Do Singapore’s Gen Zs still know how to party?

Sign up now: Get tips on how to grow your career and money

Marquee's FTW themed night courts new blood with free entry and freeflow drinks.

PHOTO: MARQUEE SINGAPORE

- Nightlife operators are courting Gen Z partygoers with aggressive cost-cutting, in a competition that increasingly plays out over social media platforms like Telegram.

- Despite rave reviews, partygoers and operators question the sustainability of the trend towards sobriety and wellness in Singapore's party culture.

- No longer a universal rite of passage or a primary way to meet new peers, party culture increasingly occupies a more niche and subcultural space among youth.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – Step into Marina Bay Sands’ Marquee nightclub on a Wednesday night, and one finds a curious answer to the question: Do Gen Zs still know how to party?

Tourists and expatriates are in the minority here. Instead, the venue is packed with young adults in their early 20s, complete with long queues for the indoor ferris wheel and screaming glee as the nightclub drops a blanket of balloons on the dance floor.

But, behind this glittering facade, the establishment has been working overtime to court new blood.

This particular party is one of Marquee’s FTW themed nights, when the nightclub opens an hour earlier at 9pm, offering complimentary admission and free-flow drinks until midnight for a limited number of partygoers. Marquee’s typical maximum capacity is just under 2,000 people.

It is part of a strategy that includes $40 student discounts on “infinite pour” drink promotions, exit vouchers for free entry the following week and e-mails enticing past patrons to come down with guests for free.

This strategy pays off in volume. Marquee has seen month-on-month growth in patronage since January, says Mr Patrick Robertson, Marina Bay Sands’ director of nightlife operations.

“At the start of this year, we noticed a shift in partying trends within Singapore’s nightlife scene, which prompted us to refine our operations,” he says.

“With a larger Gen Z crowd today, the key difference in the industry is the pace of change. Nightlife trends used to shift every two to three years, but we now see them evolving every few months.”

Even as liquor licensing hours were recently extended till 4am in limited parts of Singapore

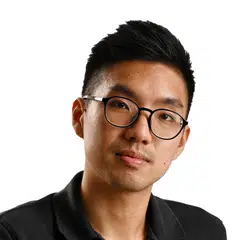

Underground party collective Thugshop has begun hosting Higher Sundays events with $1 cover charges and cheaper drinks, while offering free drinks and waiving cover charges through its Telegram channel.

Nightclub Zouk, too, has been wooing the young adult crowd with promotions at its Redtail bar, while blasting its over 12,000 fans on Telegram with promotions alongside Gen Z-infused meme culture.

Such measures reveal a fundamental shift: Gen Zs will party, but only if the barriers are lowered – a trend that has some operators worrying about sustainability.

Mr Kavan Spruyt, founder of nightclub and event space Rasa, points to aggressive cost-cutting as a sign of the “kind of sacrifice that operators now need to make in order for crowds to come in”.

“What’s separating the clubs that have vibrancy versus the ones that don’t is the ability to invest a lot of money,” he says. “Why are we offering free entry? Because people can’t afford it otherwise.”

The 44-year-old had his first brushes with Singapore’s party culture in the 1990s and 2000s, which he says felt like a different economic reality.

“Back then, if I had $50, I could go out, share a jug with my friends,” he recalls. “If I had $80, I could get a little bit wasted. Now, $80 is only going to get you cab fare.”

Shorter attention spans, higher expectations

As more Gen Zs come of age and enter the scene, the biggest changes in party culture are not just economic.

“Their attention span is shorter, so you have to grab them really quick,” says Ms Sheryl Sho, 28, resident DJ at Thugshop.

“With the younger crowd, you can see when they start to fade away when a track has gone on a bit too long, and you have to transition faster to get them back.”

This extends beyond music.

In today’s attention economy, party collectives compete for eyeballs on platforms like Telegram and Instagram.

PHOTOS: TELEGRAM

For extremely online Gen Zs like Mr Sim, a 27-year-old draughtsman who declined to share his first name, gone are the days of partygoers going to the same established venues every weekend.

Instead, Gen Zs pay attention to Telegram channels and the social media accounts of party collectives like Culture, which curates events catering to what Gen Zs want.

