Batik Nyonyas exhibition showcases artistry in diversity

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Batik Nyonyas: Three Generations Of Art And Entrepreneurship follows the lives and careers of three Indonesian batik-makers as their business evolves, led by the women of the Oeij family.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

SINGAPORE – The Peranakan Museum’s latest exhibition, which presents about 200 heirloom batik textiles and accompanying objects such as accessories, zooms in on three Chinese Peranakan women from the northern Javanese port city of Pekalongan who helped shape batik-making in Indonesia.

The showcase, Batik Nyonyas: Three Generations Of Art And Entrepreneurship, ends on Aug 31. It invites visitors to explore the interwoven stories of family, creativity and business acumen.

What makes the contributions of Nonya Oeij Soen King, her daughter-in-law Nonya Oeij Kok Sing and her granddaughter Jane Hendromartono stand out is that each artist navigated political, cultural and economic challenges from the 1890s to the 1980s to stay focused on one thing: innovations in batik design.

Batik is a Javanese term that refers to the technique of creating patterns on cloth by drawing or stamping with a wax-resist process before dyeing.

The wax can be applied as a drawing with a canting (pronounced “chanting”) or batik pen, or as a repeat pattern stamped with a copper block called cap (pronounced “chahp”).

The showcase Batik Nyonyas: Three Generations Of Art And Entrepreneurship ends on Aug 31.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Peranakan historian and author Peter Lee says batik has been in existence for centuries. The earliest examples – found in the Taman Peninsula near the Black Sea in the fourth century BCE, and in Niya, Xinjiang, in the second century CE – exhibit Hellenistic influences.

Many examples of Chinese Tang Dynasty batik were found in Dunhuang, as well as Chinese and Japanese versions in the Shoso-in Imperial Treasury dating from the eighth to 10th centuries.

Around the 19th century CE, Javanese batik became the source of inspiration for versions made in Europe and South-east Asia.

Dyeing to innovate

Mr Lee – who is also the co-curator and lead researcher of Batik Nyonyas – worked closely with a team of curators from the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) and Peranakan Museum, as well as scholars, donors and designers, to bring the exhibition to life.

The exhibition was made possible through the collective donations of 100 batik pieces from the daughters of Jane Hendromartono – Ms Ika, Ms Melia and Ms Inge Hendromartono – as well as the family of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee, and batik collector Agam Riadi.

Batik Nyonyas exhibition co-curator Naomi Wang at the Curator’s Tour event in November 2024.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

