Don’t call me a motivational speaker: Why Adam Khoo has moved on to options trading

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

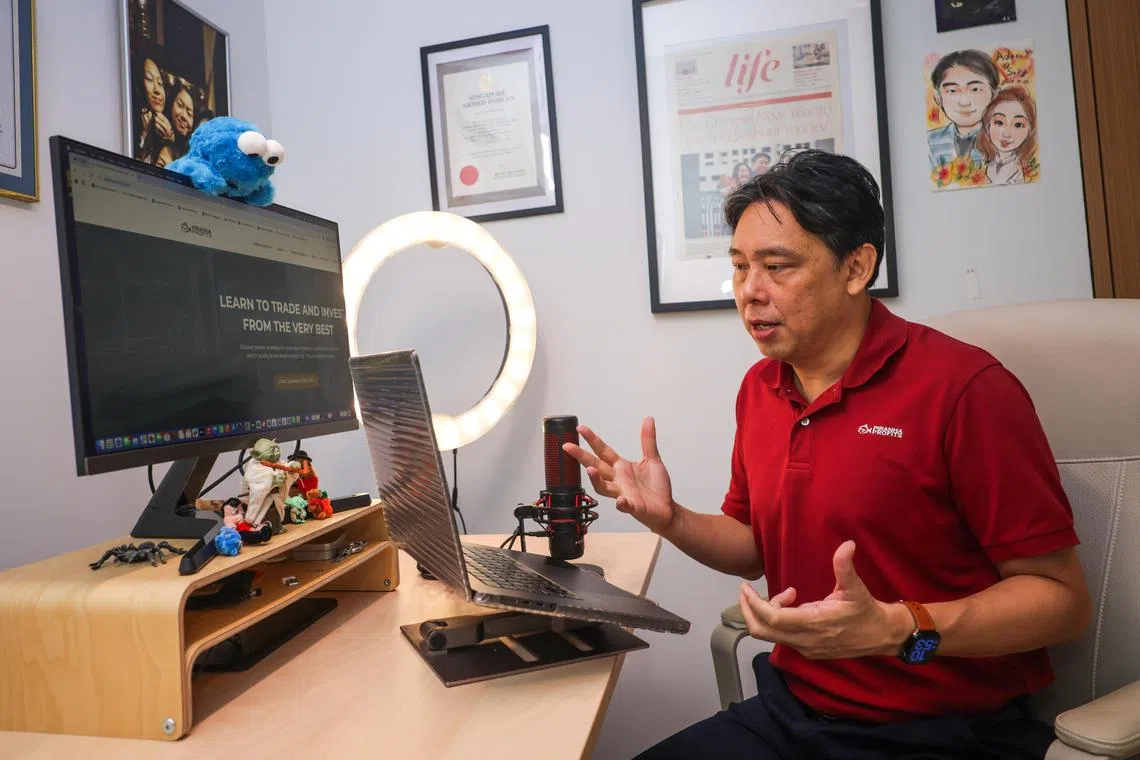

Once Singapore’s primo child-motivation guru, these days, entrepreneur and educator Adam Khoo is contented to dish out investment tips through YouTube from his home office.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Whenever the school holidays roll around, hundreds of primary and secondary school kids are dropped off at an industrial building in Eunos. They take the lift to the fifth floor, walk through a sterile, double-volume corridor, and push past a wood vinyl door, on which is hung a poster of a man.

He is dressed in a black suit and red tie, one arm akimbo, the other clasped around chopsticks holding up a post-it note, at which he gazes with steely resolve. Behind him bellow the words, mostly in capitals: IF YOU ONLY DO WHAT YOU CAN DO, YOU’LL NEVER BE BETTER THAN WHAT YOU ARE.

It is a reminder to the children that they are here to stretch their minds and excavate buried potential. That, if they try hard enough, they can also mindmap their way to a million dollars by 26, a million YouTube subscribers, a best-selling book or whatever else they desire.

That precocious millionaire, once Singapore’s primo child-motivation guru, is now a 51-year-old man who spends most of his time in a 2m by 3m room at his three-storey Siglap semi-detached house. He has reinvented himself as a value-conscious investment guru, with multiple investment portfolios worth a total of more than $22 million.

These days, Mr Adam Khoo, who is married to a pilates instructor, does not spend much time with children, apart from his daughters, who are aged 19 and 21.

No more getting up on stage to galvanise slacker kids into action. No more recounting how a five-day course transformed him, at age 13, from an indolent video-game addict barely scraping by in school to a hypermotivated overachiever with a million on his mind.

Adults are now his target audience, and YouTube is his medium of choice. He records his videos from the tiny room, unpicking the complexities of the stock market and dishing out investment tips and tricks with a $270 microphone his staff gifted him for his birthday.

