Doc Talk: Saving lives through cancer screening is more complicated than you think

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Cancer screening will feature prominently in HealthierSG's strategy roll-out.

PHOTO: PEXELS

Wong Seng Weng

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Singapore has a new national health strategy: HealthierSG.

It is the new policy roadmap to, someday, delivering a heathier population.

Of the many planks in the HealthierSG platform , health screening

Since cancer is the No. 1 cause of death in Singapore, it follows that cancer screening will feature prominently in the strategy roll-out.

The logic of cancer screening is both simple and fairly compelling.

The diagnosis of cancer is not always a death sentence. Many forms of cancer can be permanently cured, if discovered in the early stages.

Certain tumours can be detected in the pre-cancerous stage, cancer of the cervix being an example.

Early treatment with better outcomes will improve longevity, reduce the burden of care on the patient’s family members, prevent a society from losing years of productive life in its population and conserve healthcare resources.

So far so good.

So, if a national cancer-screening programme is comprehensively rolled out and gains wide acceptance by everyone, would it then be the sword that finally slays the monster that is cancer? No.

Why not? What are the inherent weaknesses of cancer screening? Is there genuine value in this strategy? Most importantly, what should your attitude, as a “consumer”, be towards cancer screening?

The bottom line: Do embrace cancer screening as your personal health strategy, but be realistic about the pros and cons. And, yes, avoid the potential traps, of which there are several.

Truly helpful cancer-screening tests have many boxes to check.

First, not all cancers can be, or even should be, screened for.

The types of cancer that people screen for have to be “significant” – significant in frequency of occurrence and significant in terms of mortality. Screening for uncommon cancers would not be sensible if people examine the balance between a few people gaining from earlier diagnosis of their cancers, and the cost and inconvenience of a huge population going through unnecessary medical investigations.

Breast cancer is the most common female cancer in Singapore and therefore merits population-wide screening. Cancer of the pancreas, on the other hand, is deadly but not common enough in the population to justify routine screening.

