‘Nobody elected tech leaders’: Microsoft founder Bill Gates talks politics, Elon Musk and AI

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

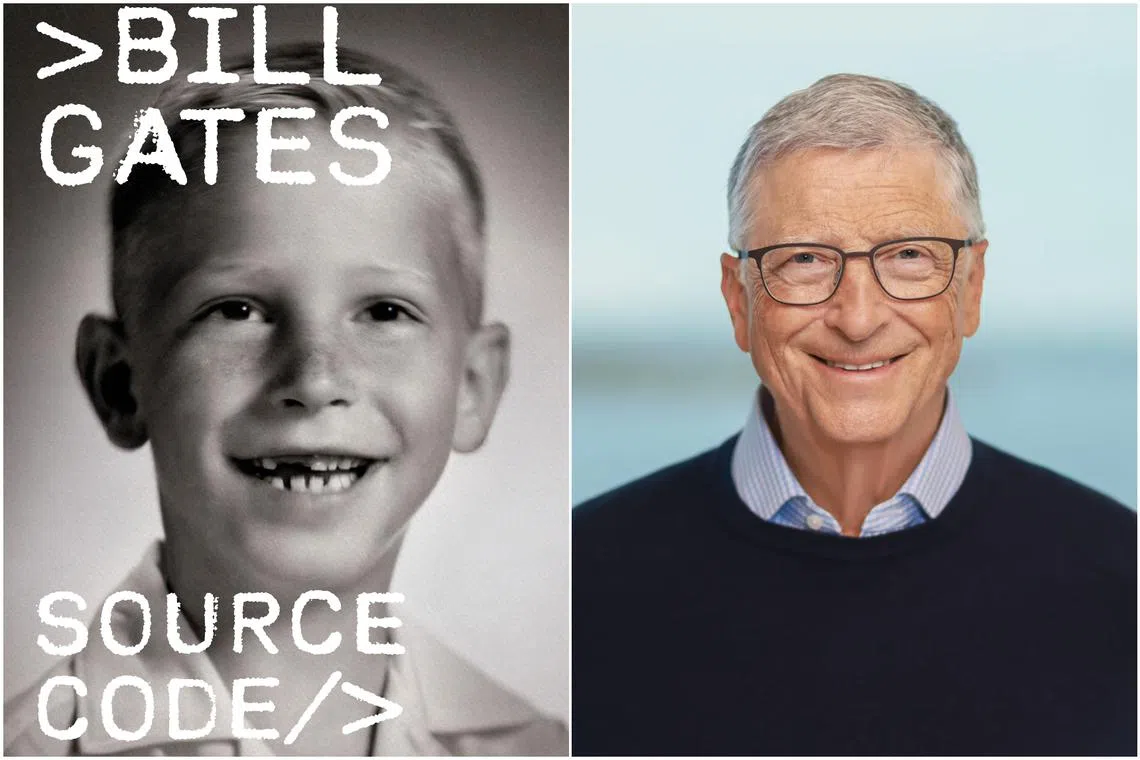

Mr Bill Gates is launching Source Code: My Beginnings, his memoir spanning his childhood and the 1970s.

PHOTOS: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE, GATES VENTURES

SINGAPORE – As the 69-year-old Bill Gates talked, he rocked.

This physical quirk has been noted by many who have interacted with the famous co-founder of Microsoft. Now, witnessing it over a video call, this metronomic movement is so genial, it takes only some getting used to.

Rather than signalling impatience, it appears to both abet and smooth over the ticking of Mr Gates’ mind – which, at the moment, he is applying to diagnosing himself with Asperger’s.

He told a select group of Asia publications, including The Straits Times, Japan’s Asahi Shimbun, Korea’s JoongAng Daily and China’s Caixin Global, on Jan 8: “My ability (as a kid) to write a 200-page report on Delaware, or to read more science fiction books than anyone I knew, my social skills being slower to develop and less natural than the average kid – (they were) strange enough to have a teacher say I should be pushed back in school, and another to say I should be pushed ahead.”

Mr Gates is launching Source Code: My Beginnings, his memoir spanning his childhood and the 1970s, when he made the defining decision to drop out of Harvard University and start Microsoft.

It is the first entry of an envisioned trilogy. The other two will cover his Microsoft and philanthropy days.

In this first book of teenage shenanigans, he describes many occasions where he spent days hardly eating and coding non-stop – “The math department’s equivalent of those nude models (for art class) was this computer terminal”.