His company, Adam Khoo Learning Technologies Group (AKLTG), which does youth and financial education, employs 50 staff, but his YouTube channel is a one-man show. He has produced some 600 videos that have garnered nearly 60 million overall views.

“I focus on investing because that’s what I do best,” says the self-professed loner who, for all his money smarts, never enjoyed running a business.

He stopped teaching youth 11 years ago. “It came to a stage where I was too old to teach it, that I couldn’t relate to the kids as much as I used to. They looked at me like I was some old uncle, so I realised that my trainers in their 20s and 30s could do a better job than me.”

The refresh also necessitated a rebranding.

After years of cultivating his brand, Mr Khoo wanted to scrub all invocations of his name. So, the Adam Khoo Learning Company, which used to run I Am Gifted!, started going by Aktivate Learning two years ago, while Adam Khoo Empowering Youth – the arm that ran the company’s school programmes – is known as Aktivate Education. He is still executive chairman of its holding company, AKLTG.

“What happened in the old days was everything was named after Adam Khoo. But then we realised that one day, Adam Khoo will die, then how? So, that’s the first problem: the succession, business continuity. And since I’m not involved in the youth part any more, it doesn’t make sense for it to be named after me. People will get very confused.”

He knows that his is no longer the loudest voice in the land of youth transformation. To mould young minds in 2025, one needs to wrestle through a babel of superstar tutors, life coaches and ChatGPT therapists.

Times have changed – and children, too. How has his company changed with them?

Maverick, manipulator or genius?

Depending on whom you ask, Mr Khoo is either a maverick, manipulator or genius.

Since 2003, his company has run I Am Gifted!, a programme meant to cultivate life and study skills through techniques such as goal-setting, speed-reading, emotional regulation and, most controversially, mindmapping. Such insight is imparted to students over the course of a four-day workshop. It used to be five days, but was shortened in 2023 because children “don’t have as much time any more”.

It is held at either the company’s Eunos headquarters or in schools. A team of trainers conducts quarterly follow-up sessions with attendees thereafter. It costs $2,688 a child, and attracts around 300 sign-ups a year.

Alumni of the I Am Gifted! programme are split on the efficacy of his methods.

Ms Ainur Rosyieqa, now a 30-year-old entrepreneur, recalls being asked to reckon with her “privilege” during the camp she attended as a Primary 5 pupil at Raffles Girls’ Primary School in 2006.

It made her realise how children in developing countries “would do anything to be in our shoes”, while she, a playful student who was failing mathematics and science, was taking her education for granted.

“It was this perspective that woke me up and convinced me that I needed to take the opportunities I was lucky to have and give my best in life,” she says.

Another alumnus, a 28-year-old legal associate who wanted to be known only as Ms Ye, says none of the techniques she picked up during the programme she attended in 2009 were applicable.

“I’d learnt the same things in school, and the specific mindmapping techniques they taught were a poor one-size-fits-all approach. It felt a bit like whacking everything but the kitchen sink in the hope that something would stick.”

