Book review: Tracy Chevalier’s The Glassmaker disappoints with awkward plot device

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Set mainly in Murano, The Glassmaker centres on the Rosso family, who make glassware.

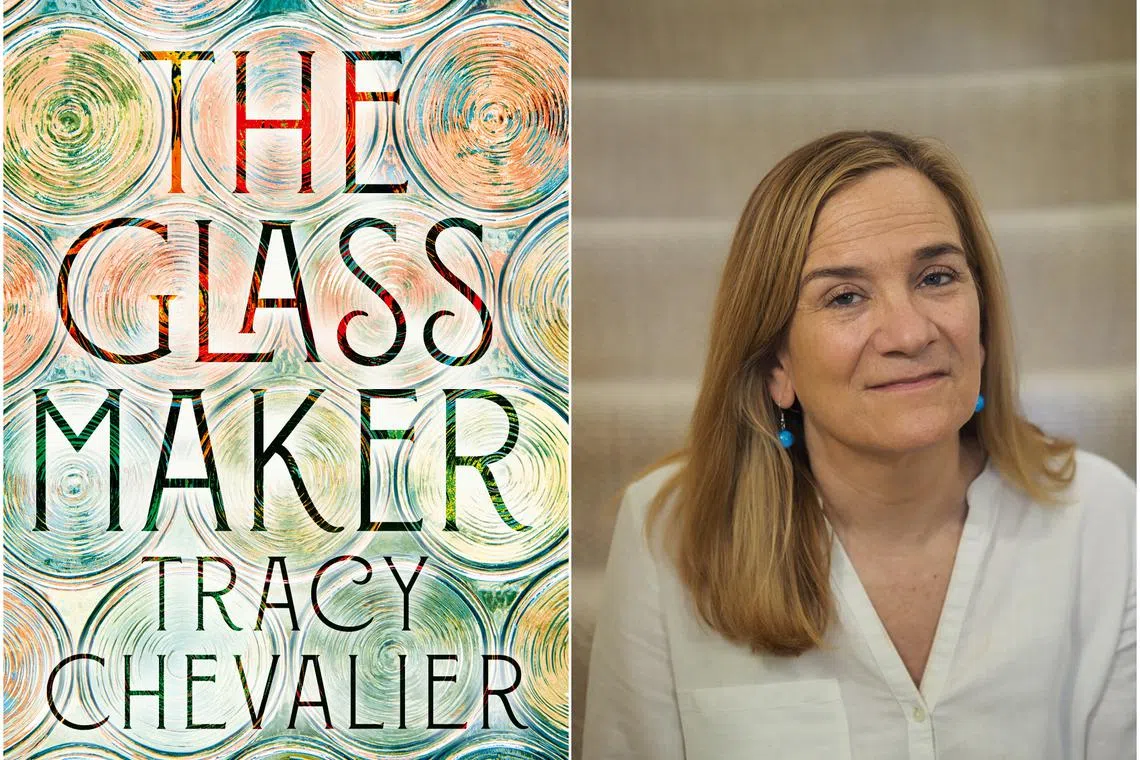

PHOTOS: THE BOROUGH PRESS, JONATHAN DRORI

Follow topic:

The Glassmaker

By Tracy Chevalier amzn.to/3XWHEEW

Fiction/The Borough Press/Paperback/400 pages/$19.45/Amazon SG (

Whether you take to Tracy Chevalier’s latest novel depends on whether you accept her central narrative conceit.

Set mainly in Murano, a more drab cousin to the glamorous city of Venice, The Glassmaker centres on the Rosso family, who make glassware. Even today, the string of seven islands connected by bridges and canals is famed for glass, an industry that took root in the 13th century after the Venetian authorities banished the makers to offshore islands.

Long-time Chevalier fans will expect another one of her meticulously researched and richly evocative depictions of historical periods. There is plenty of that in evidence, but her signature historical-fiction style, which emphasises authenticity and period detail, clashes with the aforementioned narrative conceit, which employs a different genre trope to rather negative effect.

A brief prologue explains the plot device. Drawing a parallel with the debate over whether glass is a solid or a liquid, Chevalier sets up the idea that time flows slower in the city of Venice and Murano.

So while members of the Rosso family age slowly, the centuries spin past at regular speed in the world outside. Each great leap in time is marked by an opening paragraph that likens the narrative to a flat stone skimming across a pond. So each time the stone – also known as the narrative – touches down in time, the world has skipped 80 or more years, while the Rosso family, and everyone the members know in Venice, have aged mere decades.

As an avid reader of fantasy and science fiction, this reviewer is not averse to crazy flights of fancy. But The Glassmaker’s conceit does not impact what is, essentially, a simple story. What is worse is that the constant reminder of this awkward structural device at the beginning of each section rips the reader from full immersion in Orsola’s story.

Orsola is the third child of the Rosso family, a girl who, when the story begins in 1486, is expected to help only with cooking and laundry before marrying into another family. Her elder brother Marco is the one her father Lorenzo imparts the family’s glassmaking recipes and secrets to.

Orsola’s mother Laura, however, has aspirations for the family and pushes Orsola to learn beadmaking from Maria Barovier, a rare female glassmaker from a rival family. Predictably, Orsola’s beadmaking skills become critical to the family’s survival over the years.

The craft and techniques of glassmaking are depicted with care, as is the scene-setting of the storytelling, full of the wonders of Venice at the peak of its power and glamour as the centre of world trade and barter in the 15th century, as well as its slow decline into the contemporary city better known as a tourist destination in danger of sinking into the ocean.

While Orsola rarely leaves Murano, she gets glimpses of world upheavals as her handmade beads are traded through the hands of German businessman Gottfried Klingenberg, the middleman for the Rossos’ wares. As the world turns, she, too, has to keep up with the times, going from making highly coveted luxury items to cheap seed beads that help fund the colonial exploitation of the Americas and Africa.

Other than these tiny ripples of demand on the Rossos’ wares, the strangeness of the world moving so fast outside Murano and Venice has zero effect on the Rosso family. No character in this book questions why the family members are practically immortal and placidly live out their daily routines.

This weird disjunct detracts from the central perfectly serviceable story of a woman dealing with personal desires and ambition in a patriarchal system.

The story device seeks to free the narrative from time constraints as Chevalier introduces various gimmicky cameos by historical figures, including a brief appearance by Casanova. It also allows her to work in snapshots of changing social norms and dramatic historical events, such as the 1574 plague epidemic in Venice and Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1796 invasion of Venice.

But the scale and impact of these historical events do not dent the central characters’ psychological make-up, which only results in alienating the reader from the dramatic personae. This Glassmaker is more muddy than it needs to be and is likely for only the most dedicated Chevalier fan.

Rating: 2 stars

If you like this, read: Girl With A Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier (Penguin Classics, 2000, $22.92, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/4cU7SMg

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.