As social media is a key shaper of what a good time looks like, parties have increasingly become fodder for businesses’ TikTok and Instagram accounts. Checking an establishment’s Instagram story is one way consumers discern whether it has a lively enough vibe to merit a visit.

“We speak to Gen Zs in their own digital spaces,” says Ms Christine Tan, Zouk’s brand and marketing manager. “Our Telegram channel, for example, has a completely different tone and vibe from our other platforms.”

Gen Z partygoers packed into Funan mall on Aug 29 for a two-night-only sober party.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

The most visible expression of this comes from the smash success of coffee clubbing collective Beans&Beats’ takeover of Funan mall

“Can a group of 20-year-olds take over an entire shopping mall to throw a sober youth music festival?” one member of the collective asks in a TikTok clip that drew more than 300,000 views on the platform.

“For the past month, we spent sleepless nights planning something that has never been attempted in Singapore.”

The result of that campaign was more than 5,000 partygoers cramming into Funan’s basement foodcourt and two other party zones upstairs from 10pm to 1am.

Peeling back the curtain and getting up close with party organisers has long been a hallmark of content created by Gen Z collectives, which have used social media to identify niches and build communities at unprecedented speed.

Beans&Beats co-founder Aiden Low says that when the team produces TikTok videos or Instagram reels, revellers love to get in front of the camera and become part of the collective’s content. “Social media has impacted how we think of parties.”

Singapore party culture is increasingly inseparable from social media algorithms and aesthetics.

PHOTO: BEANS&BEATS

This sober party collective began as a friends-and-family gathering that its trio of then-20-year-old founders recorded and posted online in 2024.

“People were reaching out saying, ‘this is so cool, where is this happening?’” Mr Low recalls. That initial virality inspired them to launch their first public party of over 100 attendees at Pearl’s Hill Terrace.

Their main selling point: trading booze for coffee in daytime or earlier-evening sober parties – avoiding hefty alcohol bills and late-night transportation costs, while creating more mindful crowds bonding over shared interests rather than liquid courage.

“Because you’re not intoxicated, you’re able to enjoy the music as it truly is,” Mr Low says.

The “pickier” generation

Singapore’s “biggest sober party” had Gen Zs filling up a basement foodcourt, a sportswear store and Mexican chain restaurant Guzman y Gomez.

PHOTO: BEANS&BEATS

Many young adults now feel priced out

At the growing number of “sober raves” across Singapore, many partygoers speaking to ST described themselves as “retired clubgoers” despite being in their early to mid-20s.

Business owners and Gen Z Singaporeans also say the post-millennial generation prefers events that start and end earlier (to avoid steep last-night transportation fees), a trend that is fuelling the rise of “daylife” and earlier-evening parties.

They are also more sensitive to cost pressures than older generations were at their age. While promotions and happy hours have always existed in the nightlife sector, Gen Z’s entry into the party scene has meant a growing reliance on cost-cutting to fill venues.

At this Beans&Beats party in Bugis, everyone is sober.

ST PHOTO: JASON QUAH

Beans&Beats co-founder Mateo Lie, 21, believes that for young adults of previous generations, not going out on a Friday night was once seen as “sacrilegious” – a norm the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted.

Now, faced with an ever-expanding array of options for Gen Z and cost pressures, Singapore’s youngest generation of partygoers are “pickier” than ever, he says.

Gone are the days when establishments could rely on reputation alone for steady footfall. Singapore’s major nightlife venues now release a steady stream of future line-ups, packed with headliners and themed nights, on their social media.

“You cannot just have a very standard line-up, with no story behind it and just call it ‘Club Night’,” says Mr Lie. “They want a theme. They want to feel like they’re a part of something. So, we have to programme at a higher level.”