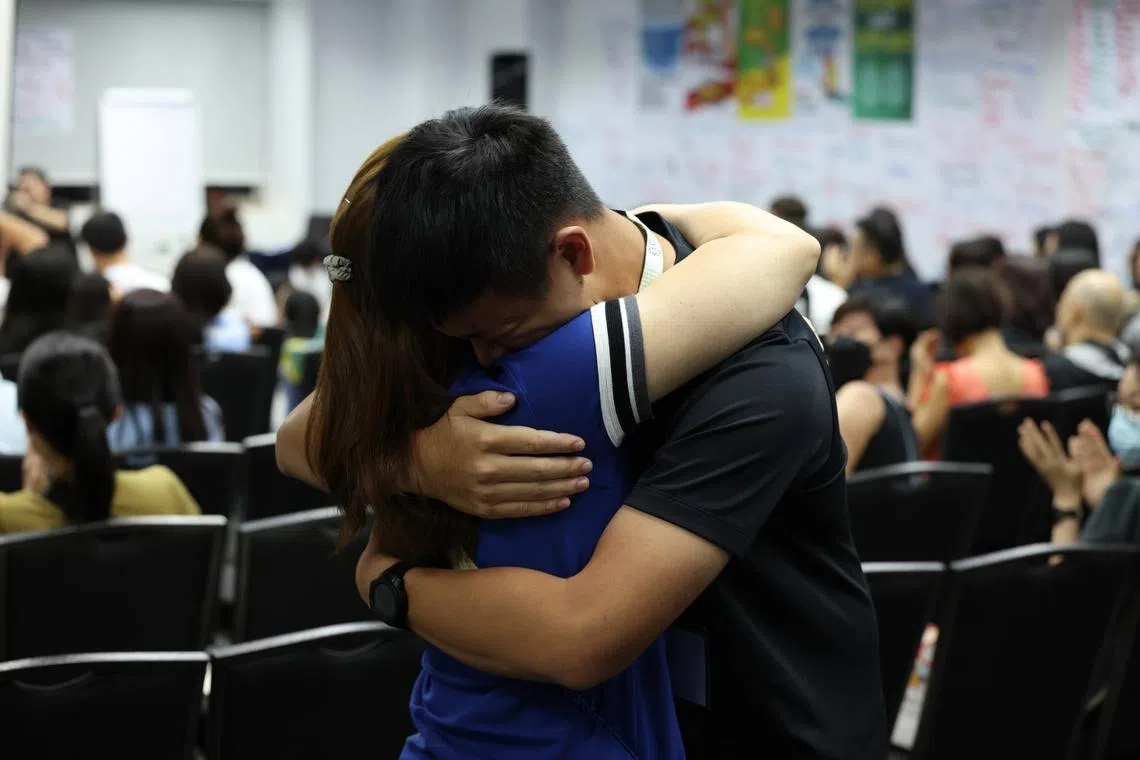

A student embracing his parent during an I Am Gifted! camp.

PHOTO: AKTIVATE LEARNING

Some level more serious accusations at the programme, notorious for its emotional intensity. Students have been asked to visualise the death of their parents and then channel the resulting fear into productive energy.

One former student, who spoke on condition of anonymity, recalls attending a programme in the lead-up to her O levels in 2011. “I don’t recall the exact questions they’d asked, but they managed to get people to trust them and open up in front of everyone. A girl stood up and shared about how her dad had passed away, and there was a lot of crying in general. The questions seemed to be aimed at making people cry.”

Though it worked to an extent – “I’d never been as motivated as I was for O levels” – she was left with a lingering sense of unease.

A journal entry from the period records her discomfort with the way trainers referred to the second day of the programme as “confession day”.

She started to wonder if the trainers, whom she had come to respect, were feigning vulnerability to get the students to open up. “It felt cult-like and emotionally manipulative, to get a bunch of teenage girls to trust them and guilt-trip them,” says the now 29-year-old administrator.

Mr Khoo, however, maintains that the courses were deliberately designed to be emotionally intensive. He says: “Ultimately, people change only when there’s enough pain. So, I always say, do we want to wait for the real pain to happen or do you want to create that impetus in your mind first?”

After all, it worked on him. His mentor from Super-Teen Camp at Ladyhill Hotel in 1987 told the Ping Yi Secondary School boy to visualise what might happen if he continued down his path of insouciance.

The exercise triggered a montage of horrors – disappointed parents, constant struggles – that shocked him into studiousness.

But he says the programme he went on to devise upon his graduation from NUS Business School has bigger ambitions. In addition to lighting a fire under participants, it also takes it upon itself to mend their broken relationships.

Parents are invited to the graduation ceremony, during which children take turns to share what they learnt at the course and thank their parents. “And I can tell you, at every session, there’s not a dry eye. We’ve had cases in which a daughter, who hasn’t spoken to her dad for two years, tells him she loves him for the first time. It’s very powerful,” recalls Mr Khoo.

Not everyone shares his sentiment, however.

Mr Lee, a 22-year-old university student who gave only his last name, wishes this reconciliation could have been handled with greater sensitivity in his case. During the programme, which he attended some 13 years ago, students were asked to give their parents a big hug and tell them “I love you”.

Mr Lee, who had a chaotic home life and a tenuous relationship with both parents, could not bear to utter those words. To his mortification, he was called out for his reticence in front of his peers.

“I felt very humiliated. It made me feel very lousy, like I was a bad son who was very ungrateful,” he says, calling such behaviour “totally unacceptable, as it fails to let people heal and mend their relationships in a natural and more conducive manner”.

Dialling down emotional intensity

A trainer speaking to students at a I Am Gifted! camp.

PHOTO: AKTIVATE LEARNING

On the whole, Mr Eugene Pan, the 46-year-old deputy group director of Aktivate Learning and Aktivate Education, says his team has dialled down the emotional intensity of their programmes.

The extra workshops it conducts for 90 or so primary and secondary schools each year, for instance, focus on nurturing life-long learners with future-ready skills like digital literacy and marketing know-how, in line with the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) goal to untether learning from the classroom.

In response to questions from The Straits Times on hiring external vendors, the ministry says schools “have the autonomy to assess and engage external service providers to conduct enrichment programmes and workshops for their students, based on their specific needs”.