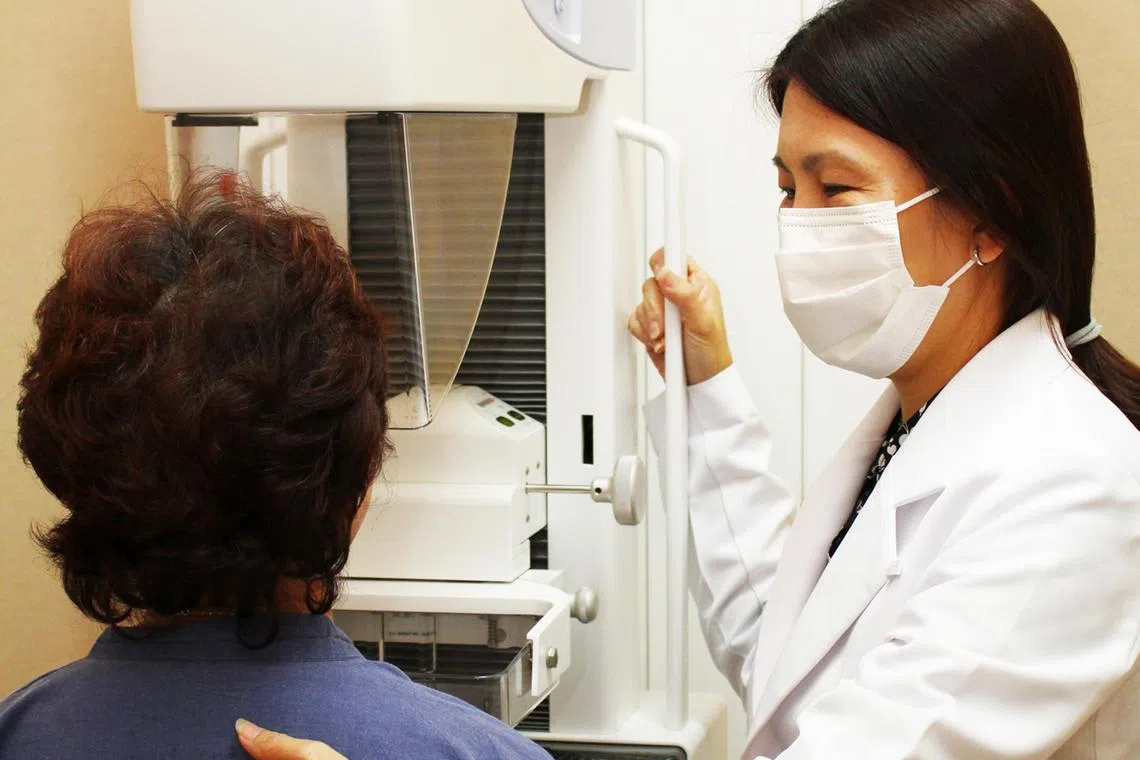

A woman undergoing a mammogram screening.

PHOTO: SINGAPORE CANCER SOCIETY

Cancers that people screen for need to be easily recognisable at the early stages and the duration of development must be sufficiently long to give fair opportunity to pick up the disease, before it progresses to the late stage.

For instance, screening for colon cancer is more feasible compared with gastric cancer, as early-stage colon cancer is easier to recognise than early-stage gastric cancer through endoscopy.

Cancer of the cervix takes years to complete the pre-cancerous stage of development, giving ample time for screening to pick it up. Good candidate for cancer screening.

The screening test has to be safe. Medical investigations sometimes carry risks, such as radiation exposure. The downsides cannot be too prominent, otherwise we end up injuring or harming too many people without cancer in the process.

The screening test has to be quite precise.

There isn’t a perfectly precise cancer-screening test. All these tests carry a certain false-positive and false-negative rate. When a test signals a problem even though the cancer being screened for is not present, that is a false-positive. In other words, a false alarm. When a test signals that the coast is clear, but a cancer is actually present, that is a false-negative – a false reassurance.

Screening tests with very high false-positive and/or false-negative rates do not make the cut. Many blood tests measuring cancer markers in the plasma land in this space and are hence not recommended as a cancer screening tool by national health authorities.

The anxiety associated with false-positive cancer screening tests can be a heavy price to pay.

The screening test has to be validated in large-scale clinical trials to demonstrate that, on average, it improves people’s likelihood of survival.

Do not fall for screening tests that have only skimpy and preliminary scientific data. These tests may sound promising in theory, but are not backed up by sufficiently robust clinical-trial data. Many screening tests looking for cancer-associated genes fall into this category at present.

The widespread application of cancer-gene testing to guide cancer treatment decisions should not be confused with the suitability of such a technique to screen for cancer. Genetic information picked up by such tests may have implications on people’s lives beyond just cancer detection and open a Pandora’s box.

The cancer being screened for must have a better treatment outcome if treatment is instituted earlier rather than later. This is not a given.

The reason that screening for prostate cancer is controversial to this day is that many slow-growing prostate cancers occur in elderly men with many other medical comorbid conditions that limit their longevity.

Detecting slow-growing prostate cancers and giving early treatment to these folks with all the associated treatment side effects are, hence, unlikely to bring much benefit since prostate cancer may ultimately not be the cause of death.

It must be apparent by now that a decision on whether to undergo a cancer-screening test requires careful consideration of the delicate balance between benefits and risks, not to mention costs.

To accept that all cancer-screening tests in existence are an unmitigated good would be naive. To reject all such tests as potentially doing more harm than good would be to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

A good cancer-screening strategy requires commitment by the patient, as the screening test usually has to be repeated at pre-determined intervals over many years. There can be no commitment without proper understanding. In fact, muddling through the decision to undergo certain cancer-screening tests often leads to “buyer’s regret” in the end.

Is the detection of a particular cancer worth the effort to undergo screening? Is the test precise and safe? Is it backed by robust clinical trials and would earlier treatment produce better results?

Have that conversation with your doctor.

Dr Wong Seng Weng is the medical director and consultant medical oncologist at The Cancer Centre.