Not your father’s party

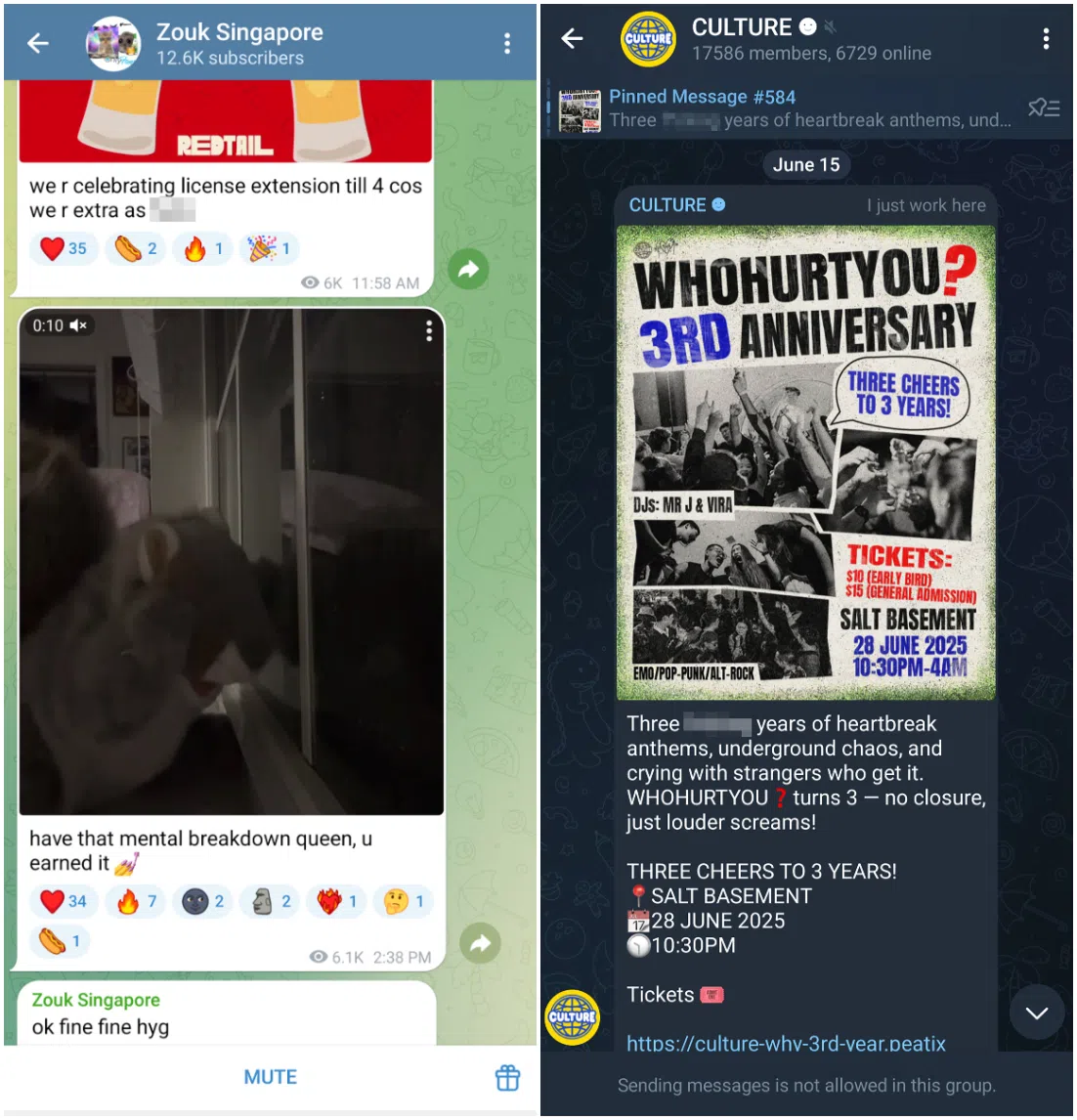

Gen Z-founded music collective Exposure Therapy’s parties blur the lines between wellness and clubbing.

PHOTO: EXPOSURE THERAPY

Beans&Beats is just one of many post-pandemic Gen Z party collectives

Gen Z collectives 5210PM – known for organising parties that end by 10pm – and Exposure Therapy are seizing upon their generation’s interest in daylife and wellness.

Exposure Therapy organises “matcha raves” and other events that blur the lines between partying and wellness, like pilates with an afterparty.

While Beans&Beats prefers sunlight and cafes, Exposure Therapy takes over nightclubs, as its team believes lighting and shutting out the outside world are key for setting the mood.

Part of the appeal of this new strand of Gen Z parties is their inclusive vibe and more intentional atmosphere.

PHOTO: EXPOSURE THERAPY

Co-founder Harpreet Gill, 23, sees it as something distinct from the party culture that came before: “There was a chance to integrate both nightlife and wellness, and create a third space. Our intention was not to take over something, but to create something new.”

