Enigmas is Simon Tay’s love letter to his father, Singapore’s first spy chief

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

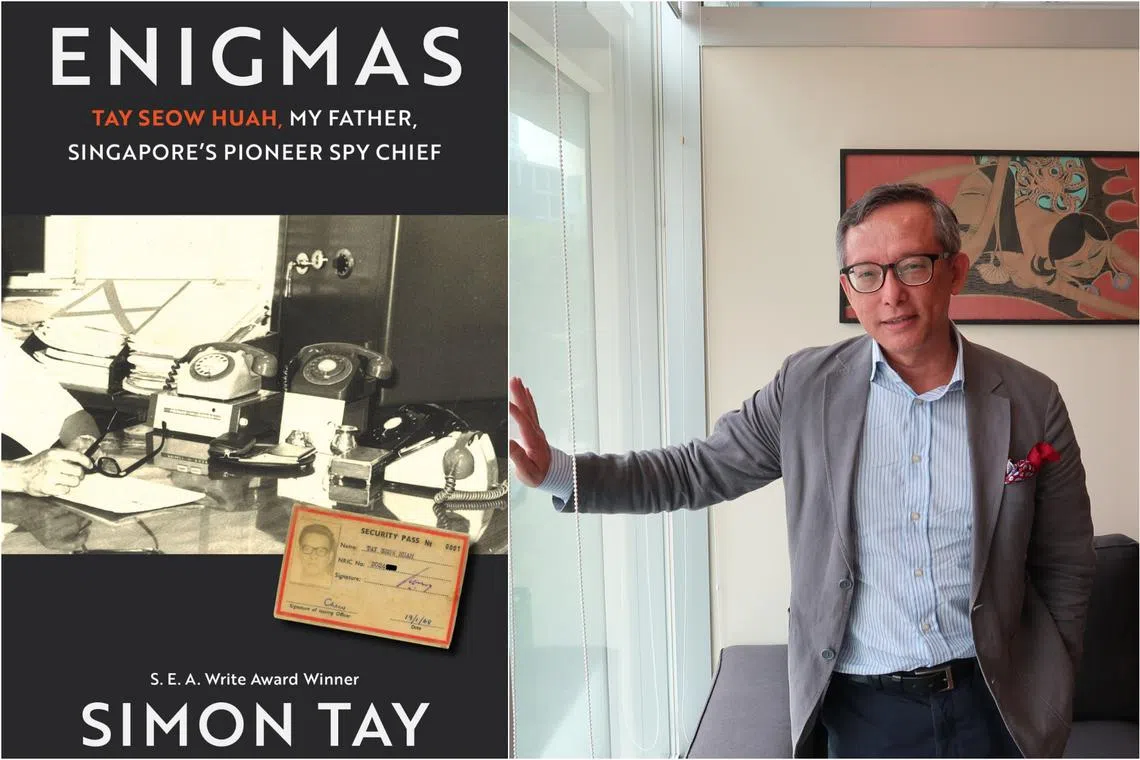

Author Simon Tay is behind Enigmas: Tay Seow Huah, My Father, Singapore’s Pioneer Spy Chief.

PHOTOS: LANDMARK BOOKS, COURTESY OF SIMON TAY

SINGAPORE – Magni nominis umbra, or in the shadow of his greatness.

This Latin dictum was the motto of King Edward VII School in Malaysia’s Taiping, where Simon Tay’s father, Tay Seow Huah, studied in the 1940s.

Originally referring to humility in God’s glory, it equally applies to Simon’s motivations for writing Enigmas. The blend of historical, memoiristic and creative fiction elements is the product of over four decades of the author processing his father’s death in 1980, when the elder Tay was 47 and the younger just 19.

“As a son, this bears on you,” says Simon, now 63 and conscious of his own “end of life” and legacy, over Zoom. “I was writing poetry and stories which touched on various parts of my father’s life, but only now can I make some sense of it as a whole.”

This delayed reckoning is little wonder, for Seow Huah was no ordinary man.

In the book, Simon recalls how schoolteachers’ routine questions about his father’s occupation were met with a note or phone call instructing them not to probe beyond the vague epithet of “senior civil servant”.

But in Simon’s own public-facing career – as a three-term Nominated MP from 1997 to 2001, chairman of Singapore’s National Environment Agency from 2002 to 2008, and now, chairman of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs – he encountered, at every turn, people who knew his father.

