Golden Mile Complex designer Tay Kheng Soon: Don’t be duped by idea of global city

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

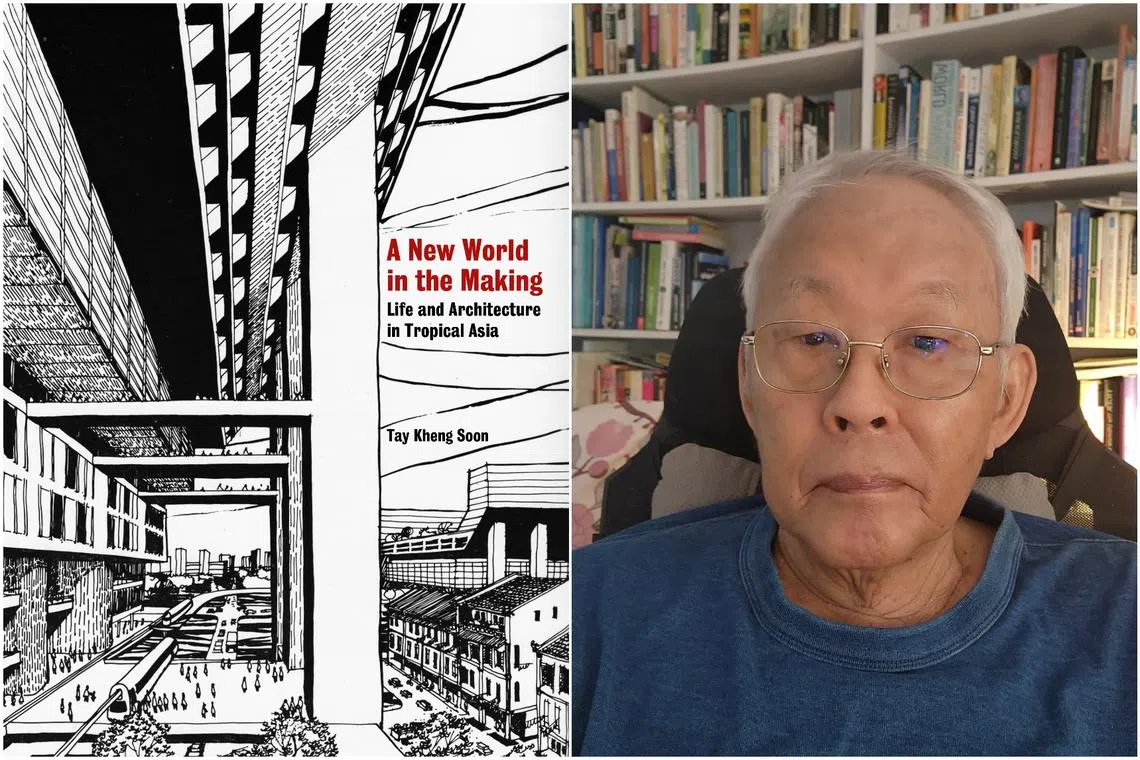

A New World In The Making: Life And Architecture In Tropical Asia is a new, shorter offering by NUS Press, coming in at 274 pages.

PHOTOS: RIDGE BOOKS, TAY KHENG SOON

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – In 1968, architect Tay Kheng Soon received a call from then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s office. He had impressed with a paper he authored on housing and nation building, and Mr Lee, through his adviser George Thompson, wished to see him.

Ushered through the doors of City Hall, Tay was struck by Mr Lee’s “height and ruddy complexion”. Mr Lee, however, had no time for niceties, immediately beginning a thrust-and-parry with Tay on the role of Malay kampungs in modern Singapore.

The content of the discussion seemed to hardly matter, recalls Tay in his new book. “The man was sizing me up. But beyond argument, I also felt the weight of his overbearing presence. It was palpable. You could not prevail against this colossus of a man.”

A New World In The Making: Life And Architecture In Tropical Asia is a whittled-down version of Tay’s 2021 Big Thinking On A Small Island: The Collected Writings & Ruminations Of Tay Kheng Soon, which was edited by Kevin Tan and Alvin Tan and which ran to over 700 pages. “Unreadable”, muses Tay today.