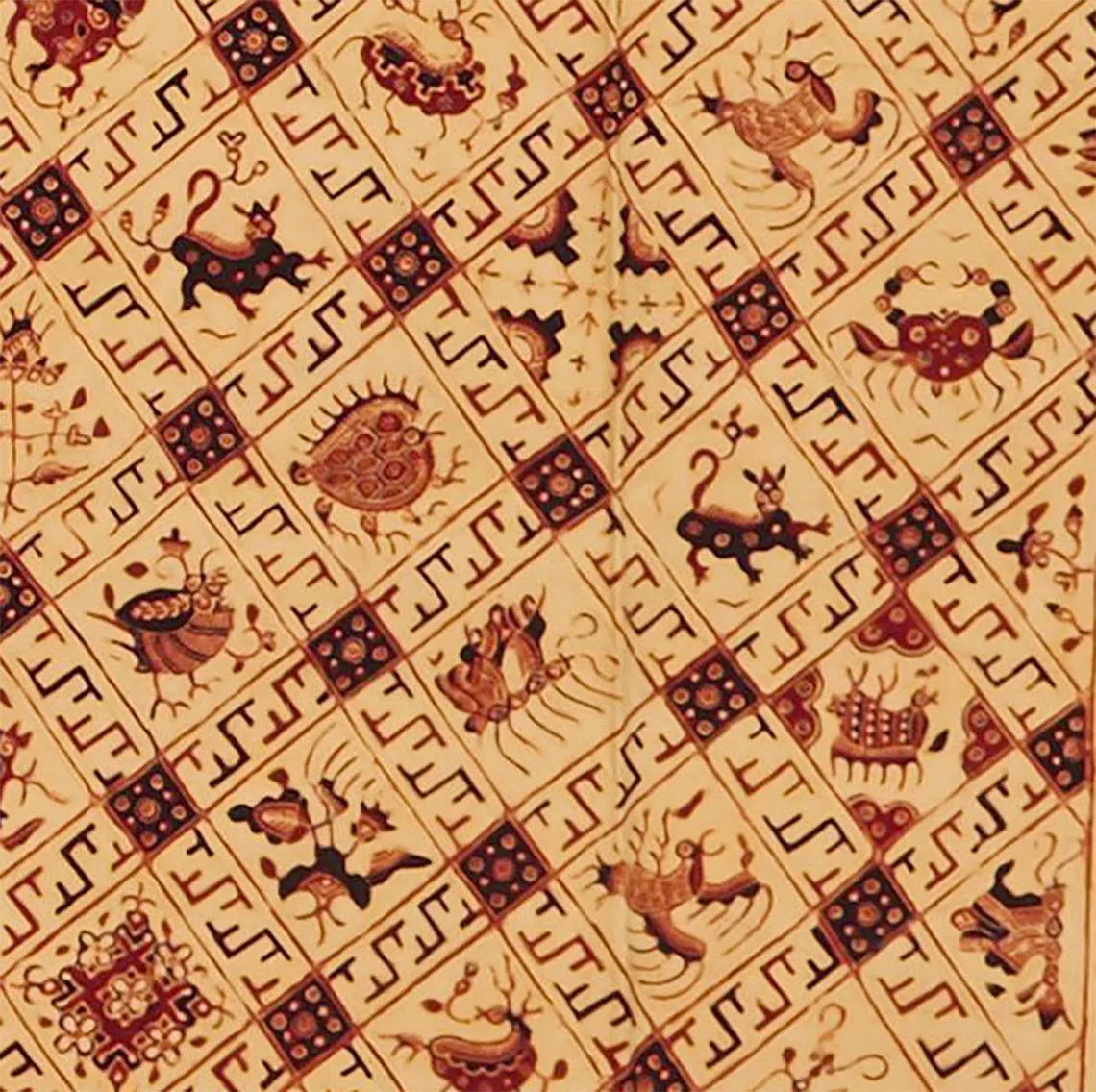

Mr Lee says Nonya Oeij Soen King (1871 to 1950) worked mainly within the vocabulary of an older style and used a variety of natural dyes, at a time when many batik-makers were shifting towards more modern influences and materials.

The importance she attached to negative or unpatterned space in the batik canvas was exceptional, he says. It was extremely technically challenging to create flawless undyed backgrounds without any of the hairline breaks or craquelure of wax in the dye-resist process.

“All her works have pristine backgrounds, a major feat considering that the fabric was subject to intense handling over 30 days of repeated dyeing, rinsing and drying – necessary to obtain a deep red from mengkudu root,” says Mr Lee.

Mengkudu root from the Morinda citrifolia tree was used for centuries for a deep, blood-red hue. Nonya Oeij Soen King understood that in an age when printed fabrics were flooding the market, a good piece of batik had to be everything a printed fabric was not.

Nonya Oeij Soen King often used mengkudu root to achieve the deep red hue visible in works such as this cotton kain panjang.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

“Batik-making was also very competitive in the late 1800s and early 1900s,” Mr Lee notes.

“The best way to ensure that your design could not be copied was to make it almost impossible to do so. This is bespoke at the highest level. Her works were hand-drawn batik tulis by skilled artisans to avoid any mechanical repetition in terms of motif, order and size.”

While many of Nonya Oeij Soen King’s designs reference classic Javanese patterns, she disrupts these with idiosyncratic touches, such as birds and flowers that each have unique isen (Bahasa Indonesia for “filler patterns”), or a whimsical winged garuda (“eagle”) with a flowering plant replacing the mythological creature’s usual fantail.

This cotton kain panjang by Nonya Oeij Soen King features a garuda motif with a flowering plant for a tail.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

“When you read each textile, the rhythmic visual counterpoints she creates are astonishingly masterful and modern, much like jazz. She is constantly breaking regularity, and yet there is still a structure, creating a dynamic play between precision and ambiguity,” says Mr Lee.

Breaking the mould with ink-stamped works

Her daughter-in-law Nonya Oeij Kok Sing (1895 to 1966) understood this benchmark for creating one-off batiks.

Fortunately, both women had clients who appreciated fine tulis sarongs and kebayas, and who could afford this level of artistry.

