Future of HDB flats: A delicate balancing act, says sociologist Chua Beng Huat

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

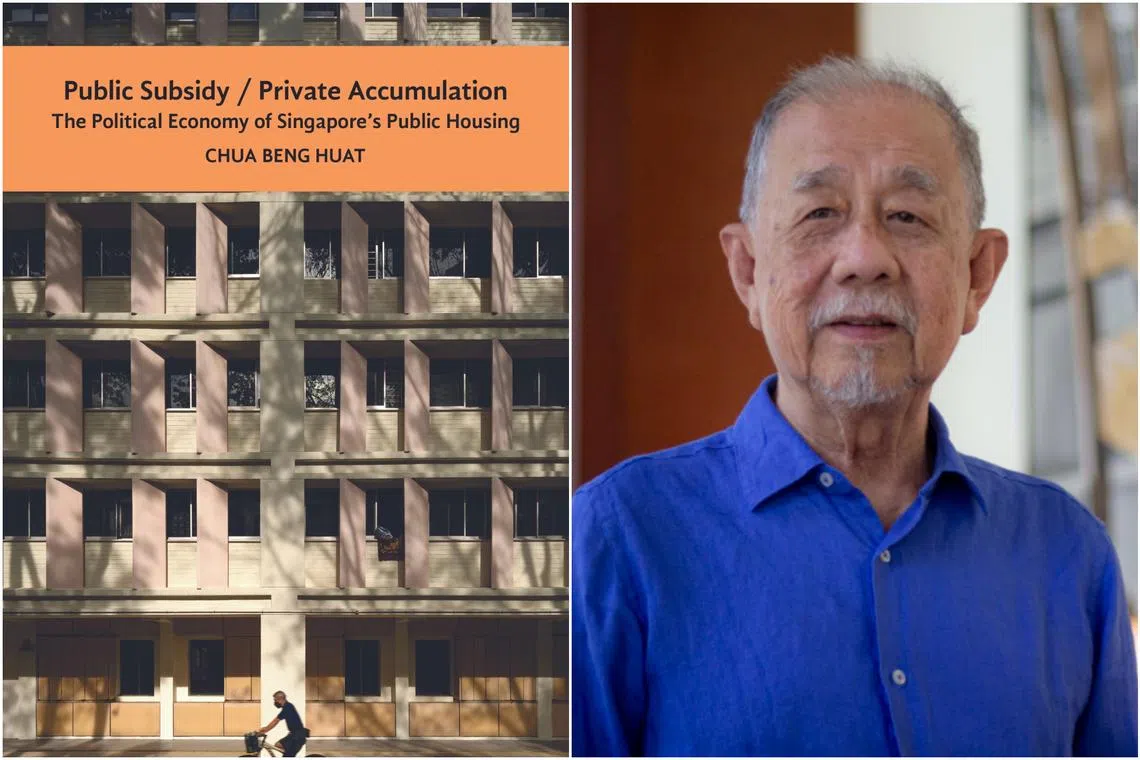

Sociologist Chua Beng Huat has written Public Subsidy/Private Accumulation: The Political Economy Of Singapore’s Public Housing.

PHOTOS: NUS PRESS

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Housing may be one of the most clamorous issues in Singapore, but despite recurring calls for the Government to curb runaway prices for young couples buying their first flat, it has arguably not intervened aggressively enough.

This is because it cannot, without affecting the nest eggs of the vast majority of older home owners, according to sociologist Chua Beng Huat’s new book. He argues that the contradiction of Housing Board (HDB) flats as both public good and financial asset lies at the heart of an increasingly intricate balancing act for the Government, which cannot afford to let the value of flats plummet after so much of its citizens’ savings have been sunk into their home purchase.

Help for new entrants is limited mostly to “temporary and mild” cooling measures and perpetual cash grants, “a strategy with no potential endpoint”, he writes in Public Subsidy/Private Accumulation: The Political Economy Of Singapore’s Public Housing, published in 2024.

The thrust of his book ties the HDB system with the political legitimacy it confers on the incumbent Government. Chua says this makes radical reform not only “practically impossible”, but also “conceptually inconceivable”.

Frustrations over housing have cost the People’s Action Party votes in the past, from the defeat at the 1981 Anson by-election to the losses it sustained in the 2011 General Election, when skyrocketing flat prices were attributed to an influx of new residents, he says.

“For the amount of subsidies that the Government has given, it has actually received a huge political return,” says Chua, 78, currently Professor Emeritus in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at the National University of Singapore (NUS), in an interview with The Straits Times.

“There’s quite a lot of gratitude about being able to own a flat. The HDB remains synonymous with the People’s Action Party-led Government.”

Might the record number of million-dollar flats resold recently mean housing will be politicised in the upcoming general election? He thinks not, though it would have been more touchy a year ago.