Unlike nightclubs, where people stream in later so they can arrive when the crowd is buzzed and the party is in full swing, those attending sober parties arrive fresh and early – and need warming up.

Mr Shahan Shah Shawn, the collective’s 24-year-old DJ, says this means planning music that blends the new with the comfortable, such as recognisable vocals with an unconventional bass.

He, too, believes a different kind of socialisation emerges at these parties, where people bond over shared interests and, at times, the awkwardness of being mashed together in a packed venue – rather than alcohol-fuelled flirting and unintentional stumbles.

Sober by choice?

Marquee’s FTW themed nights are a hit with Singapore’s youngest generation of partygoers.

PHOTO: MARQUEE SINGAPORE

Not everyone is convinced the trend towards sobriety and wellness is here to stay.

Many Gen Zs speaking to ST say they occupy a space distinct from party culture as most understand it.

“The people who attend daytime or sober events usually don’t go for nightlife events in the first place,” says Mr Sim.

The overall prevalence of binge drinking has stayed the same from 2019 to 2023, according to the Ministry of Health’s most recent annual national population health survey.

Data from elsewhere indicates that proclamations of Gen Z’s declining interest in drinks may be overstated.

In June, drinks industry intelligence firm IWSR published an analysis which found that in the world’s 15 leading markets, Gen Z interest in alcohol is making a comeback, even as budgets for alcohol shrink due to the high cost of living and a broader trend towards moderation.

“I’d love to be drunk, trust me,” says Ms Minh Tan, a 24-year-old student who adds that her sobriety is by necessity, not by choice. Her nights out to venues like Marquee involve no alcohol beyond the free drink that comes with her ticket. “The music is enough adrenaline.”

“I’ve never lived in a world with the NightRider bus,” she adds, “but its reintroduction would make me consider having more nights out.”

The after-hours NightRider bus service, introduced in 2000, previously operated between 11.30pm and 2am before it was discontinued in 2022.

Aesthetics versus culture

Underground music collective Sivilian Affairs says Gen Zs make up a small but sizeable contingent at its parties.

PHOTO: SIVILIAN AFFAIRS

Among those who have been part of the scene longer, there is a sense that the shift towards moderation and wellness might be diluting something essential.

“Some people view it as an aesthetic in itself rather than as a culture,” says a nightlife operator with over a decade of experience in the sector who declined to be named, referring to the new parties appealing to the health-conscious crowd. “I think that’s why it’s a lot easier for them to pick up, because it’s trendy.

“A lot of people nowadays are about wellness and staying healthy, but they stay home so much, so it’s not a balanced life. That’s where all of these other ‘rave-adjacent’ things come in. They’re chasing this aesthetic where you party, but also go to the gym in the morning.”

This culture clash is compounded by how the pandemic not only created a rupture in the youth-to-partygoer pipeline, but also in how party culture gets transmitted, says Ms Lilian Hautemulle, 41, one half of the Singapore-based husband-and-wife DJ collective Sivilian Affairs.

The increasing affordability of audio equipment, the rise of social media and the growing receptiveness of venues to working with new players has meant that the barrier to entry for collectives and DJs has fallen.

“A lot of these new ‘Covid DJs’ were not well connected with establishment platforms and thought, let’s start our own parties,” she says, referring to those who, like her, picked up DJing during the pandemic.

Ms Hautemulle, like many other organisers and operators, has mixed feelings about the sector’s broader shift towards lifestyle experiences.

“The terminologies of these new lifestyle parties can be frustrating,” she adds, noting that the word “rave”, for instance, has a distinct meaning in Europe, where it is associated with underground music and an alternative vibe.

A risky gamble

Despite rave reviews, partygoers have expressed scepticism that “the biggest sober party in Singapore” can be easily replicated.

PHOTO: BEANS&BEATS

There is also the issue of sustainability.

Alcohol sales have long been a core revenue stream for nightlife operators. The shift away from it is a gamble that might not be sustainable for all operators, and especially venues with higher overhead costs.

The Beans&Beats party at Funan, for instance, was part of a Gen Z friendship festival organised by youth organisation For Real Co, with support from the Ministry of Social and Family Development.

Attendee Mr James, a 26-year-old tech worker who declined to share his last name, remarked that many at the event were there because of the lack of an entry fee.