Nonya Oeij Kok Sing, though, expressed this differently. She had likely apprenticed under her mother-in-law and struck out with her husband, Mr Oeij Kok Sing, in the mid-1920s.

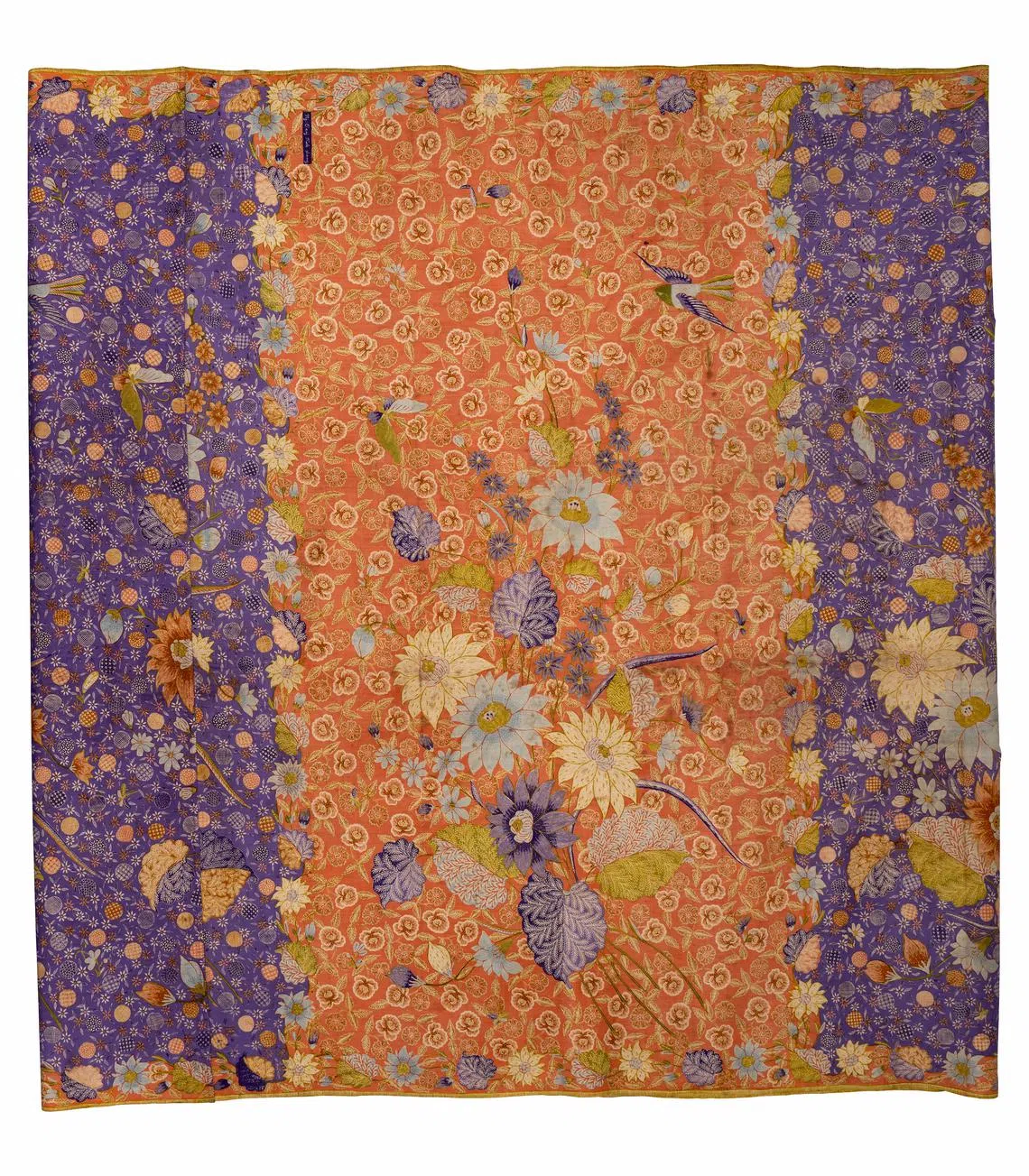

The vibrant colours in this 1939 cotton sarong by Nonya Oeij Kok Sing reflect the wider variety of dyes available at the time.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

One distinctive aspect of her craft is the dated ink stamp she applied on many of her works. Mr Lee says this makes her unique in the history of batik. Because of this, historians are able to trace her artistic evolution from 1929 to 1941.

