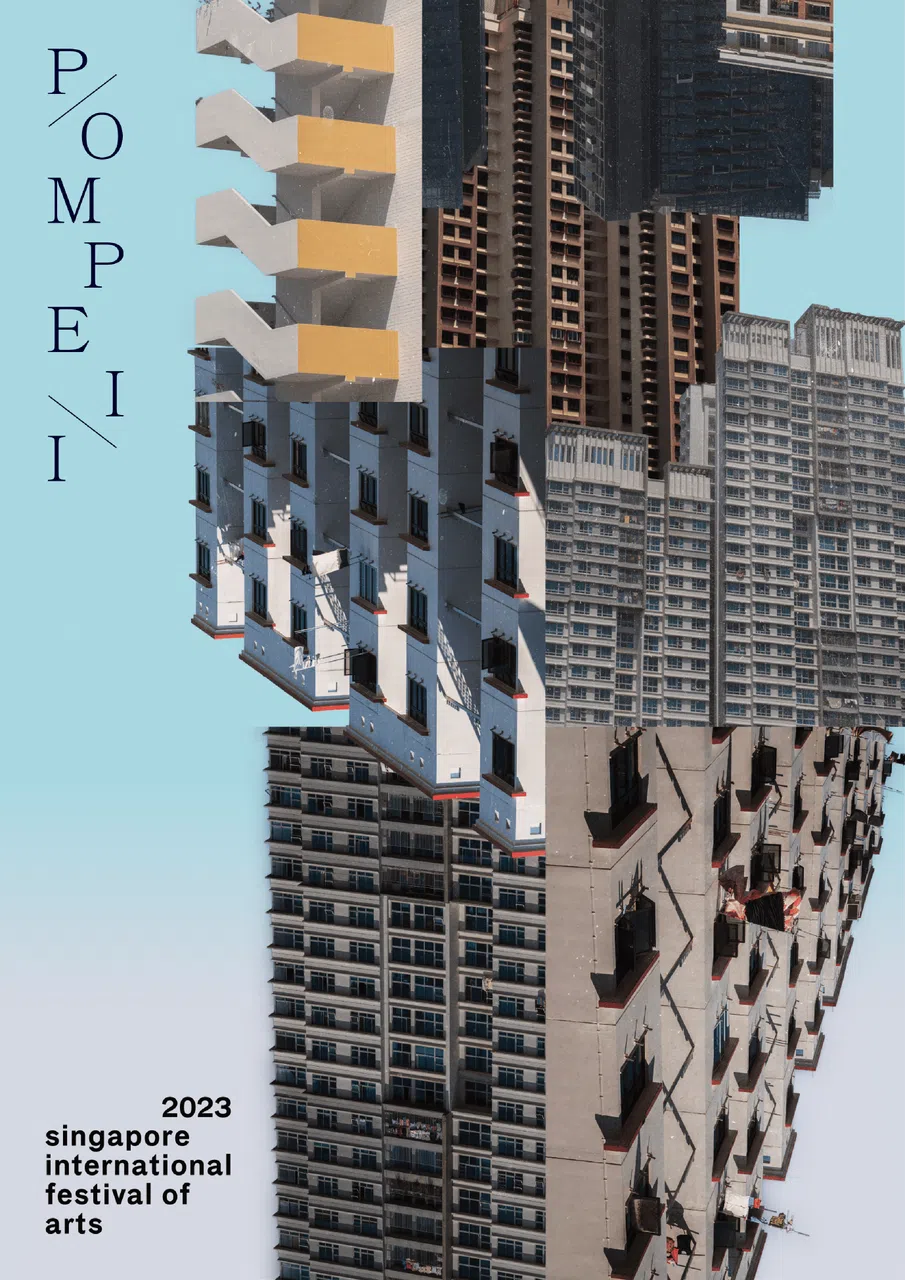

Theatre review: Pompeii a cerebral essay on death and the things people leave behind

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Follow topic:

Singapore International Festival of Arts

Pompeii

Edith Podesta and K. Rajagopal

Drama Centre Theatre

Last Friday, 8pm

There is some self-indulgence in this twilight meditation on death devised by theatre veteran Edith Podesta and film-maker K. Rajagopal, which combines theatre and cinema in a “split horizon” approach to give quiet send-offs to seven characters living in a Singapore condominium called Pompeii.

