Book review: Xochitl Gonzalez’s second novel a caustic story of how white men stole art history

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

American writer Xochitl Gonzalez's second novel is an examination of forgotten art histories through the story of Cuban American artist Anita de Monte.

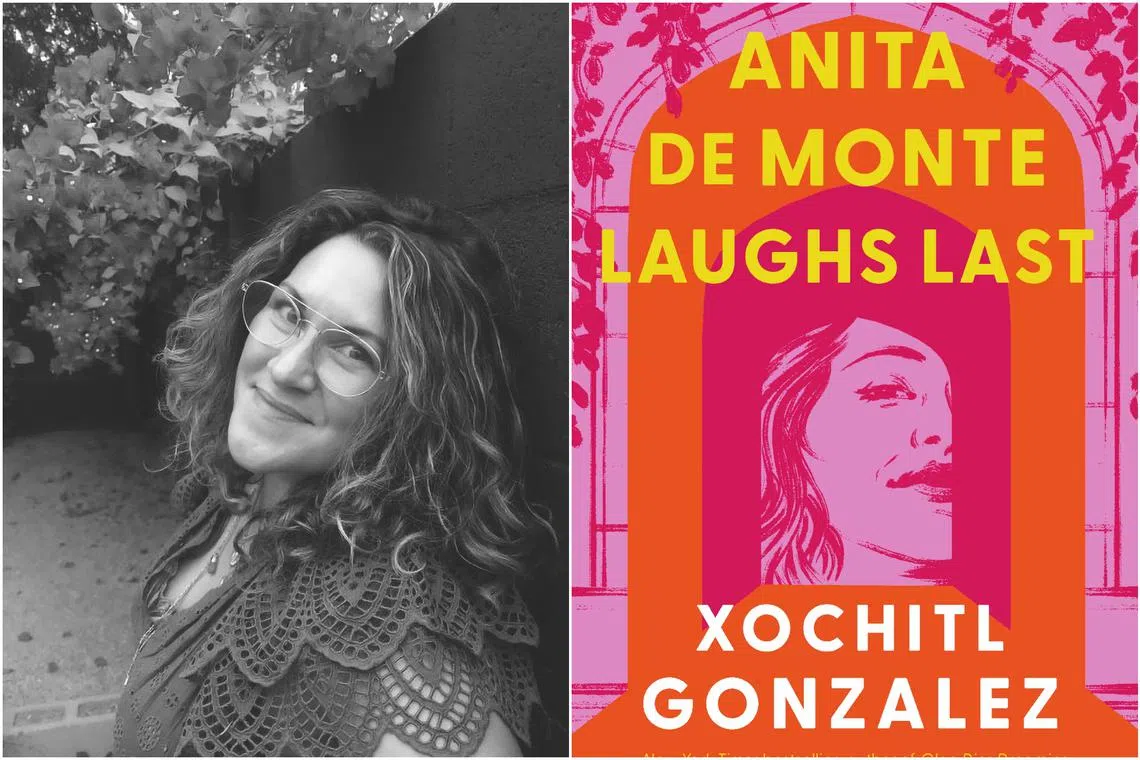

PHOTOS: MAYRA CASTILLO, BLOOMSBURY CIRCUS

Follow topic:

Anita De Monte Laughs Last

By Xochitl Gonzalez amzn.to/3LvureR

Fiction/Bloomsbury Circus/Hardcover/352 pages/$37.46/

Amazon SG (

A decade after Anita de Monte falls out the window of a New York City apartment to her death, the Cuban-American artist is a mere footnote in art history. A minor artist, a witch, a sensational story in the newspapers – few remember the name of this once Guggenheim fellow, her rising fortunes cut short.

That is, until undergraduate Raquel Toro begins to write her thesis on Anita’s former husband, the celebrated master of minimalist art, Jack Martin. Raquel, a Puerto Rican art history student at Brown University, is eager to prove she is not an “affirmative action admit”. She despises Martin’s work, but wants to win the trust of her adviser, Professor John Temple, the pre-eminent Martin scholar who can connect her to a career in the white-dominated art world of the 1990s.

American writer Xochitl Gonzalez’s sophomore novel is a caustic critique on how the art world, supposedly the vanguard of progressive ideas, never changes. Even after a decade of rising consciousness around race and gender from the 1980s to the 1990s, the art world continues to worship white male scholars, artists and gallerists, as Raquel learns while playing the prestige game.

Anita’s story is based on the story of Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta – whose husband Carl Andre, a minimalist sculptor, was acquitted of a second-degree murder charge in 1988. Gonzalez’s novel has caused some concern from Mendieta’s estate, who wants to have control over how her story is told.

The novel is a propulsive read and Gonzalez’s stylish prose reads like effortless banter, switching between multiple perspectives and capturing the rhythms of its multiple worlds – glitzy art dinners, the strait-jacketed civility of art openings, the hip-hop radio world that Raquel is equally steeped in, and the privileged frothiness of the Art History Girls whom Raquel is frenemies with.

There is even a shift from the gritty realist prose to the realm of magical realism halfway through the novel, where the fact that Anita is speaking from the world of the dead notches up the weird quotient. The book is, altogether, made of snappy prose and visually resplendent descriptions of an intriguing, if insular, art world that seems ready-made for a television adaptation.

But toggling between 1985 – the year of Anita’s death – and 1998 in which Raquel is researching this history, the timeline seems slightly implausible that things would have changed much in the art world. This implausibility, unfortunately, hampers Gonzalez’s ability to highlight the art world’s stasis and to stage a convincing tale of rediscovering a forgotten artist.

The novel’s pitting of good against evil also comes across as a bit too binaristic – the world of minimalism versus culturally informed art practice, the cruelty of privileged white men and their children versus the marginalised rest of the art world. Such easy categorisation is most glaring in the opposition of Raquel’s two mentors – the art for art’s sake Professor Temple versus Belinda Kim, an Asian-American feminist curator. Who will she choose?

In service of such easy oppositions, the novel misses a chance to mine the messy realities of both being complicit in a static system and an agent of change. It is only one side which gets the last laugh and, in this regard, the title has already given away too much.

Book rating: Three out of five stars

If you like this, read: In The Belly Of The Congo by Blaise Ndala amzn.to/3RVmQJR

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.