Nonya Oeij Kok Sing initially produced well-crafted, conventional batik sarongs, representing what was generally being created in high-end commercial ateliers in Pekalongan at that time.

“By the early 1930s, something inspired her to charge up her designs,” Mr Lee says.

“The high-octane intensity of her colours, the exuberant ambiguity of her idiosyncratic motifs – something she picked up from her mother-in-law – characterise her style.”

The family still has many of the templates she pencilled on grease-proof paper, showing the confident lines of her drawing, revealing how hands-on she was artistically.

A close-up of a cotton batik sarong by Nonya Oeij Kok Sing. It was likely made between 1939 and 1941.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Around this time, European synthetic dyes flooded the batik market and makers suddenly had at their disposal an astonishing range of colour tones to experiment with, says Mr Lee.

Dye companies and entrepreneurs published dye recipe books. Some makers kept the formulas for special colours a secret.

Nonya Oeij Kok Sing developed a palette that combined electric blues and pinks with pale pastels such as lavender and sky blue, and earthy tones such as mustard green.

“Like her mother-in-law, she believed the only way to prevent copies of one’s work was to never repeat any design,” Mr Lee says.

Batik couture for a modern world

On the other hand, Jane Hendromartono (1924 to 1988, also called Oeij Djien Nio) was active at a time of great political and economic upheaval.

The period was marked by the end of Dutch colonialism, the Japanese Occupation, the birth of the new Indonesian republic, changing tastes in fashion – which included the decline of the sarong kebaya among Peranakans – and the rise of modern national styles.

But Hendromartono made a name for herself as an artist and designer through her ability to respond to these changes.

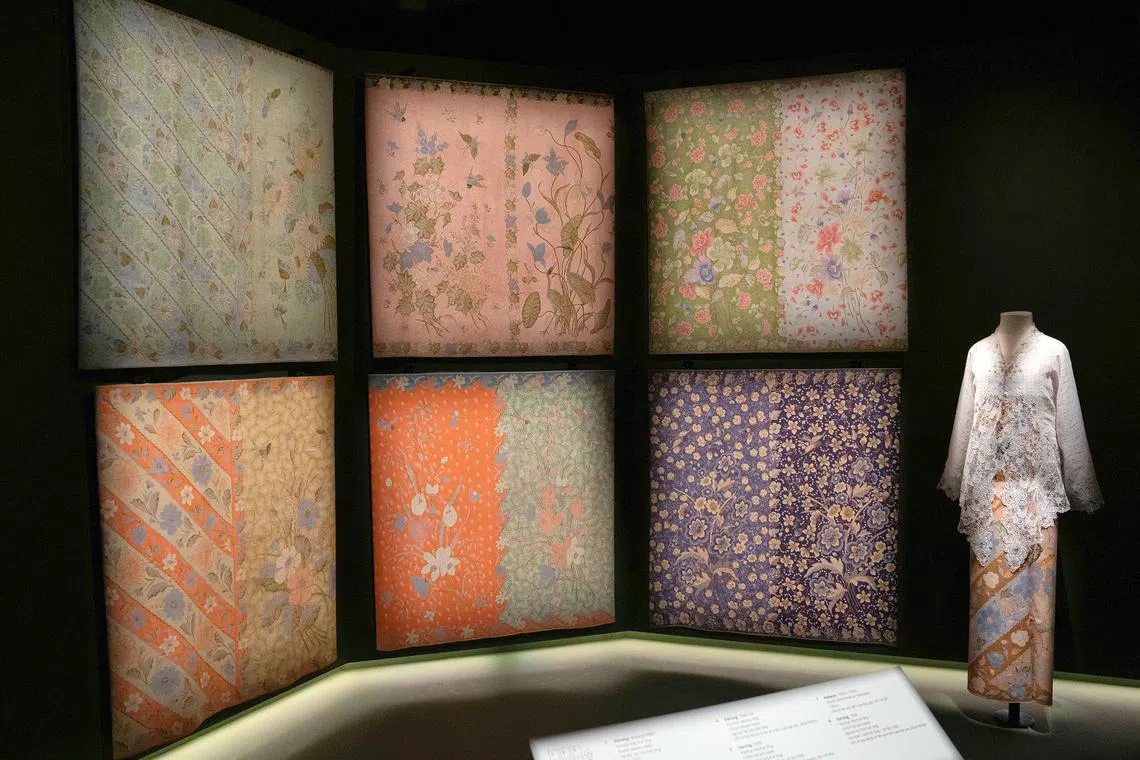

Her earliest designs from the late 1940s catered to the tail-end of the Peranakan demand for luxury batik tulis. These were termed “Kudus style”, named after the town in Java that originated this pointillist batik style. They had the highest dots per inch (DPI) among all batiks made at the time.

