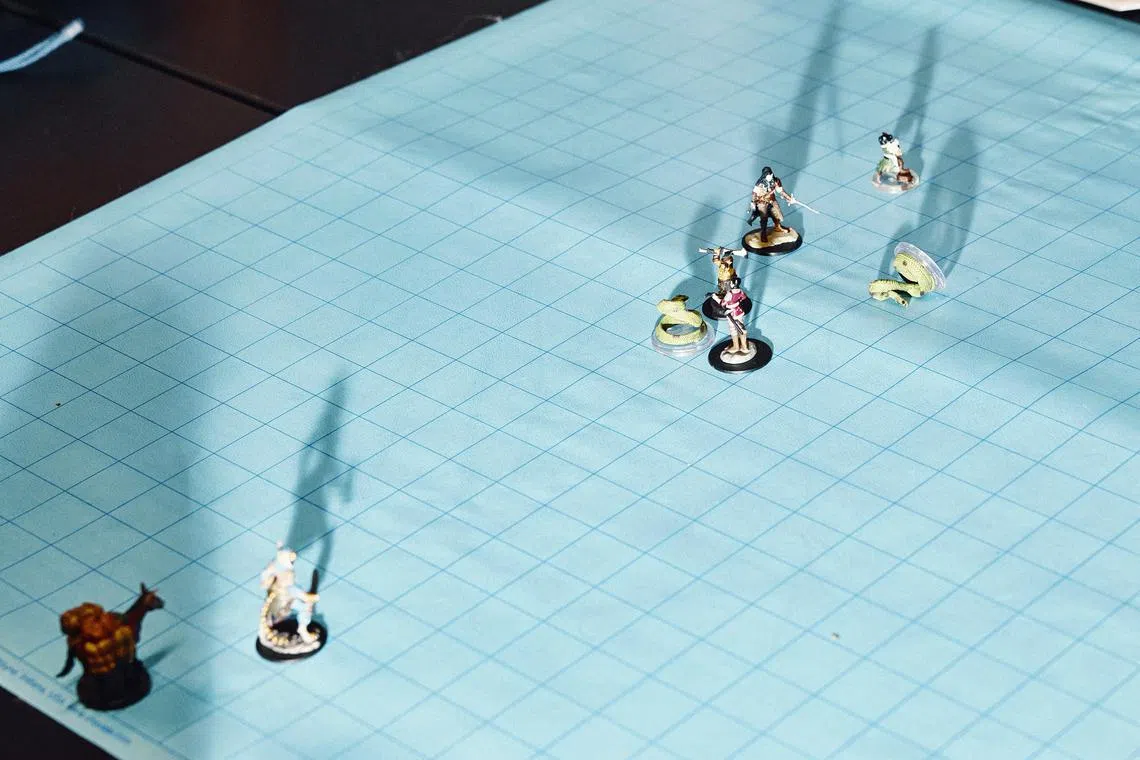

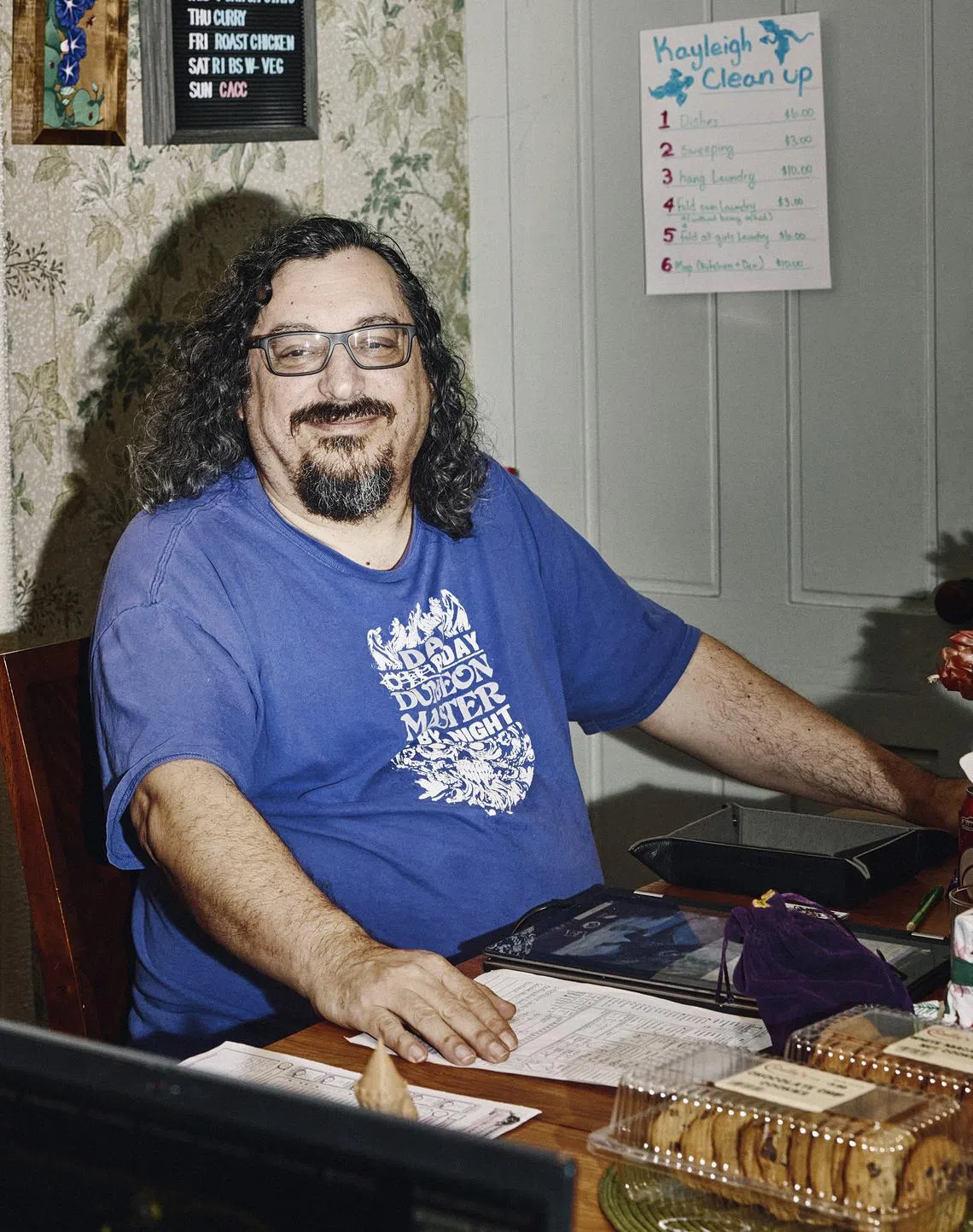

Kyle Smith plays a game of Dungeons & Dragons led by Dungeon Master Jeff Parrish.

PHOTO: SIMON SIMARD/NYTIMES

While solving quests in Dungeons & Dragons, the gamers who role-play as elves, orcs and halflings rely on the abilities and personalities of their custom-made characters, whose innate charisma and strength are as crucial to success as the rolls of a 20-sided die.

That is why the game’s first significant rule changes in a decade, which became official in autumn 2024 as it celebrated its 50th anniversary, reverberated through the Dungeons & Dragons community and beyond. They prompted praise and disdain at game tables everywhere, along with YouTube harangues and irritated social media posts from Mr Elon Musk.

“Races” are now “species”. Some character traits have been divorced from biological identity; a mountain dwarf is no longer inherently brawny and durable, a high elf no longer intelligent and dexterous by definition. And Wizards of the Coast, the Dungeons & Dragons publisher owned by Hasbro, has endorsed a trend throughout role-playing games in which players are empowered to halt the proceedings if they feel uncomfortable.

