Old Singapore’s fire, girls and gang gods in When They Burned The Butterfly

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Wen-yi Lee, author of When They Burned the Butterfly, a 2025 historical fantasy novel set in 1970s Singapore.

ST PHOTO: JASON QUAH

Follow topic:

When They Burned The Butterfly

By Wen-yi Lee Fiction/Tor/Paperback/464 pages/$34.95

There is a tendency for younger, earnest writers finding a shortcut to febrile emotion or untenable stakes to reach too easily for God.

So, there was concern when this highly anticipated first book of Wen-yi Lee’s duology invoked capital G “God” from the get-go. Its first sentence reads: “Adeline stared at the back of Elaine Chew’s head and thought about setting God on fire.”

One need not have worried. Lee easily bats away the scepticism, serving up one of the archest starting chapters by a Singaporean author in recent memory, everything delivered with a wink.

God and fire are her subjects, as she torches a devastating, cathartic path through the dark underbelly of Singapore – the secret societies, prostitutes, tattooists, undertakers and quack doctors revelling in their own ambition and vengeance, as the rest of Singapore moves rapidly on in the 1970s.

In Lee’s imagining, this was a time of traditional magic under assault, the police rounding up too-fervent displays of power, pressure leading to gangs betraying one another and adopting radical new science to survive. Even deity statues are being stolen from temples.

Meanwhile, the new temples – shopping centres – are being erected, only glancingly referred to to keep the noirish pressure. There is a nice historical detail of People’s Park Complex’s atrium filled with weighing scales as part of a public campaign to familiarise people with the new metric system.

But everything is subservient to Adeline’s fire.

Readers first meet the secondary school girl nursing a flame on her fingers in the school toilet as she skips out on a mandatory sermon. It appears to be a unique skill passed down from mother to daughter. With Adeline taught to keep it small and hidden, the first few chapters have an almost realist feel about them, the flame legible as teenage girl rage that will be tamped down over time into bourgeois normality.

Until the first of Lee’s cinematic set pieces thrusts Adeline into the milieu of other fire-conjuring girls, united by their outcast status and the telling ink of a butterfly. These are the hor tiap, or the all-female members of real-life secret society Red Butterfly.

And, suddenly, Adeline finds herself in the trenches with the burly Tian, the wily and suspicious Pek Mun and the diplomatic Christina, trying to thread a needle as to how far they should give in to the fire.

Deity Madame Red Butterfly is a voiceless but eager presence. Rival Three Steel gang appears to be taking advantage of the chaos to consolidate territory while a bigger conspiracy threatening the foundations of the old order provides a driving mystery.

There is plenty that is fresh about When They Burned The Butterfly. Its restrained use of magic is almost intelligible without the fantasy tag, manifesting only in a patch of impenetrable skin here and unnatural beauty elsewhere, never flight or dragon-riding sorcery.

But this groundedness comes also because secret societies, with their obscure rituals surrounding tattoo ink and blood, are a black hole into which readers can let their imagination run wild while everything above ground maintains its shape of rationality.

The two worlds, inevitably class-based, almost never collide. When they do, events manifest dramatically, but are at the same time eminently explainable. The historical disaster of the Bukit Ho Swee fire Lee smartly uses as a precedent of what is possible – a promise she finally makes good on.

For a book published overseas, Lee’s vision keeps to a stubborn geographical specificity. In just a few lines, Thian Hock Keng Temple, Sri Mariamman and Masjid Jamae get nods the prose wears lightly on its sleeves.

Vivid confrontations rage on in hedonist entertainment centre Bugis Street, and the deserted New World Amusement Park. Or even the now-disappeared island in the Singapore River, Pulau Saigon, frequented only by godown workers and so becoming the perfect site for gothic horror.

The centring of the Red Butterflies, naturally, lets Lee make this a story of and about girls and women. Even when pitching them against one another, she is really allowing different versions of girlhood to exist.

Little shifts in dynamic where they fight for supremacy in the gang are a pleasure, though sometimes calculations are overexplained. And there is perhaps an underreaction on Adeline’s part to realising the true cause of a loved one’s death, which might have required a little dwelling upon before she soldiers on.

