Shawn Hoo’s top reads of 2025: Arundhati Roy, Ng Yi-Sheng and Wahidah Tambee

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

(From left) Poet Wahidah Tambee’s Eke, Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes To Me, and Ng Yi-Sheng's Utama.

PHOTOS: GAUDY BOY, HAMISH HAMILTON, EPIGRAM BOOKS

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE –In 2019, when Singapore was commemorating the bicentennial of Sir Stamford Raffles’ arrival in 1819, four new statues rose up along the Singapore River next to Raffles’ – one of which was of Sang Nila Utama, the 13th-century Palembang prince who founded Singapura.

Statues simplify history – and every man placed on a literal pedestal is open to have his legacy interrogated and complicated. Writers have rightly done so with the British colonial officer and, in 2025, Sang Nila Utama is being cast in a brilliant and complicated light by Singaporean writer Ng Yi-Sheng.

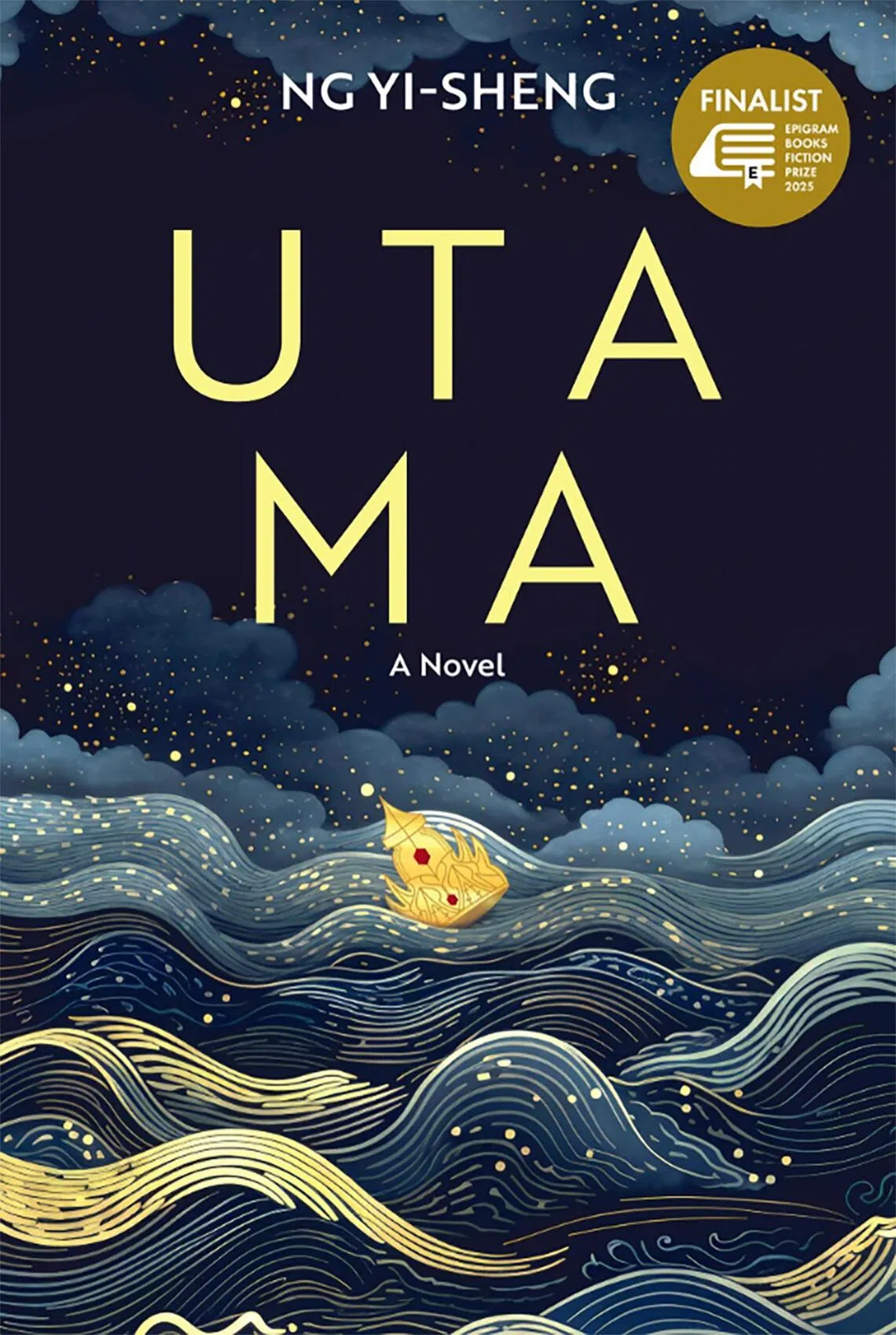

The two-time Singapore Literature Prize-winner’s Utama

Home-grown writer Ng Yi-Sheng's Utama tells the story of Singapura founder Sang Nila Utama through the dispossessed.