They work within the ministry’s guidelines to ensure appropriate instructor conduct, as well as relevant and respectful content.

For example, Mr Pan says primary and secondary school students who attend Aktivate Education’s camps in MOE schools are no longer asked to imagine life without their parents.

This exercise, however, remains part of the I Am Gifted! workshops open to the public, but staff say such sessions are handled with care.

Charles Tan, 17, a first-year junior college student and I Am Gifted! alumnus who attended the five-day camp in 2021, notes that the camp is constantly evolving to keep pace with shifting sensitivities and learning habits. For instance, a lesson on speed-reading has been replaced with guidance on how to look for resources online, as technology becomes more entwined with education.

A former segment called Total Truth Process, in which coaches give participants feedback on their behaviour, has been phased out in favour of a less confronting social circle activity, where everyone gets the chance to speak and self-reflection is nudged along in a gentler way.

The I Am Gifted! flagship programme is also restricted to those above the age of 10, when in the past, it used to accept lower-primary pupils. This, Mr Tan hopes, means participants will be equipped with more emotional maturity to grapple with hypotheticals, such as losing their parents, that are meant to help them develop perspective and empathy.

“They need to be at the age to understand these kinds of realities. It’s not that we’re threatening them, but let’s face it, no one’s living forever. So, we just want to encourage them to appreciate their parents while they’re around.”

Why these camps remain popular

Since its inception in 2003, the company estimates that the school and public camps run by Mr Khoo and his team have reached more than 580,000 students across South-east Asia. It says it trains some 25,000 students annually through school talks, workshops and public programmes.

Its content is rooted in part in neuro-linguistic programming (NLP), a psychological approach that explores how language and thought can affect behaviour, which some researchers have denounced as pseudoscience.

Mr Khoo, however, stands firmly behind this school of thought. “To me, the most important question is does it work? I teach only things that work. The funny thing is that I studied finance in NUS and can tell you that 90 per cent of what you learn in academic finance doesn’t apply to the real world.”

Students at a I Am Gifted! camp.

PHOTO: AKTIVATE LEARNING

Dr Caroline Koh, associate professor with psychology and child and human development at the National Institute of Education (NIE), notes that while NLP tools could help boost self-esteem if wielded by someone with the relevant expertise and knowledge, they could have the converse effect when deployed arbitrarily.

“NLP techniques would be more effective when administered to single individuals or small groups rather than mass-administered to large numbers of participants,” she says, stressing that trainers need to be able to gauge when a particular technique might be appropriate.

These trainers, in Aktivate’s case, are four full-time staff with over a decade of experience in conducting workshops for youth. They were trained by Mr Khoo and now helm the programme with the help of 60 or so coaches, mainly I Am Gifted! graduates aged between 13 and 28 who passed a rigorous selection process.

It is this human guidance, plus the ability to adapt to the differing needs of new generations, that Mr Pan hopes will keep Aktivate relevant, in a world where advice can be sought with a simple prompt on ChatGPT.

In line with the preferences of younger cohorts, camps now weave in teamwork and games. In one titled the Game Of Life, students get a foretaste of the future by racking up happiness points through education, work and money.

In some ways, this sort of big-picture thinking can help foster intrinsic motivation, especially among older students, says Dr Gregory Liem, an associate professor at NIE’s psychology and child and human development academic group.

“Sometimes, students are not able to identify the relevance of schooling – why they need to study certain subjects. If they want a comfortable lifestyle, if they want money, they’ll need to do a certain kind of work, study certain subjects. So, it helps to have a plan,” he adds.

Besides, he says, as long as there are “kiasu” parents, there will be “kiasu” programmes.

Money and meaning

Mr Adam Khoo, who garnered attention for being a self-made millionaire at 26, says that education, not business, has always been his passion.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Money may still be on Mr Khoo’s mind – he is, after all, in the business of dispensing financial advice – but it is no longer his priority. Family No. 1, work No. 2, so his mantra goes.

Interestingly enough, despite all the fire and brimstone, despite all those years spent whipping other people’s children into shape, he is no tiger parent at home.

“I’m proud to say that my wife and I are quite easy-going. We don’t spoil them, but we teach them through games like Monopoly,” he says.

Both his daughters, currently in university, went through his motivational boot camp and enjoyed it so much, they returned as coaches. And, yes, they had to visualise his death too.

Whether they take over the business in the future is up to them. He is contented with the work he has done and the way in which he has done it. He fields questions with practised ease, pausing only to consider if he has any regrets. (Just one: not taking his Chinese lessons seriously.)

Brickbats do not bother him, unless they come from people who attended his programmes.

All that matters is that he is remembered, so he hopes, as someone who has helped “millions of people around the world discover their potential and live life in the fullest way possible”.