At a time when the computer laboratory had to be bitingly cold to keep the machine cool, he wore a winter jacket and slept curled up next to it for warmth.

“My parents ended up doing a lot of things right, even though there was no guideline,” Mr Gates says of his father Bill, a prominent lawyer in Seattle, and mother Mary, a pioneering businesswoman in a pantsuit who served on the boards of multiple financial and non-profit companies.

They sent him for counselling after one particularly egregious moment when he snapped at his mother: “I’m thinking! Don’t you ever think?”

They themselves enrolled in parent effectiveness training at church, eventually granting their oddball prodigy son a long leash while remaining supportive.

Mr Gates says: “There are therapies and medicine now directed to that. I don’t know whether that would have been better for me or not. For any parent who has a kid who is a little unusual, the fact that it can, at the end, work out, hopefully makes them feel hopeful.”

The hour-long session with Mr Gates took place with an elephant in the room. In January, Tesla founder and X owner Elon Musk had just been appointed by US President Donald Trump to lead the Department of Government Efficiency

The richest man in the world – a position Mr Gates once monopolised – was also daily tweeting his support for far-right European politicians

What does Mr Gates think of those at the helm of tech companies playing such outsized roles in world politics and government?

Mr Gates, who has since the interview grown increasingly critical of Mr Musk, adroitly steers his answer to his own conversations with the American administration on artificial intelligence (AI) and global health.

But he concedes: “You could take this too far. Nobody elected tech leaders.”

Though Mr Musk is grabbing the headlines, he does not have a monopoly on access. Mr Gates himself had a three-hour dinner with Mr Trump.

“We should wait and see. We have really good antitrust laws. You know, it is a democracy,” Mr Gates says. “The fact that politicians meet them and listen to them, I think that’s fine.”

He is harsher in a later interview with The Times of London newspaper: “We can all overreach... If someone is super-smart, and he is, they should think how they can help out. But this is populist stirring.”

In this moment, he still notes that Mr Musk is a member of The Giving Pledge. “I hope some day he will focus on that.”

Probably the largest beneficiary of the first tech revolution – the advent of the microchip that made personal computers possible – Mr Gates is today worth a whopping US$107.4 billion (S$147 billion).

Once a firm believer in the “unadulterated goodness” of the tool that made him, he says he was disabused of this notion when social networking became popular: “Not to say that criminals couldn’t use a spreadsheet, but once you have social networks, there were enclaves for people to share crazy ideas.”

He will be the first to admit his fortune of being born at just the right time when a few young people could take on the biggest computer companies. But he had also been waiting for AI his whole career.

It was not until ChatGPT 4 in 2023 that AI has been able to “read and write in a profound sense”.

The Gates Foundation is using the tool in its drug discovery work, “accelerating our results pretty substantially”.

He describes himself as a “constitutionally and fairly optimistic and risk-taking person”. “I fully admit that just because we’re smarter, we can still make big mistakes. But still, this is the best time in the world to be born.”

It is not a view popular with young people coming of age in a world besieged by wars and the climate crisis. But for Mr Gates, human ingenuity always prevails. “The net benefit is there for AI and we can minimise some of those negatives if we’re smart about it. If we don’t focus on solving the problems, it won’t get better the way that it should.”

Despite Mr Gates’ first 25 years being “about as ideal as at least I could imagine”, Source Code touches on a core tragedy: The death of his best friend, Kent Evans, in a hiking accident at 17, a catalysing incident that pushed him closer to Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

“For a few months, I didn’t do much at all,” recalls Mr Gates, who has not said much about the event in public. “I haven’t had anybody around me die other than a grandparent and a great-grandparent, so I was completely shocked.”

He adds before quickly veering from the topic: “As I thought about Kent’s parents, I thought they will never have this son who would have worked with me and been quite amazing. I stayed in touch with his family. I ran into his father a couple of years ago, and we talked about those days.”

His is a story “driven by luck, (of a boy) obsessed by something to really go out and take the risk”. “I’m not counselling people to drop out of school. I don’t think that was the key.”

He bristles against the label of dropout: “It’s kind of weird. I watch more courses and read more books.”

He has earned the right to assess himself: “I’m actually one of the most enthusiastic students that ever lived.”

Source Code: My Beginnings by Bill Gates ($45.13, 2025, Alfred A. Knopf) is available at major bookstores.