The actors’ movements are shot close-up, through mirrors and the occasional Dutch angle, and displayed in real time on a large screen hanging above the stage.

A languid voiceover by Remesh Panicker gives it the feel of an elegiac documentary and it is through his archly philosophising narrative that the audience gains access to the characters – just as well, for there is little heard dialogue between them, the artifice of artmaking blatant with camera crew hauling equipment across the stage.

The effect is a sort of essay-performance on how people’s things create spaces and houses that are bound to outlive them and say more about their lives that they could ever hope to conceal.

It is a cerebral engagement that does not shy away from using its actors as props to make its point, though Panicker’s narrator might use words like “cerebellum” or “hypothalamus” to amp up his thesis.

Pompeii opens seven hours before an unnamed catastrophic event is to befall the inhabitants of the condominium, named after the Italian town buried under pyroclasm in AD79.

There is an old man, the expat, played tremulously and with the most subtlety by Helmut Bakaitis; Sharon Au’s Japanese-speaking architect, pined after by a reticent composer (Futoshi Moriyama); an estranged couple (Pavan J. Singh and Koh Wan Ching) afflicted with empty nest syndrome and other sadness, some perhaps introduced too abruptly; and a too-nosy cleaner (Cindy Yeong) and her daughter (Lauren Teh), on the cusp of womanhood as she experiences her first menstrual cycle and learns grief in the form of her dead dog.

Each is to have his or her story told by Panicker, who freewheels from Plato to Oscar Wilde in an omniscient survey. This intercession, flushed with a pointed literary quality, sacrifices audiences’ emotional connection with the characters for a grander existentialism.

It is to unsure effect. For every well-crafted line – “A cracked lip (of a mug) still forms vowels and speak” – there is a Tumblr-viral “to be alone in a room is not the same as feeling alone in a room”.

His resonant half-rhymes (“shrapnel in his thigh/as men around him die”) must be balanced against the by-now trite ideas of the light of stars taking days or months to reach the earth, and what this means for people’s capacity to reach forward through time to affect posterity.

But hit-and-miss as it is, this Archimedean script is beautifully read and, when properly integrated with other elements, some of the juxtapositions are powerful.

In the opening sequence, the sports commentary for Liverpool’s destructive 7-0 number over Manchester United is rousingly overlaid by Panicker’s description of an ancient Roman victory procession.

Shot in close-up, Singh’s Liverpool supporter’s eyes are opaque behind spectacles as he watches this thrashing on his phone screen. Panicker begins talking about a slave designated to trail the Roman general in his triumph, whispering memento mori into his ear to remind him of the essential meaninglessness of his victory.

Later, the full tragedy of this is revealed, as audiences learn that Singh is watching this in the aftermath of the death of his friend, a Manchester United fan. This friend had given him a Liverpool mug that is now chipped and which he refuses to throw out.

Rajagopal’s camerawork is essential here, weaving in and out of the condo units on stage determinedly not built for full visibility.

Though mostly unintrusive, there are tinges of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa in the way it boldly switches angles mid-action in the black-and-white footage.

A well-timed cut seamlessly links a door shutting with another opening, though it is also unafraid to rest, lingering on the composer as he performs a funerary ritual for a sewing needle – a rite not really integrated into the rest of the play but which captures the call to be more aware of the “consciousness” of things.

Pompeii opens seven hours before an unnamed catastrophic event is to befall the inhabitants of the condominium, named after the Italian town buried under pyroclasm in AD79.

PHOTO: SIFA

The finale is an apocalyptic rendition of W.H. Auden’s As I Walked Out One Evening that is genuinely affecting, the Liverpool mug once more playing a trenchant role in the line: “And the crack in the tea-cup opens/A lane to the land of the dead.”

It is not exactly moving fare, but a worthwhile time capsule of Covid-19’s reminder of human mortality, told in a way full of art.