Professor S. Jayakumar, his dean at National University of Singapore law school who later served as deputy prime minister, knew his father. So did Ambassador-at-Large Chan Heng Chee, Simon’s boss when he was 30; and 90-year-old esteemed poet Edwin Thumboo, who attended the March book launch at the Senior Police Officers’ Mess in Mount Pleasant Road in a wheelchair.

Seow Huah was independent Singapore’s first director of the Special Branch, which he reorganised in 1966 to become the Security and Intelligence Division (SID) and the Internal Security Department, one focusing on foreign intelligence and the other domestic.

In 1970, he reached the pinnacle of civil service, doubling as permanent secretary of the newly formed Ministry of Home Affairs.

Simon notes that as director of the Special Branch and later SID, his father always had a direct channel to founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and former deputy prime minister Goh Keng Swee, who were impressed by his previous arbitration efforts on behalf of the port authority with the port workers and unions.

Their trust in him was such that he was thrust into the spotlight during what is still probably Singapore’s most high-profile terrorist incident, helming operations and conducting daily press briefings during the bombing of the Shell oil refinery on Pulau Bukom in 1974.

The frenetic Laju incident, which grabbed global headlines and opens Enigmas, involved a nine-day stand-off after the hijacking of the ferryboat Laju in Singapore waters.

The incident may have passed from public memory, but circumstances surrounding it are “rhyming” now.

Simon says: “The attack was motivated by the desire to cripple a major oil refinery that fuelled the military effort by the United States in South Vietnam. The Red Army of Japan was involved, but there were also two Palestinians who identified themselves as being from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

“Today, there are still refineries running. We have US logistical bases. We have conflagrations in the world, including in Gaza. It’s not personal. Singapore, as long as we host multinationals, could be a target.”

But naturally, much of Seow Huah’s operations remains secret, and those looking for details of Singapore’s intelligence gathering will find themselves stymied by motherhood descriptions.

Where the book captures attention are Simon’s creative elements, connecting and sometimes guessing at people’s motives. At its best, it also fleshes out Seow Huah as a reckless “James Bond” character who loved the outdoors, swimming, motorbikes and sports cars.

There is an unverified rumour of him fighting with a church elder after his proposal to a girl of another class was rejected. At home, he brushed his tongue so hard, he choked, and often had Jaffa orange in the morning, a nod to his bringing in Israeli trainers – masquerading as “Mexicans” – to build up Singapore’s defence capabilities in the early years.

Simon says Enigmas is also about his writing, and he has created three fictional conversations between himself and his father, both frozen at age 47, in the coda – “a bending of reality”.

“I could say that I’m probably more well known than my father now. His generation is almost gone,” he adds. “Rather than in his shadow, my life has run in parallel. He served Singapore and I hope, in my own way, I have as well. Maybe that was what his example taught me.”

He is also frank about the toll on his father after he was forcibly retired from the civil service at age 42 in 1976 for medical reasons, and ended up teaching history at the University of Singapore.

Both Mr Lee and Dr Goh were not sentimental people, and “in those days, they couldn’t find that soft landing that one might have hoped for”.

Asked if his father felt betrayed by this shunting, Simon says he never once heard him voice his anger at the leaders. He was frustrated more with his own health.

“Generally, people do warn you that you need to have balance: family, friends, pursuits. Not just be your job title,” he adds.

The demands of civil service are not for everyone. Mr George Bogaars, who was director of the Special Branch in 1961, warned Simon against joining the civil service. “The pioneers did it because they had to do it. Something had to be done. If options were there, they might not have. To my knowledge, not many founding-generation senior civil servants have children in the Government.”

More attention might be paid to the many people who have contributed to Singapore, including those who have not had a book or a chapter, or been mentioned by Mr Lee, Simon adds.

It is a mistake to treat civil servants – especially permanent secretaries – as those merely doing the bidding of ministers, he says.

Someone like Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Communications Ngiam Tong Dow believed in an MRT system when a minister wanted buses.

When the Laju incident happened, Seow Huah had been an expert in the field for nine years, while Minister of Home Affairs Chua Sian Chin at the time had been in position for only two.

“The whole generation deserves to be recognised,” Simon says.

The drawback? “Some of the memories of the children might be negative, or less positive than you think,” he concedes. “The concept of fathering then was very different. We didn’t see our fathers very much because they were always busy.”

Enigmas: Tay Seow Huah, My Father, Singapore’s Pioneer Spy Chief is published by Landmark Books and available for $41.20 (

str.sg/6ma9

).