A close-up of a cotton batik kain panjang made by Jane Hendromartono, likely around the late 1940s to early 1950s, in the pointillist Kudus style.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Hendromartono imbued her take on this style with elements she invented, often drawn from Chinese culture.

But with the rise of a nationalistic style of batik promoted by President Sukarno in the 1950s and later President Suharto in the 1980s, Hendromartono changed her production to cater to this very different style.

With new legislation affecting Chinese Indonesians, she and her husband adopted the Indonesian name Hendromartono.

They also relinquished the three-generation atelier in their house in Pekalongan, embarking on fruitful collaborations with several local Javanese producers.

Motifs drawn from courtly batiks and new national symbols were set against the bright hues of Pekalongan, a style favoured by modern Indonesian women wearing kebaya kutubaru (blouses with a decolletage flap) and batik kain panjang (“long cloth” in Bahasa Indonesia). It is a long skirt cloth wrapped around the body, rather than sewn as a tube for a sarong.

Giant flying phoenixes with swirling tails, and small repeated motifs of Balinese temples, were some of her design contributions to this new aesthetic.

A cotton batik kain panjang made by Jane Hendromartono around the late 1960s to early 1970s. Some of her contributions to the aesthetic of the time include phoenix and temple motifs.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Some of her designs were also made as yardage for the burgeoning world of Indonesian couturiers.

Hendromartono developed designs based on her mother’s and grandmother’s work, found new foreign clients – some of whom had arrived in Indonesia as travellers – and established batik businesses in Europe and America.

“Jane remained active up to her passing in 1988. In her later years, she also pivoted towards mass production of block-printed batik (batik cap) material for home furnishings and table linens for the export market,” says Mr Lee.

“The patterns could be derived from typical Pekalongan-style floral batiks to those that conveyed modern pop cultural sensibilities, such as a repeat design of watermelons.”

‘Unique and eclectic styles’

Professor Barbara Watson Andaya, a lecturer of Asian studies at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa in Honolulu, Hawaii, was one of the first to view the exhibition during a visit to Singapore in September 2024, a few weeks before the official launch on Oct 11 that year.

She would like more Singaporeans and residents to carve out time from their busy schedules to catch the exhibition before it ends in three months.

“You could spend the entire day at the museum, yet there is so much to absorb that it is worth a second visit so you can return to the batiks that you liked the best, and appreciate the extraordinary talent and effort that was involved in producing such beautiful pieces,” Prof Andaya tells The Straits Times.

“I think, sometimes, the citizens of a modern city such as Singapore forget that they are heirs to an amazing artistic legacy that can be seen not only in architectural designs and contemporary art, but also hidden away in people’s homes – in old furniture, carvings, embroidery and, of course, batik in its many forms.”

Prof Andaya, whose career includes teaching and researching in Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, the Netherlands and Hawaii, adds: “After going through the exhibits prior to the opening, I believe most visitors have little idea of the teamwork involved, and the care and thought about matters like placement and lighting that we take for granted.”

She says people also tend to forget the women and girls behind textile production, and for that reason, the photos in the exhibition have a lot to tell.

“My takeaway was the extraordinary variety of the designs, and the way in which each of the three Nonyas had crafted a range of unique and eclectic styles in both motifs and colours. In many ways, I felt these artists were also responding to real or imagined clients.”