This new, shorter offering by NUS Press comes at a more manageable 274 pages. Like its predecessor, it contains a short memoir written by Tay, as well as a compilation of his lectures, conference papers and proposals written in the course of his storied career, which includes the design of Brutalist icons such as Golden Mile Complex

The meeting with Mr Lee – quickly dealt with in the edited text – was an inflection point in Tay’s life. Tay, still sharp and forceful at 83, believes he was being auditioned to be Mr Lee’s planning adviser – a position later given to Dr Liu Thai Ker.

Soon after, he was asked to serve as a People’s Action Party candidate, which he turned down. By 1975, he had had high-profile run-ins with the Ministry of National Development and the Housing Board (HDB), organised a protest against the Vietnam War and left Singapore, expelled by the co-founders of his architecture firm Design Partnership, known today as DP Architects.

Asked if he regrets the more brambled path he chose, Tay says: “No, there is no regret. I cannot be under anybody’s thumb.”

After 10 years of living in Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia and designing low-cost housing there, he made his way back as an associate professor at the National University of Singapore and the president of the Singapore Institute Of Architects from 1990 to 1993. He says: “I was robust enough to take whatever situation and make the best of it.”

Tay’s ideas, abundant in the book, are radical reimaginations of Singapore’s urban development. One of his first disagreements with the authorities was over high-rise flats, which he thought should make way for a low-rise, high-density alternative.

The Singapore Planning And Urban Research Group (Spur), which he helped form in 1965, also got into a spat with HDB in 1967 over the construction of Collyer Quay’s 12-lane coastal superhighway, which Spur argued harmed the environment and was being planned without sufficient public consultation.

In recent years, he is best known for his “rubanisation”, a categorical rethink of cities’ divisions between the urban and the countryside. Within this framework, Singapore is the leader of the region, more consciously re-investing in surrounding rural areas – a proposal he says he has discussed with senior officials in Temasek.

He believes Singapore’s prospects lie in a more economically and culturally strong region. This is, in some ways, a return to the Malayan identity ideal torn asunder when Singapore and Malaysia separated in 1965.

“The younger generation has been duped into this idea of a global city,” he says. “We look upon the region as backward and we sneer at them. We see it in narrow, simplistic terms. Chinese and the West forward. Malay backward. We can’t survive if we can’t get along with our neighbours.”

Ever engaged, Tay has continued to innovate, proposing foreign worker dormitories that offer individual rooms and toilets and an Indo-Pacific Cultural Centre next to the casinos at Marina Bay to celebrate Singapore’s regional heritage.

The “rambunctious pioneering spirit” of his generation is all but gone, he laments, with “fear becoming a major condition of life and no challenging of conventional ideas”.

Naturally, his most scathing comments are reserved for Singapore’s architecture, which he describes as “obiang” – a bad taste apeing of the West, and a desperation to be superficially different that reflects a lack of deep thinking.

“We want to show off, but there’s no fundamental philosophy and regional appreciation,” he charges. Referring to black buildings that are so common to the industrial aesthetic, he adds: “Buildings painted black in our hot tropical climate is a crime.”

The belated appreciation of Golden Mile Complex and People’s Park Complex has lent his voice more popular influence. For him, architecture must balance the profit interest of the developer, practical concerns like how people move within the building, and a host of historical, environment and aesthetic concerns.

He once spent six months getting to know a client before sketching a design for his house in 10 minutes.

“It cannot be just transactional,” he says. “That is a sell-out. It must be a dialogue. It’s understanding the design problem from the inside of the problem.”

Architecture, for him, is also a tool for decolonisation. “It is sickening and a total slave mentality if it is completely Westernised. Not just copy and adapt, but inspire and contradict. Creativity emerges out of that.”

A New World In The Making: Life And Architecture In Tropical Asia ($34.50) by Tay Kheng Soon is available on Amazon SG ( amzn.to/47AaIDi