Shuntaro Tanikawa, poet and translator of Peanuts, dies at 92

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

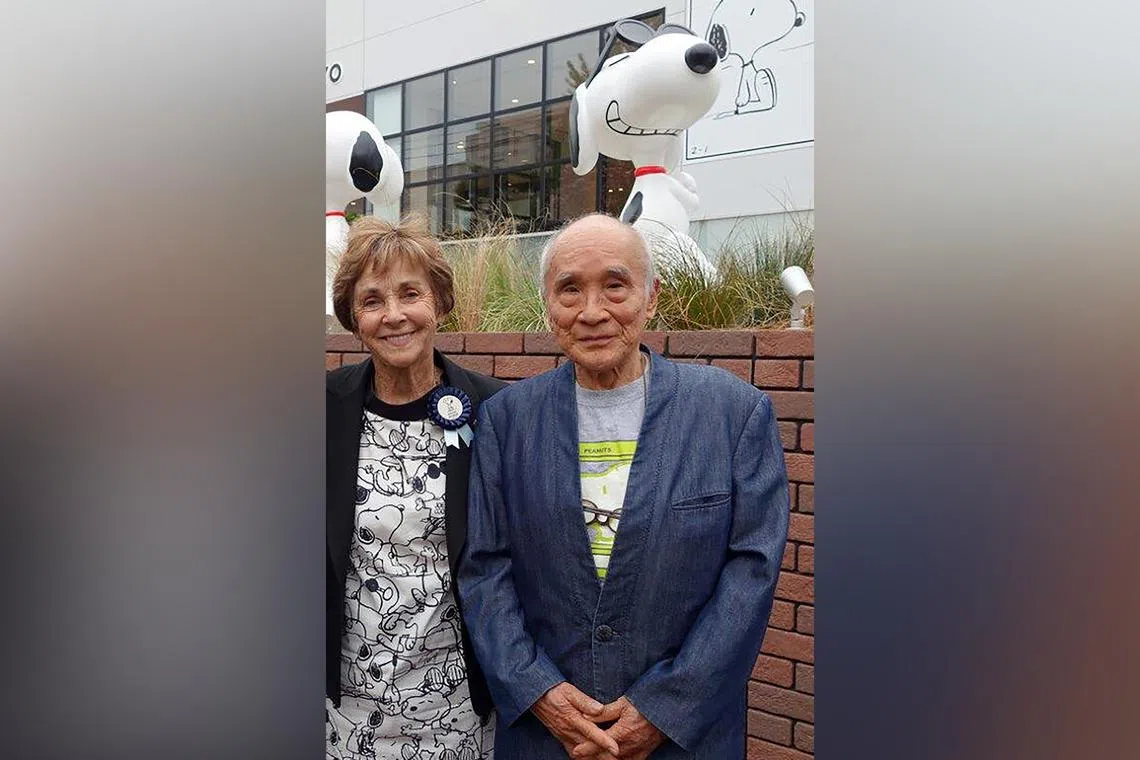

Shuntaro Tanikawa, Japan’s most popular poet for more than half a century, died on Nov 13 in Tokyo, at age 92.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

TOKYO – Shuntaro Tanikawa, Japan’s most popular poet for more than half a century, died in Tokyo on Nov 13, at age 92. His stark and whimsical poems, blending humour with melancholy, made him a kind of everyman philosopher ideally suited to translating the Peanuts comic strip and Mother Goose rhymes into Japanese.

The death at a hospital was confirmed by his daughter, Ms Shino Tanikawa, who did not specify a cause.

A perennial front runner for the Nobel Prize in literature, Tanikawa was a revered figure in Japan, not just in literary circles, but also among casual readers. It was common to see commuters reading his books on the subway.

He published more than 60 collections of poetry, beginning in 1952, when he was 21, with Alone in Two Billion Light Years – a book that heralded a bold new voice who shunned haiku and other traditional Japanese forms of verse.