“What they’re trying to do here is put up a signal flare, to not only current players but also potential future players, that this game is a safe, inclusive, thoughtful and sensitive approach to fantasy storytelling,” said Mr Ryan Lessard, a writer and frequent Dungeons & Dragons dungeon master.

Players divided over changes

The changes have exposed a rift among the game’s players, a group as passionate as its pursuit is esoteric, becoming part of the broader cultural debate about how to balance principles like inclusivity and accessibility with history and tradition.

Mr Robert Kuntz – an award-winning game designer who frequently collaborated with Mr Gary Gygax, a co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons – disliked Wizards of the Coast’s efforts to legislate from above rather than provide room for dungeon masters, the game’s ringleaders and referees, to tailor their individual campaigns.

“It’s an unnecessary thing,” he said. “It attempts to play into something that I’m not sure is even worthy of addressing, as if the word ‘race’ is bad.”

The changes to Dungeons & Dragons, which gamers commonly call D&D, may fit into the corporate world’s pursuit of diversity, equity and inclusion, but they are also part of a financial strategy for Wizards of the Coast.

Players responded tepidly to the fourth edition of Dungeons & Dragons in 2008, when the game was more punchline than blockbuster movie premise. The Big Bang Theory (2007 to 2019) was not yet television’s highest-rated comedy, and the cultural phenomenon of Stranger Things (2016 to present), whose 1980s characters are fluent in D&D jargon, was years in the future.

“The D&D audience was shrinking,” said Mr Jeremy Crawford, the game’s lead rules designer. “The game was becoming so tailored to just one way of playing that it was not feeling as inviting as we knew the game could be.”

Players desired greater leeway in creating their characters, Wizards of the Coast executives said in defence of the new rules. The 2024 Player’s Handbook is the fastest-selling publication in company history, it said, and its new guide for dungeon masters is already in reprints.

The role-playing game replaced “race” with “species” and divorced several character traits from biological identity.

PHOTO: SIMON SIMARD/NYTIMES

In addition to its species, each character in Dungeons & Dragons is assigned a class such as bard, druid, rogue or wizard. During quests, the abilities and corresponding skills of characters manifest in ways that can complement or undermine one another.

A bard typically has a leg up when it comes to charisma, one of the game’s core ability scores. When his party finds itself negotiating with a roving gang of mercenaries, the bonus points he can add to the roll of a 20-sided die – thanks to his gift of gab – can win the mercenaries’ allegiance.

The extended improvisation of players relies on the limits of their characters. When Ms Melissa Campbell, a manager of Labyrinth Games & Puzzles in Washington, DC, runs sessions for children, she explains why this tension in Dungeons & Dragons is important.

“I tell them it’s like a game of make-believe, but the rules are what actually make it fun,” she said. “If you just win all the time and defeat every monster, that is not fun.”

After two years of play-testing with the help of fans, the extremely popular fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons was released in 2014. Through intermediate reference books such as Tasha’s Cauldron Of Everything, this version of the game evolved further over the past decade to give players more flexibility.

“People wanted to be able to mix and match their species choice with their character-class choice,” Mr Crawford said. “They didn’t want choosing a dwarf to make them a lesser wizard.”

Inclusivity v authenticity

Players who are frustrated by the recent revisions argue that the innate characteristics of a species gave the game part of its allure.

“All the species are becoming humans with decorations,” lamented Mr Devin Cutler, a self-described “grognard”, or veteran gamer, who plays alongside Mr Lessard at the Boards & Brews bar in Manchester, New Hampshire.

Mr Cutler acknowledged that the game’s orcs – the malevolent, dark-skinned creatures developed by J.R.R. Tolkien – have been associated with negative racial tropes in the real world. But he said their innate traits, however fictional, have accrued authentic meaning over the decades.

Mr Devin Cutler, a long-time D&D player, lamented that “all the species are becoming humans with decorations”.