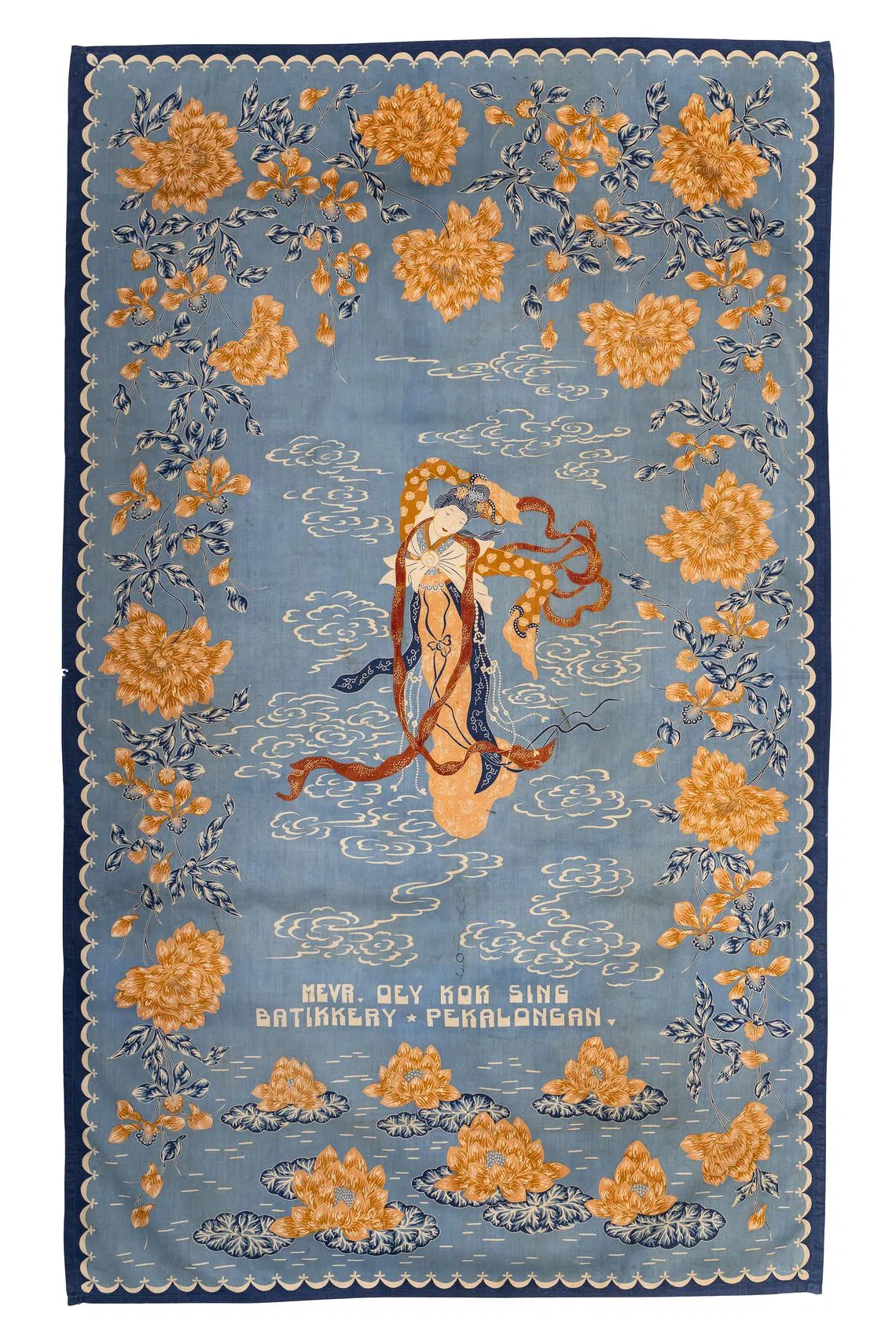

This 1941 hanging cotton piece by Nonya Oeij Kok Sing may have been inspired by Peking opera performers.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Prof Andaya maintains an active teaching and research interest across South-east Asia, but her specific area of expertise is the western Malay-Indonesia archipelago.

She highlights one exhibit by Nonya Oeij Kok Sing, created in 1941 on the eve of the Japanese invasion. This, Prof Andaya says, stood out to her because of its border of chrysanthemums surrounding a figure, perhaps inspired by a Peking opera icon such as Mei Lanfang.

“I wonder if something like this might have found its way back to a home in Beijing?” she asks.

“I could pick out other designs, as well as examples of artistic dexterity, like the batik trousers by Mrs Oeij Soen King, the mother-in-law of Mrs Oeij Kok Sing, where diagonal stripes of flowers and butterflies are interspersed with depictions of fantastical birds and animals.