In the title poem from that collection (translated by Mr Takako Lento), he wrote:

On this small sphere

humans sleep, wake, work

from time to time want friends on Mars

I don’t know what Martians do

on their small sphere

(maybe they sleep’eep, wake’ake, work’ork)

but from time to time they want friends on Earth

that’s absolutely for sure

Universal gravitation is

the force of being alone, attracting each other

The universe is warped

that is why all of us seek each other

The universe is growing fast

that is why all of us are uneasy

Standing alone in two billion light years

I sneezed, in spite of myself

Being alone and sneezing at the universe’s bewitching tendencies were sentiments that echoed throughout Tanikawa’s writing. In poems like Before We Were Born, At Midnight In The Kitchen I Wanted To Talk To You and A Morning Takes Shape, he sketched the quotidian, beguiling and lonesome moments of daily life.

In Can You Hear, he wrote:

Can you hear the quiet

that lurks between lovers at dusk?

Can you hear that quiet

in the gentle eyes of a deer looking at you

can you hear the quiet

the sky is always secretly hiding?

“My poetry is the expression of a moment rather than of history,” he said in a 1998 interview with the Australian literary journal Southerly. “I often say this: The novel captures events within a certain time frame. But poetry, I believe, cuts through life to reveal a cross-section of experience.”

That point of view made him a vital voice in Japanese letters after World War II, when hundreds of literary journals emerged amid the nation’s economic and cultural recovery.

Many writers, especially poets, continued to work in traditional Japanese forms, but not Tanikawa.

“I think that is the core of his popularity,” Mr Lento, who translated Tanikawa’s The Art Of Being Alone: Poems 1952-2009 and who died recently, said in an interview. “Anyone from a young child who has no life experience to a senior literary critic can see something substantial in his work.”

In the late 1960s, as Western pop culture took hold in Japan, a local publisher hired Tanikawa to translate Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts into Japanese.

Peanuts collections were bestsellers in Japan, and eventually Snoopy-branded stores, hotels and cafes popped up throughout the country. In 2016, the Charles M. Schulz Museum opened a satellite outpost in Japan called Snoopy Museum Tokyo.

Cultural critics, podcasters and even academic publications like the Journal of General Management have, over the years, sought to unravel the popularity of Peanuts in the country.

One reason they point to: Schulz’s simple drawing style, which mirrors the sleek, stark aesthetic of Japanese design and pop culture.

Another reason: Tanikawa’s extraordinary ability to mimic the voices of Peanuts characters, whose philosophical sensibilities – encapsulated in Snoopy’s line, “You play with the cards you’re dealt… whatever that means” – resonated with Japanese society.

Tanikawa and Schulz’s widow, Ms Jean Schulz, discussed the poet-cartoonist mind meld during a 2016 conversation published in one of the Schulz Museum’s exhibition catalogues.

“I had the impression that he was like a philosopher,” Tanikawa said, according to a translation of the conversation provided by the museum. He added: “I think Snoopy is a dog sometimes becoming really close to how humans feel.”

Tanikawa was born on Dec 15, 1931, in Tokyo to Tetsuzo and Takiko (Osada) Tanikawa. His father was a philosopher and a university professor.

Shuntaro Tanikawa did not excel in high school, which he hated. He did not attend college and did not dream of becoming a poet.

“I didn’t start writing poetry because I liked it or read a great deal of it, or because I wanted to become a poet,” he told Southerly. “My relationship with poetry is best described as more of an arranged marriage than a love match. Without knowing exactly what poetry was, I simply wrote about how I felt in the same way as young people write in a diary.”

One day, he recalled, his father asked him: “If you’re not going to university, what are you going to do?”

He showed his father some poems.

Mr Tetsuzo Tanikawa liked them and, using his university connections, sent them to Japanese poet Tatsuji Miyoshi, who thought the writing showed promise. Miyoshi helped him get several poems published in a literary magazine.

Shuntaro Tanikawa’s poetry has been translated into more than 20 languages, including several collections in English. In addition to translating Peanuts and the Mother Goose rhymes, he wrote the lyrics for the theme song to the popular TV cartoon series Astro Boy.

His marriages to Ms Eriko Kishida, Ms Tomoko Okubo and Ms Yoko Sano ended in divorce. In addition to his daughter, he is survived by his son, composer Kensaku Tanikawa; a stepson, Mr Gen Hirose; four grandchildren; and a great-grandson.

Tanikawa was frequently asked by younger poets how they should go about writing poetry. His advice was typically pithy.

“I tell them to find a poem they like,” he said. “I’ve got to the stage where I can get away with this sort of thing, but in the final analysis, it ends up with me saying that people who write poetry were born to write poetry.” NYTIMES