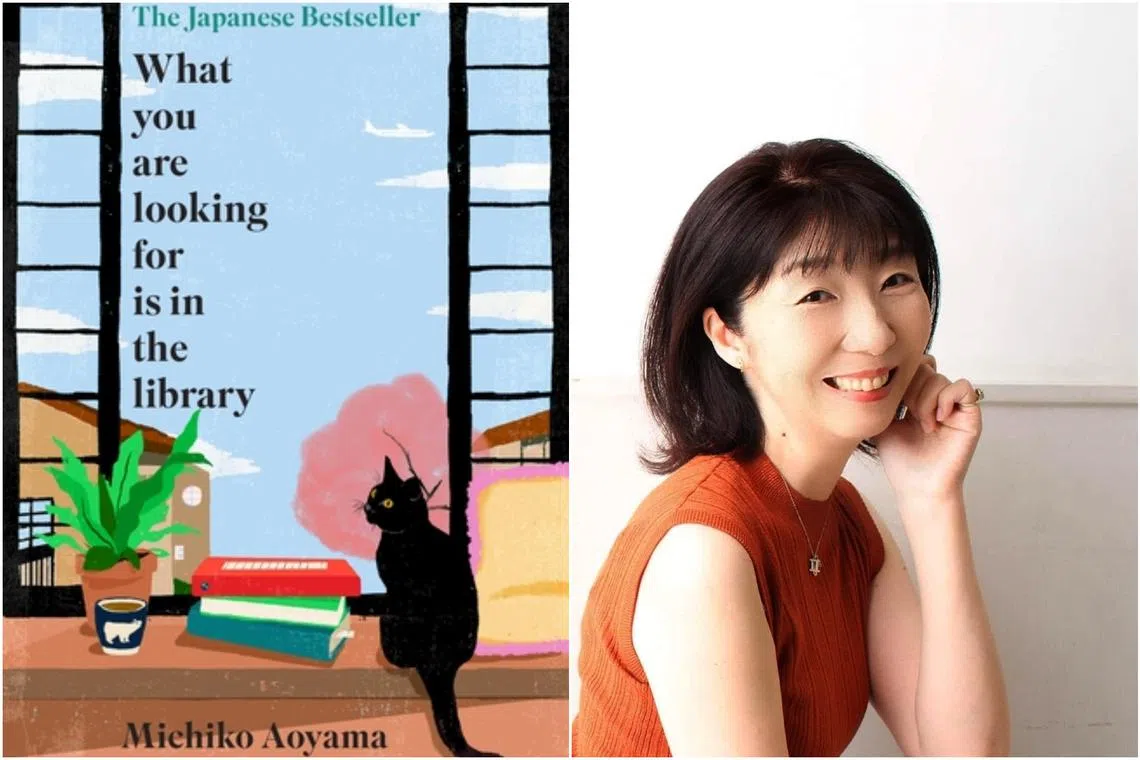

Book review: What You Are Looking For Is In The Library is a paean to the power of books

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Michiko Aoyama's down-to-earth prose is a celebration of life and all that can come with positive thinking.

PHOTO: DOUBLEDAY, MICHIKO AOYAMA

Follow topic:

What You Are Looking For Is In The Library amzn.to/40ulAAD)

By Michiko Aoyama, translated by Alison Watts

Fiction/Doubleday/Hardback/304 pages/$32.33/ Amazon SG (

3 stars

As expected from its title, What You Are Looking For Is In The Library is a paean to literature and the power of books.

Beneath the surface of Japanese writer Michiko Aoyama’s down-to-earth and almost soppily sentimental prose is a celebration of life and all that can come with positive thinking.

These themes are obviously universal and the book, first published in 2020, has not only been shortlisted for the Japan Booksellers’ Award, but has also been translated into more than 20 languages.

The five everyman protagonists, all of them connected within the tapestry of their community yet unknown to one another, have lost their way in life. They all feel isolated, either from their ideal selves or the world around them.

Tomoka, a 21-year-old retail assistant, is unmotivated by what she sees as a dead-end job. Ryo, a 35-year-old accountant, wants to chase his dreams but fears losing a stable rice bowl with marriage on the cards.

New mother Natsumi, 40, is angry at being passed over for promotion at a publishing house after maternity leave. The unemployed Hiroya, 30, is blessed with a talent for drawing but cannot find a suitable job. And the recently retired salaryman Masao, 65, feels aimless with all the free time he suddenly has on his hands.

For their own reasons, they end up at the local community library where they meet its enigmatic librarian Sayuri Komachi.

In her, Aoyama creates a caricature of an unapproachable ogre, and all five characters recoil when they meet her.

The descriptions border uncomfortably on fat-shaming, with such “a humongous, fearsome woman squished behind the counter” and “you can’t even see where her chin ends and her neck begins”.

But in the very obvious cliche not to judge a book by its cover, Komachi is kind and hypersensitive to the emotional turmoil that her clients are facing. She starts off by asking: “What are you looking for?”

She uses her seemingly preternatural powers to suggest books that are on the surface completely unrelated to what the characters were searching for. Yet, she hits the nail on the head with titles that include children’s books and poetry, through which life lessons get imparted.

“Readers make their own personal connections to words, irrespective of the writer’s intentions, and each reader gains something unique,” says Komachi, refusing to take any credit.

The novel is transcendent, almost preachy. Another character avers: “Every kind of contact between people makes them part of society. And that goes beyond the present moment. Things happen as a result of our points of connection, in the past and in the future.”

It is no spoiler that all five protagonists will find their happy ending in their respective journeys of discovery, though Aoyama regrettably does not delve into the back story of Komachi, easily the novel’s most interesting character.

By the end, even though the life lessons may seem repetitve, Aoyama succeeds in nudging readers to look within themselves in a moment of introspection.

If you like this, read: The Cat Who Saved Books: A Novel by Sosuke Natsukawa, translated by Louise Heal Kawai (HarperVia, 2021, $31.30, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/462Qpxu

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.