PHOTO: SIMON SIMARD/NYTIMES

In December, Mr Cutler and others gathered at a house outside Manchester for a Friendsgiving meal of turkey and sides before getting down to business: the 39th weekly session of their campaign. The fantastical characters that made up their adventuring party included a tiefling – a human-demon combination – and a human monk from the region of Shou Lung.

There was also a tabaxi, a creature with the feline appearance and night vision that one would expect of a species created by the Cat Lord.

“He’s a tabaxi adopted into an elven family,” said Mr Kyle Smith, who created the character, Uldreyin Alma Salamar Daelamin the Fifth, for this campaign. “He’s also a sorcerer – the magic is innate to that. He’s deciding between who he is and what he was raised in.”

Mr Smith added, “If being a tabaxi didn’t matter, then who cares?”

“He’d just be a fuzzy elf,” Mr Cutler chimed in.

Ms Dana Ebert, a co-founder of the gaming-centred pub TPK Brewing in Portland, Oregon, said she sensed that a majority of Dungeons & Dragons players were responding positively to the changes.

Wizards of the Coast was catching up to its competitors, said Ms Ebert, who has freelanced for Pathfinder, the role-playing game by the company Paizo that has spoken of “ancestry” and “heritage” instead of “race” for several years. As early as 2020, the independent Arcanist Press published Ancestry & Culture: An Alternative To Race In 5e, a proposal to use those words instead of “race” in Dungeons & Dragons.

Two years ago, an account called “DND staff” wrote on an official game website that new nomenclature was planned. “We understand ‘race’ is a problematic term that has had prejudiced links between real-world people and the fantasy peoples of D&D worlds,” it wrote.

Critics of the new terminology think it reflects a concession by Wizards of the Coast to changing cultural norms at the expense of authenticity to Dungeons & Dragons’ history.

Some players objected to the preface of a book about the game’s early years, published by Wizards of the Coast this year, that addressed the insensitive tropes involved in developing a role-playing game in the 1970s.

“I just don’t take those critiques seriously even now,” Mr Jason Tondro, the Dungeons & Dragons designer who wrote the preface, said in an online post. “I consider those people not worth listening to, so I didn’t anticipate their ‘outrage.’”

In response to the comment, Mr Musk posted, “How much is Hasbro?”, on his social platform, X. (Mr Musk did not respond to a request for comment about Dungeons & Dragons.)

Wizards of the Coast has pressed forward in its push towards a more inclusive game.

The company now suggests that extended Dungeons & Dragons campaigns begin with a session in which players discuss their expectations and list topics to avoid, which could include sexual assault or drug use. Dungeon masters are encouraged to establish a signal that allows players to articulate their distress with any subject matter and automatically overrule the dungeon master’s storyline.

“The signal shouldn’t trigger a debate or discussion: Thank the player for being honest about their needs, set the scene right and move on,” states the 2024 Dungeon Master’s Guide.

When Mr Kyle Mann, editor-in-chief of the right-wing satirical site The Babylon Bee, highlighted that passage online, it prompted incredulity online from Mr Musk.

Mr Kuntz said that while some topics ought to be considered off-limits, it was a mistake to interfere with the implicit social contract that has sustained Dungeons & Dragons for decades.

But Mr Akshay Arora, a software engineer and avid gamer who play-tested the new rules, defended the policy. “You’re doing something for pleasure,” Mr Arora said. “This isn’t a place you need to be forced to experience something you don’t want to go through.”

The popularity of the new rules will ultimately be determined at Dungeons & Dragons sessions, where players vote with their feet.

Mr John Stavropoulos, a user-experience professional in the healthcare industry who has consulted for Hasbro, believes that the game is headed in the right direction. For various role-playing games, he helped develop the X-Card, which lets people wordlessly touch a card to indicate their discomfort.

“When you’re playing a game, it’s like you’re in a small community,” he said. “You want the game to be as fun for one another as possible. D&D at its core says, ‘Make this game what you want it to be.’” NYTIMES