“In the long run, if you want to do this for free, it’s not easy,” he adds, expressing scepticism over whether such events have longevity in Singapore.

But Ms Hautemulle says: “I think it’s important to embrace new directions that you see in nightlife. You can’t be stagnant. What is the appeal here, why is it working?

“It’s exciting to see boundaries being pushed. We don’t want to completely redefine ourselves, but we are willing to try new things.”

And it is not just Gen Zs who enjoy earlier evenings, she notes.

For Sivilian Affairs, earlier-evening parties have been a hit with young parents and those who appreciate a set that ends early enough for them to get a good night’s sleep.

Ice Cream Sundays’ parties start and end early.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

Ice Cream Sundays is one party collective that was early to the daylife trend. It is celebrating its ninth anniversary in September.

Co-founder Daniel O’Connor, 33, believes changes in Singapore’s party culture do not stem only from Gen Z, but also from how consumers in general have become more selective about the parties they attend.

More recently, the collective has expanded its offerings with more alcohol-free options and partnerships with groups like the Aliwal Chess Club so that partygoers can take a break from the dance floor with a game of chess.

Mr O’Connor notes that such offerings are essential for a diverse clientele, but that it is also important to be a party “first and foremost”, rather than a festival with “tons of programming”.

“Day parties and pop-up events may be more ‘in’ than ever right now, but these things are cyclical, and they don’t diminish the relevance or importance of other nightlife formats, now or in the future,” he adds.

“You need all of these facets of the industry to co-exist and thrive in order to have a truly healthy music scene, in our opinion.”

From youth culture to subculture

A Lorde album launch party at Rasa in July shows that Gen Zs still crave the beat.

PHOTO: RASA

Perhaps the most fundamental shift is how partying occupies a different place of importance among Gen Z’s priorities – no longer as a universal rite of passage, but as something increasingly niche and subcultural.

Rasa’s Mr Spruyt observes that nightlife is no longer the primary or only way for young adults to meet and socialise with peers of their own age.

His more than two decades of experience in the nightlife sector include stints in local establishments Zouk and The Vault, as well as legendary Berlin nightclub Berghain.

In his view, the rise of social media, the pandemic-driven changes to remote work, the dwindling affordability of late-night options and changing cultural norms have come together to create an environment where those looking to date or make new friends turn to apps or sober activities instead.

“When I met my wife, it was through going out, not using apps based on preferences,” he says. “Going out is now more intentional, as opposed to back then, when going out was a chance to meet new people.”

This means a tougher environment for operators, who need to work harder than ever to prove their value to an increasingly sceptical audience.

The scepticism extends even to alcohol suppliers, Mr Spruyt adds, noting that they are now more likely to “wait and see” before dipping into their advertising and promotion funds for new venues.

“It’s very different from what I experienced pre-Covid,” he says. “It’s an uphill process.”

Rasa co-founder Kavan Spruyt believes that a revival of youth party culture is on the horizon.

PHOTO: RASA

Many Gen Z partygoers speaking to ST describe partying increasingly as an activity for devotees of music and dance, rather than something with mass appeal. In this new culture, only those tuned in to the right channels stay “in the know”.

“In any country outside Singapore, it’s okay to be in your late 20s and 30s partying,” says management consultant Hayden Chen, a 24-year-old former bartender.

Here, however, it is a common refrain to hear one’s peers go: “Aren’t you too old to be out clubbing?”

It does not help that cost pressures mean a growing economic divide – between those who can afford to party hard and those who cannot.

“Being 24 and going into a club without bottle service, you’re intentionally made to feel out of place,” says Mr Chen.

Still, Mr Spruyt believes there is cause for optimism, especially now that a new generation of partygoers is getting its first taste of late-night revelry.

Recent events at his venue Rasa – such as an album launch party in collaboration with Universal Music Singapore for New Zealand singer-songwriter Lorde in July – saw the place packed with Gen Zs.

Alas, that enthusiasm was undercut by many leaving well before the club’s 3am closing time to avoid the late-night surge in Grab fares.

For his part, Mr Spruyt is firm in his belief that Gen Zs do know how to party.

“Gen Zs can and will go out if there’s a reason to,” he says. “The main issue is that it’s becoming unaffordable and not sustainable at all.”