A 1971 cotton kain panjang by Jane Hendromartono, featuring a print of elephants and palm trees.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

“And because I used to collect elephant prints, I was thrilled to see Jane Hendromartono’s batik of elephants and palm trees for Prince Bernhard.”

The late Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld, husband of the former Queen Juliana, was Prince of the Netherlands from 1948 to 1980. He was also the first president of the World Wildlife Fund from 1961 to 1976.

Thriving in a diversity of identities

Mr Alan Chong, former director of ACM and the Peranakan Museum, says Peranakan culture is often thought of as the Chinese-Malay hybrid communities based in Penang, Melaka and Singapore.

But it is in fact much larger, with a reach throughout Java and Sumatra, as well as Thailand and the Philippines.

Peranakan culture, he says, offers insights into how mixed communities develop and thrive.

“Hybridity in dress, food, business and faith have been part of South-east Asia for centuries,” says Mr Chong, who holds a bachelor’s degree in art history from Yale University and a PhD in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, specialising in 17th-century Dutch art, Renaissance patronage and the global movement of art objects.

“The Oeij family realised they were producing works of art as well as commercial products. Even a century ago, they carefully kept the best batiks to preserve their work and trace their stylistic development.”

The Batik Nyonyas exhibition celebrates the works of the Oeij family.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Art enthusiast Sarah Tong, who saw the exhibition in November 2024, says it was an eye-opener not only in the breadth of batik art and design it presented, but also in how thoughtfully it was curated.

“What struck me most was how the works were presented in a narrative arc that followed the lives of three generations of batik-makers, illustrating both their life and artistic developments,” she says.

“I appreciated that it contextualised the evolution of batik alongside the broader socio-political shifts in Pekalongan and Indonesia – from a multicultural port city, through the periods of colonial trade and persecution, and globalisation,” she adds.

“This dynamic lens through time challenged the notion of batik as purely ‘traditional’. Instead, it portrayed batik as a living, evolving art form driven by cultural expression and entrepreneurship.”

Storytelling in the galleries by "The Storytelling Fairy" Nadya Hashim during the Batik Nyonyas Weekend Festival in April.

PHOTO: THE PERANAKAN MUSEUM

Mr Lee says batik, as a technique, is taught in schools across the world and that anyone can make a textile by wax-resist dyeing and try to express his or her personal artistry or national culture through this method.

“However, Javanese batik has a unique place in this history, and it is important to understand that many patterns and motifs in batik around the world originally emerged in production centres such as Surakarta, Yogyakarta, Cirebon and Pekalongan.

“It is vital to recognise Indonesia’s important contribution to this time-honoured art and design form.”

Batik’s design evolution

Batik’s origins in Indonesia date back at least five centuries, from its roots in the Javanese royal courts to its role as a dynamic, living art form shaped by cross-cultural exchange.

In 2009, Indonesian batik was inscribed in Unesco’s Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, recognising it as a treasure of Indonesian culture and artisanal heritage.

India was the commercial source of batik and other cloths in the archipelago from at least the 14th century. Block-printed and resist-dyed textiles known in India as kalamkari, were made specifically for South-east Asia in Gujarat, the Deccan and Bengal, and exported in massive quantities.

The fact that the terms for the textiles were Indian or Malay, and sometimes a combination of both, suggest a dynamic two-way economic and cultural relationship in this trade.

The inland Javanese courts started producing their own batiks from the 16th century. As trade expanded along Java’s northern coast, batik absorbed influences from Chinese, Arab and later European cultures.

This gave rise to vibrant coastal Javanese (pesisir) batik, known for its bright colours, floral and pictorial motifs, and fusion of local and foreign aesthetics.

Batik also spread to other regions and ethnic groups, inspiring stylistic variations in Sumatra, Kalimantan and beyond.

Royal patterns of Batik Keraton

By the 16th century, batik had become a refined courtly art in Central Java, especially within the royal palaces, also called “keraton”, in the Mataram Sultanate, and later in the states of Yogyakarta and Surakarta.

The Mataram Sultanate was a Javanese kingdom that existed in South Central Java between the 16th century and 1755, when it was formally divided. It is known for its Islamic influence and prominent role in shaping Javanese culture and history.

It is also called “pedalaman” or inland batik. While the coastal cities exhibited a range of design influences, people from the heartland usually preferred less experimental and more classic batik designs.