PHOTO: EPIGRAM BOOKS

A beautifully written scene in the middle section of the book has stayed with me. The women of Palembang, disposed of by their lusty prince who has taken 39 wives, take shelter in a Mahadewi shrine and start a new life in a women-centred community. In spell-binding prose that blends fantasy and history, Ng’s Utama should be compulsory reading as Singapore continues to reckon with its past.

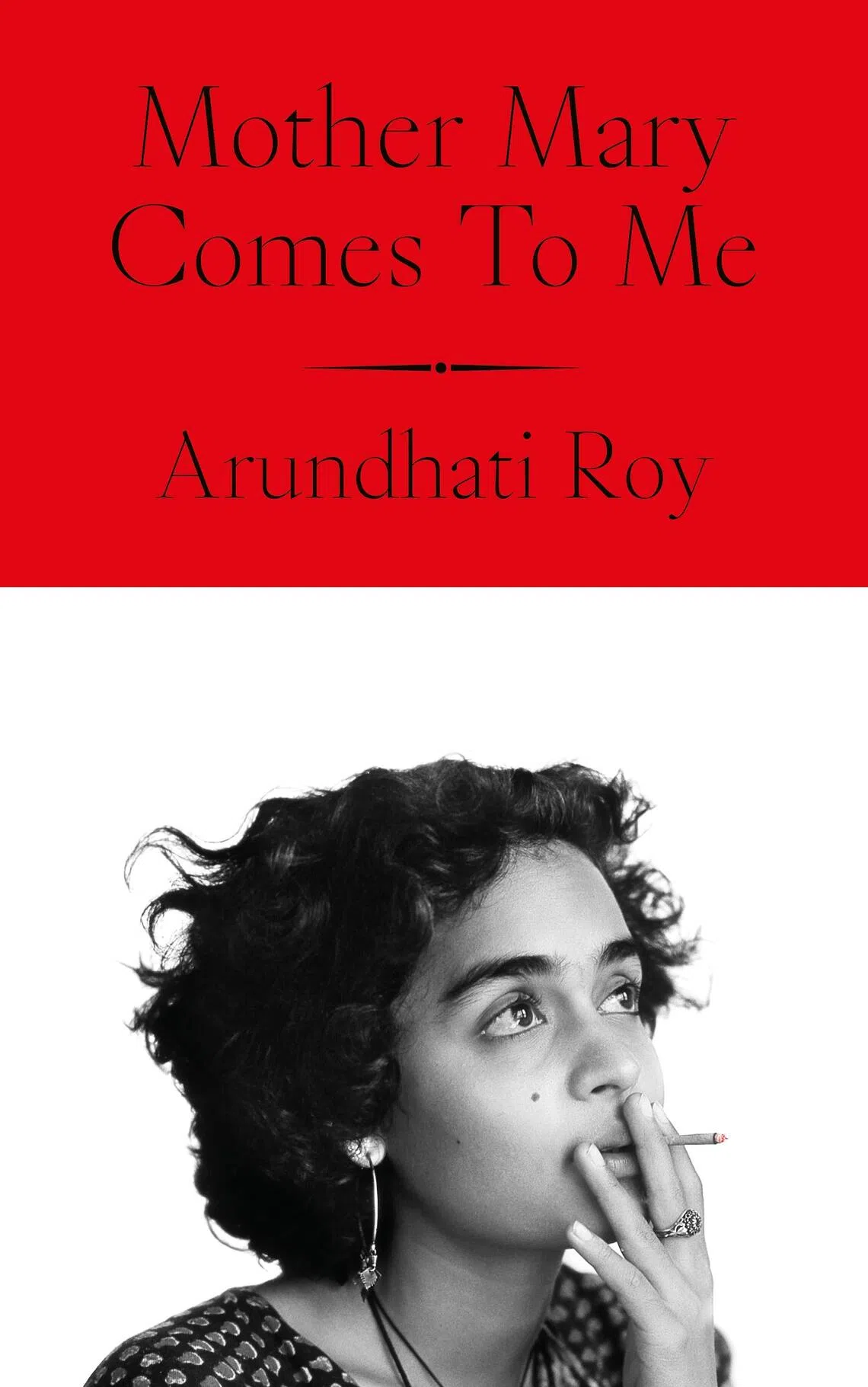

Within the family home, too, there are complicated legacies. Booker Prize-winning author Arundhati Roy’s first memoir Mother Mary Comes To Me

Indian writer Arundhati Roy's first memoir Mother Mary Comes To Me (2025) recalls her mother, who was at once hailed as a feminist trailblazer and was mercurial and cruel at home.

PHOTO: HAMISH HAMILTON

The work is a rare look at the childhood of Roy, who has more consistently written explicitly political books on topics such as Naxalite communist guerillas, destructive dam projects, Hindu nationalism and global capitalism. Her earlier books are banned in Indian-administered Kashmir, but Roy remains a resolute writer of conscience.

But this is not a book devoid of politics. It, in fact, can be read as an origin story of Roy’s political beliefs. She writes of her mercurial mother’s influence: “The way she was with him (Roy’s brother) has queered and complicated my view of feminism forever, filled it with caveats.”

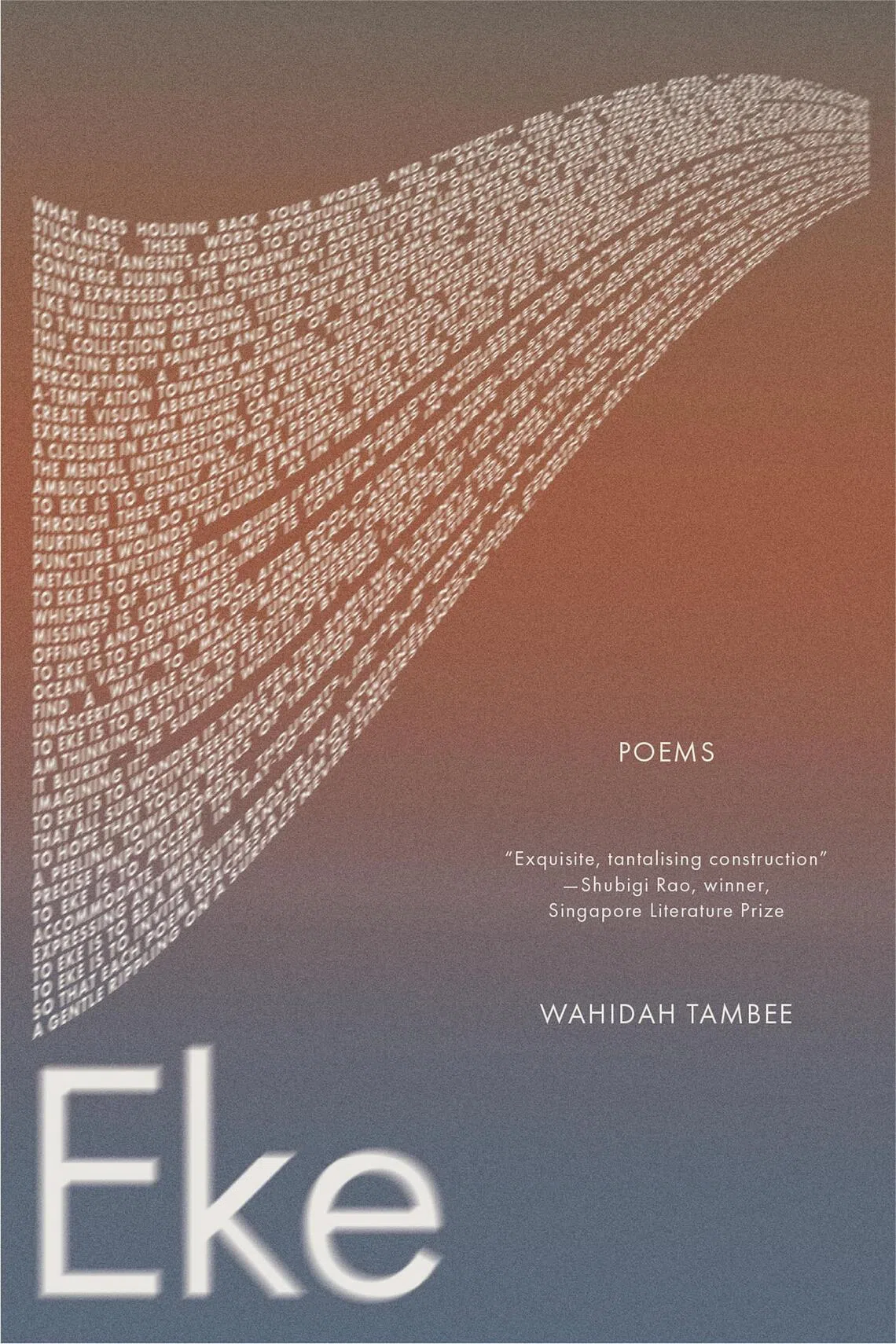

My Singapore poetry book of the year is poet Wahidah Tambee’s Eke

Eke is Singaporean poet Wahidah Tambee's first poetry collection.

PHOTO: GAUDY BOY

The collection’s palindromic title consisting of merely two different letters is perhaps emblematic of the book’s economy and ethos of whittling words down to their bare essentials – a rare adventure in concrete poetry in Singapore. Its title, too, suggests the difficulty of producing meaningful language, which is apt for a year that has been flooded with texts by large-language models.

This mesmerising debut collection plays with typography to bring out the stutters in seemingly innocent everyday words. The poems – which resemble little islets of words – have an affinity with text-based art and selected poems have recently been brought out in limited broadside editions.

Poetry might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but try to see how you read these poems aloud and ponder a few of them a day. You might just find your view of ordinary words upended and refreshed.