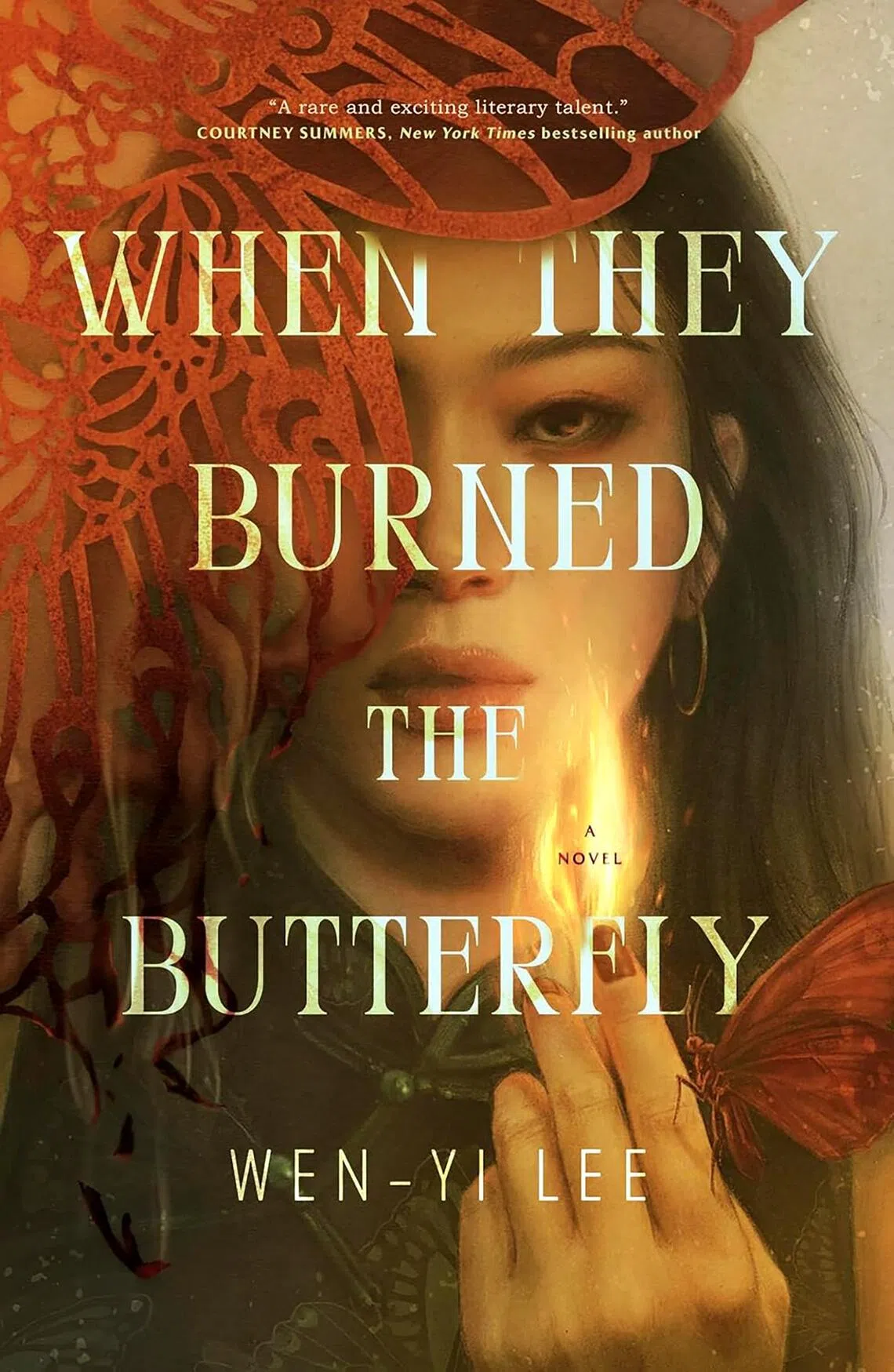

When They Burned The Butterfly by Wen-yi Lee.

PHOTO: TOR BOOKS

Bravely among Singaporean authors, Lee does not shy away from bodily attraction and sex. It is the same willingness to push taboo that she uses in her rendering of violence and there is gore to feed the mature imagination here, both creating a welcome raciness in SingLit’s sterilised oeuvre.

Perhaps the most difficult high-wire balancing act Lee succeeds in achieving are those moments of understanding of how ganghood can feel like everything for participants and yet at the same time mean nothing for the rest.

Adeline and her friends are self-aware enough to know this. Yet, their inability to let go also feels compelling as a choice. There is, for this reviewer, no analogue for such a sensitive literary appreciation of the empowering tragedy of gangs in the Singapore context.

In a quick cutaway, Lee, like so many of her literary forbears, pays mandatory tribute to the Merlion, then turns away to add timbre to the old magic. She asks rhetorically – “What was blood to a bright future? What were old gods to the better world?” – even as she whisks secular, glass-and-steel Singapore back to its seedy past and its migrant roots, gods brought here over sea.

The kicker comes after: “To those who remained, they were still a power to be used.” With a sequel already in the works, this sounds tantalisingly like both warning and promise.

Rating: ★★★★☆

If you like this, read: Neon Yang’s The Tensorate Series: The Black Tides Of Heaven (Tor, 2017, $24.25). Also by a Singapore author, this is an equally high-profile Asian-inspired queer fantasy series, though less tied to Singapore. It has earned nominations for almost every major science fiction and fantasy award.