Skilled artisans here developed intricate motifs using natural dyes and wax-resist methods, with specific patterns reserved for royalty and religious ceremonies.

The motifs featured symbolic meanings tied to power, spirituality and Javanese cosmology. The designs are in earthy tones such as brown and indigo derived from natural dyes, as well as white, the colour of the base cloth.

Coastal designs of Batik Pesisir

The northern Javanese coastal cities of Pekalongan, Cirebon, Lasem and Madura developed a range of bold and experimental styles through trade with China, India, Arabia and Europe.

The designs reflected a cultural melting pot of styles influenced by the Javanese, Peranakan Chinese, Arab, Dutch and Eurasian entrepreneurs involved in the batik business.

Naturalistic designs featuring florals, birds and phoenixes started appearing in the 1890s in small ateliers that sprung up around Java’s northern port cities, together with European lace patterns. These were often combined with the wide and complex repertoire of patterns derived from those of the Javanese royal courts.

There were also Chinese-influenced works, such as the “megamendung” or cloud motifs of Cirebon, and Pekalongan “buketan” (bouquet) designs initiated by Dutch and Eurasian batik-makers.

Batik from indigenous communities

Indigenous communities in several parts of the Indonesian archipelago have created their own designs over the centuries.

Unlike the royal batik of Java or the coastal batik pesisir, the batik of the island communities reflects their animist and ancestral beliefs, including Dayak Batik from Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), Batik Tabir from the Riau islands and Batik Tanah Liek from West Sumatra.

Batik Tanah Liek, or “clay batik”, is a unique form of Indonesian batik from the Minangkabau region of West Sumatra.

Minangkabau batik stands out due to its distinctive production process, which uses clay as a colouring agent.

Malaysian batik

Malaysian batik is a distinct art form shaped by trade, cultural exchange and local innovation.

Batik-like textiles called “kain pukul” were produced in the Malay peninsula using wooden block stamps before the 20th century.

Trade with Javanese coastal cities such as Cirebon and Lasem introduced Javanese batik motifs and techniques, particularly influencing regions such as Jambi in Sumatra and Kelantan in the Malay Peninsula.

A strong Islamic influence is reflected in the motifs, designs and even the use of batik for religious purposes.

Islamic beliefs and practices, such as prohibitions on realistic depictions of animals and humans, led to the development of more abstract and geometric designs and the inclusion of Quranic inscriptions known as batik besurek.

How batik is made

Batik was first made by hand using the wax-resist method with a stylus or a block made of wood or copper. Over the years, new interpretations in the craft have changed its look and feel.

In the modern era, batik continues to evolve, with new techniques, contemporary designs and sustainable practices, while remaining a vital expression of Indonesian heritage.

Batik tulis: This refers to the earliest beginnings of wax-resist dyeing, when batik designs were drawn by hand (“tulis” in Bahasa Indonesia). A stylus with a well for the wax, called canting, is filled with melted wax and used to draw a design on the cloth to prevent dye from penetrating certain areas.

The fabric is then immersed in a dye bath. The wax acts as a barrier, preventing the dye from penetrating the areas covered in wax. After dyeing, the wax is removed by boiling the fabric, which reveals the batik pattern. The process is repeated multiple times, with different wax applications and coloured dye baths, to create complex, colourful designs.

Batik cap: The invention of copper stamps in batik cap in the mid-19th century, and the introduction of synthetic dyes in the late 19th century, made batik production faster and more affordable, opening up a wider market for the textiles. Copper caps reduced production times from about four months to just a few days.

Mass production: With machine printing in the 20th century, textiles with batik patterns became more affordable for everyday wear, not only for Javanese communities but also for customers across the region.

Experimental designs: A fusion with digital art and abstract, contemporary themes has resulted in “batik-inspired designs” in the last few decades in South-east Asia. These pay homage to the ancient art form using new palettes, but have limited appeal to batik purists.

Designer and lifestyle journalist Chantal Sajan writes on design and architecture.

Book It / Batik Nyonyas: Three Generations Of Art And Entrepreneurship

Where: The Peranakan Museum, 39 Armenian Street str.sg/8763

MRT: City Hall/Dhoby Ghaut

When: Till Aug 31, 10am to 7pm daily, and till 9pm on Fridays

Admission: Singapore residents get free entry to permanent galleries and pay $6 for special exhibitions; tourists pay $18 for access to both

Info: