Has the Aichi Triennale cracked the secret to a successful contemporary arts festival?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Bassim Al Shaker's Sky Revolution at the Aichi Triennale, curated by Emirati artistic director Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi.

PHOTO: AICHI TRIENNALE ORGANISING COMMITTEE

Follow topic:

- Aichi Triennale uses contemporary art to boost the economy, but faces challenges balancing artistic freedom with political and community sensitivities.

- Artistic director Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi champions artists from the global south. She ensures a safe space for discussing challenging issues like colonisation and exploitation.

- Aichi learnt from its 2019 controversy to prioritise open dialogue with artists, volunteers and the community. It focuses on long-term growth and community trust.

AI generated

AICHI, Japan – Contemporary art often challenges conventions and courts controversy.

But since the 1990s, countries have latched on to contemporary arts festivals as a means of powering economic growth and urban renewal. Singapore, too, jumped on the biennale bandwagon in 2006. The event returns from Oct 31 to March 29, 2026.

But Japan seems to have cracked the code for a winning formula, with biennales and triennales generating billion-yen revenues in tourism while rejuvenating both urban and rural communities.

The Aichi Triennale, which opened on Sept 12, is one of at least 10 such large-scale contemporary arts events crowding Japan’s arts calendar. But it has also experienced the pitfalls of trying to harness the unpredictable energies of contemporary art to institutional goals often dictated by organisations beholden to political rather than artistic considerations.

The 2025 triennale drew a small group of people using the event to protest the Aichi-Israel Matching Program, which links the prefecture’s companies with Israeli start-ups. At the Aichi Arts Center after the opening ceremony, a couple of protesters also managed to sneak in to unfurl a banner and shout slogans including “Free Palestine” to a crowd of disconcerted invited guests.

The triennale’s Emirati artistic director Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi makes no bones about her support for Palestine, speaking of the “live genocide” and “ethnic cleansing” both at the media conference and the opening ceremony

Genial and soft-spoken, Ms Hoor, who speaks five languages including Japanese, tells The Straits Times that she has been “outspoken about Palestine since I was a baby”, before whipping out her mobile phone to share a photo of herself as a toddler draped in a keffiyeh.

“I have a platform, I have the mic and I’m going to speak out. Otherwise, what am I going to say on stage that matters?” she adds.

She is no mere dilettante. She studied to be a painter at London’s Slade School of Fine Art and holds a master’s in curating contemporary art from the Royal College of Art, London. And she is making her mark as a curator who champions voices of the global south in an arena still dominated by white voices.

Ms Hoor, founder of the Sharjah Art Foundation and director of the well-regarded Sharjah Biennial

In a contested world where every space can, and has, become a battlefield, literal or metaphorical, Ms Hoor has been dogged in carving out safe spaces for artists to contribute to fraught conversations about everything from colonisation and exploitation to gender and race.

At Aichi, Basel Abbas, Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Baraari, who are artists of Palestinian extraction, opened the festival with a late-night party at Nagoya’s Club Mago. The triennale’s theme, A Time Between Ashes And Roses, is inspired by contemporary Arab poet Adonis’ work, which was written in the wake of the 1967 Six-Day War.

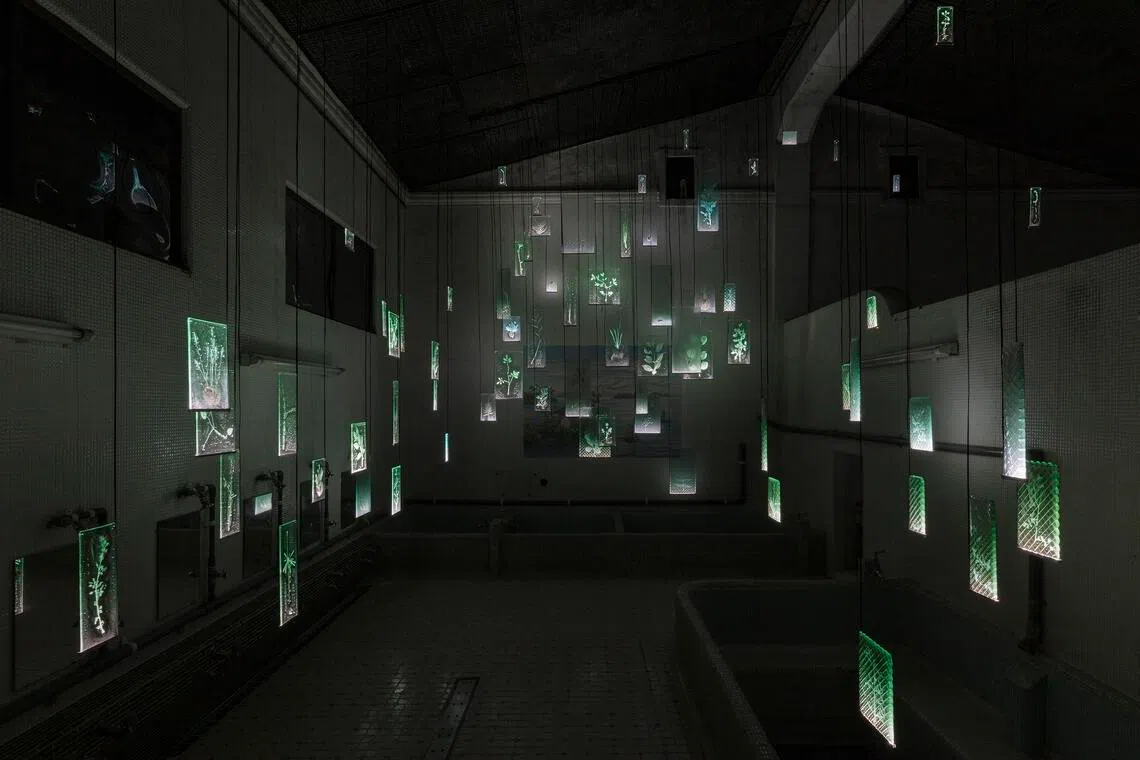

An installation at Aichi Arts Center.

ST PHOTO: ONG SOR FERN

Ms Hoor also gives airtime to Latin American artists and highlights especially work from women of colour. At Aichi, her interest in indigenous voices led her to programme artist Mayunkiki, who is Ainu, an indigenous ethnic group in northern Japan and south-eastern Russia.

These interests are a constant in her curation, evident too in her programming of the Sharjah Biennial.

Ms Hoor is quick to emphasise that the triennale’s organisers have given her free rein. “It’s been really great here. I didn’t get a single ‘no, we can’t talk about this’ or ‘we can’t show this because…’. They’re very much interested in creating a safe space for artists.”

Aichi’s tolerance has been hard-earned, notes curator Iida Shihoko, who has been involved in several Aichi Triennales, including 2019’s controversial edition.

That year, the triennale shut down a section featuring South Korean artists Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung’s Statue Of Peace (2011), a sculpture of a comfort woman, and Japanese artist Oura Nobuyuki’s 20-minute film, Holding Perspective: Part 2, which had a scene where a photograph of Emperor Hirohito was burned to ashes.

These works attracted the ire of right-wing conservatives who bombarded the triennale office with angry phone calls and threats on social media.

Organisers responded by closing part of the exhibition, citing “risk management”. The move drew flak from international luminaries such as artist Ai Weiwei and writer Salman Rushdie, while Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs cut its subsidy for the triennale in the wake of the brouhaha.

The Singapore Biennale has run into similar challenges over the years when trying to balance edgy artmaking with community sensibilities.

In 2011, for example, the Singapore Art Museum removed pornographic magazines from Simon Fujiwara’s installation, Welcome To The Hotel Munber.

Singapore reacted in a typically Singaporean fashion to the uproar: A consultative committee was set up to advise curators and avoid further censorship clashes.

Japanese artist Kato Izumi’s work at the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum, shown as part of the Aichi Triennale.

ST PHOTO: ONG SOR FERN

There are useful guiding principles Singapore can pick up from Aichi’s strategies. The organisers seem to be doubling down with the appointment of Ms Hoor in 2023, citing the desire for “fresh perspectives”.

Ms Shihoko says the 2019 affair was “not a great experience” for the curators and organisers. “But it was important and super significant for us as an organisation. Precisely because of that, we learnt a lot. It is important how we can heal ourselves and recover.”

What the team learnt was to talk through everything with everyone.

To hold space for difficult conversations, Ms Hoor says, context and understanding are critical.

“You have to understand where you’re showing, how you’re going to approach it. You need to know, is this going to be accepted. How can you explain it in a way that the community would understand and be able to accept it? And to ensure that any issues that happen, if artists aren’t happy about something, we discuss.”

Ms Shihoko agrees that conversations and transparency are important components to bridging the gap between artists and audiences. “It’s always important as a curator to be with artists, to talk with artists. It is equally important to be with our audiences including volunteer staff.”

The Aichi Triennale inherited nearly 10,000 volunteers from the 2005 World Expo in Aichi. Ms Shihoko says half-jokingly that some of these volunteers are “professional art viewers”, having seen more triennales than some of the curators. They are a critical part of the triennale’s logistics and outreach, helping to guide at exhibitions as well as learning centres.

Elena Damiani's Relieve III at the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum.

PHOTO: AICHI TRIENNALE ORGANISING COMMITTEE

Both Ms Hoor and Ms Shihoko say a long-term perspective is critical to ensuring a biennale or triennale’s success. The Sharjah Biennial was founded in 1993 and has hit its stride only in the past decade. Ms Shihoko says the Aichi Triennale, founded in 2010, can be assessed only after three more editions.

This long timeframe also allows the audience to mature along with the triennale, she adds. “It’s very important for us working with community and audiences. We have grown up together.”

Similarly, from her experience with Sharjah, Ms Hoor says: “It takes 20 years to see a difference, not only with tourists, but also with local visitors. Because you have a whole generation that grew up with the biennial. A lot of people who come are those who used to do workshops as children, or people who work with us.”

This kind of community trust can accrue as interest only after years of investment, and Ms Hoor notes it takes hard work to build.

A defining ingredient for a successful event, she believes, is growing strong roots in the community and city. “A biennale always has to connect to the city in any way possible.

“Sometimes people forget, they think a biennale is just a travelling show. But it’s about the city you’re in, so you have to make a connection, either through artist research or sites. For the sites, it is not just superficial engagement. It really needs to be in conversation with the owners of the site.”

Sasaki Rui's Unforgettable Residues at the Aichi Triennale.

PHOTO: AICHI TRIENNALE ORGANISING COMMITTEE

Bravery, too, is another key ingredient. “Bringing new voices, new artists that never would have had this opportunity. Because biennales are also a place for experimental work.”

She reasserts the first principles for a successful contemporary arts festival. “Your purpose and vision have to be the people, the place, the artists, the community because that’s your audience throughout the whole two, three months of the festival. The people flying in and out, it’s great, but it’s not your core audience.”

Both curators are reluctant to measure success in hard numbers, although the Aichi Triennale attracted 675,939 visitors in 2019, and the prefecture’s cultural affairs department estimates that the event generates about 10 billion yen (S$87 million) for the regional economy.

Ms Hoor prefers to measure success in unquantifiable ways.

“Maybe hearing from the audiences what they got out of it and also hearing from the team, how happy and satisfied they are with the work that they put in,” she says.

“It was also just so nice to see people engaging with the art.”