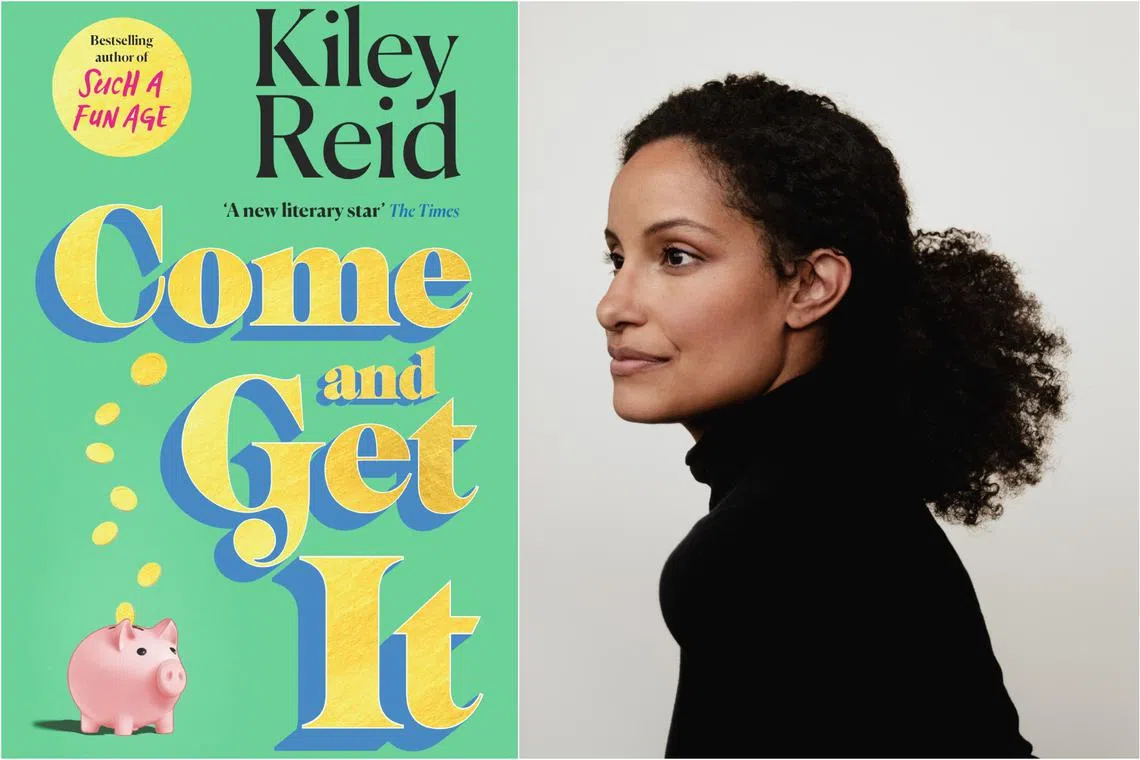

Come And Get It author Kiley Reid inspired by the young and their trends

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

American novelist Kiley Reid's latest campus novel, Come And Get It, is set in a university dormitory in Arkansas.

PHOTOS: BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING, DAVID GODDARD

SINGAPORE – Hanging out with her “very dorky theatre crew” in New York in the 2000s, American novelist Kiley Reid remembers taking bowling alley shoes and wearing them as a status symbol.

Today, the 36-year-old confesses she is out of touch with what is in vogue. When she first saw students around her all in oversized T-shirts, small shorts and Birkenstocks, she thought they might be participating in an event.

“I’m also always shocked at how many of my students wear the exact same black baby cropped top and bulky jeans,” Reid, an assistant professor of English at the University of Michigan, says over Zoom.

“While I don’t always understand it, I don’t think I’m meant to. As long as they are as kind as they have been to me, they can keep wearing whatever they want.”

This fashion talk is inspired by Reid’s latest campus novel, Come And Get It, set in a university dormitory in Arkansas and peppered throughout with the “banana” things youth say – someone being “ugly hot” is a prime example, described as “no make-up, bad attitude, goes to therapy, academia top”.

Much like Reid, a visiting professor – the endlessly cool Agatha Paul – finds herself fascinated in this foreign space with its indecipherable cues.

She begins taking an interest in the students’ relationship to money – after hearing them describe actions as “ghetto” and the “practice cheques” they are getting from their parents – and forms a relationship with a young resident adviser that turns from professional into something more taboo.

Reid, whose breakout hit Such A Fun Age (2019) explored millennial anxiety and interracial relations, says “practice cheques” is a genuine phrase she took from one of the 30 to 40 people she interviewed as part of her research.

The student said she used to receive these payouts – meant to get her used to receiving a monthly income – from her father’s dental company, and Reid is not sure if it was legal.

The 21-year-olds she talked to had vastly different savings that ranged from $2,000 to $30,000. To highlight the cultural cachet money can buy, Reid’s sketches of characters are often inventories of what they wear and own – a shorthand to their personality that is very rarely off the mark.

The author says: “I’m not super fascinated by fashion myself, but clothing evokes emotion, history, status and class very quickly, and I was interested in incorporating that into my writing. I wanted readers to feel like they are roommates with these women.

“When you first meet someone in a dorm situation, you look at their belongings.”

Reid pays attention to the subtleties of clothing. Someone dressed in a “yellow polo dress, French tips and antiquated sausage curls” was “all a bit overkill for move-in day”. Another wore black athletic shorts in a strange length – “not long and sporty, but also not cute and short”.

Asked if at her age, she finds herself caught less in these moments of superficial judgment, Reid laughs and says: “It gets worse. We get more fixed in our own ways, and our curiosity goes away a little.”

Resisting this tendency is, in part, why she writes, and Reid baulks at the idea of autofiction. “That’s one part about being a writer that I do enjoy – researching and understanding different cultures, ages, geographic locations.”

As a novel about teenagers, Come And Get It avoids much of the crassness of the genre that glamourises those with outlandish wealth.

Reid is “a fan of normal-ness”, whereas a lot of literary fiction, she says, tends to focus on the hyper-rich or the extremely low-income.

It was why she set her novel not in an Ivy League university, but in Arkansas – “a very normal state school” – where people have one or two jobs and are concerned about money, but are still able to afford rent and typically have food.

Her characters toil within these believable parameters, and all the students are tempted by the money that can be doled out by adults.

“I didn’t want the socio-economic background creating the personality of the character,” Reid says. “I wanted it to be reminiscent of real life. Money is only a contributing factor to who they are.”

She points out that Tyler, one of the students with the most social power, is one of the more working-class characters.

How does someone come to be that way without overwhelming wealth? “I’m sure there’s a mix of nature versus nurture there. Tyler’s very decided – ‘This place is great, that thing is cool.’ I have a few characters comment on the way she laughs. A beautiful laugh will take you a long way.”

On tackling an unequal same-sex relationship between white professor Agatha and young resident adviser Millie, who is black, Reid says it was important to her to portray how such a power dynamic could happen across all genders.

Though it might feel more forgivable than if Agatha were male, Reid adds: “Women are more conditioned to be kind and gentle, for better or worse. That does not mean the power goes away with sweet gestures.”

Come And Get It is Reid’s first campus novel, and she theorises that the genre’s enduring appeal can be attributed to age, it being the first time in people’s lives that they are living in a walkable community, with shared resources like the libraries and dormitories that are available to everyone.

“Colleges are as close to a socialist utopia as you can get in the United States,” she says, before warning: “But that is not to say it is not also a facade. Lift up the edges and everyone is fighting.”

Kiley Reid’s Come And Get It ($30.06) is available at Amazon SG (

amzn.to/3wpYnEH

).