“It depends on whether the opposition parties could make it an issue, but the Government has done a lot to reduce waiting time since Covid-19 and there have been cooling measures.”

In general, “we actually have been able to maintain affordability really well”, he says. “If you’re buying within your income bracket, it’s about 25 to 30 per cent of your monthly income, which is practically global standard. At this point, I don’t think the opposition parties have much ammunition.”

Dressed in a nondescript T-shirt and slacks for the interview at a Novena foodcourt, Chua has been a lifelong maverick. After he is given a thumbs up by the cashier at the drink stall for ordering a cold drink, he mutters: “I don’t know why they do that – people think because you are old, you cannot drink cold drinks or something.”

One of the country’s foremost experts on public housing, he now teaches an undergraduate course on housing and social inequality in the urban studies programme at the Yale-NUS College. He once headed NUS’ Department of Sociology and was provost chair at its Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. In the early 1980s, he spent three years as director of the social research unit at HDB.

The PhD graduate from York University in Toronto, Canada, joined the Department of Sociology at NUS in 1985, and has been venerated by his students for his acuity of thought and facility of expression. There is even a Facebook fan page dedicated to him, with a tongue-in-cheek name: “If I Weren’t Christian, Chua Beng Huat Would Be My God”.

In this analysis of housing in Singapore, he flags some structural problems of HDB flats that he says are growing more visible by the day.

Apart from the “endemic balancing act” between flats’ affordability and maintaining their value – enmeshed within a resale market that HDB cannot completely control – there is also the problem that housing could become one of the biggest factors that exacerbate wealth and generational inequality, he says.

Though profiting from the buy-sell-repurchase cycle is in theory open to all home owners, only a third of them have been able to capitalise on this, while two-thirds have not been able to – or have opted not to – trade in their one and only flat.

In addition, 5 to 6 per cent of the population cannot afford to own homes. They are subjected to strict government rental controls in small, overcrowded flats, due to the belief that this will encourage renters to work towards owning their own place, he adds.

Chua says: “The profit motive has become much more pronounced, particularly because of the million-dollar flats. The younger generation is more calculative about making profit from HDB, but in practice, only those with higher income among the residents are able to upgrade.”

Recent efforts to reduce the “lottery effect” of HDB flats – where those who can afford flats in more central and more connected estates will benefit disproportionately upon resale – through a reclassification of Build-To-Order flats from mature and non-mature estates to that for Standard, Plus and Prime might not be sufficient, he feels.

“I don’t think the inequality issue will ever be solved,” he says, though he remains sanguine. “The Government will keep watching and make sure it doesn’t become a serious social problem.”

Another issue is that public homeownership in Singapore comes with a 99-year lease, an important caveat that some gloss over.

For older home owners, a shorter time left on their 99-year lease and ageing amenities result in a devaluing of their retirement savings. There is a time element to this, with flats bought around the 1970s drawing closer to the end of their 99-year-lease in 2069 and the 2070s.

Chua cites how, in 2022, four blocks in Ang Mo Kio with 56 years left on their lease that were picked for redevelopment had a professionally assessed compensation that fell below the price of equivalent new flats in the same neighbourhood. This meant that affected residents would have to cough up as much as $100,000 more for an equivalent flat, or downsize. They were later offered other options, such as buying a same-sized flat with a 50-year lease.

“When the lease gets shorter and shorter, of course the values decline. You can see the future. Since everybody is encouraged to invest his or her retirement money in the house, you have to figure out some way for people to recover the capital, especially for those in the lower-income group,” Chua says.

Over the years, policies have been implemented to tackle this, such as a lease buyback scheme and bonuses to encourage seniors to sell their flats and downsize. There is so far no solution, though, to the fundamental problem of the 99-year lease.

As the country develops, Chua anticipates there will also be increasing demand from those who face more restrictions in the current system, including single mothers, singles and people who are gay, to be better included. This is a political debate the Government must reckon with, and not a matter of supply, he adds.

There is nothing to do now, though, but to keep “patching” these problems as and when they surface. Chua compares it to a computer operating system. “You can develop a whole new one, and that will take a lot of time and will cost.”

Even introducing something like a shorter lease for purchase would change the market value of existing flats. And that is not to mention the unintended consequences that would result, such as creating an administrative headache for the HDB – it would have to buy back some 20,000 flats every year – while leaving much more money in people’s Central Provident Fund accounts, he says.

“I think we can keep patching, because what do you do with the existing system? You have to say it starts at year zero. It will take a very long time, and in the meantime, we don’t know what the market effect will be.”

Public Subsidy/Private Accumulation: The Political Economy Of Singapore’s Public Housing by Chua Beng Huat is published by NUS Press and available for $26.17 at Amazon SG (

amzn.to/3W17GUB

).

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.