Book review: Three non-fiction books on Singapore’s policy issues

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Follow topic:

Singapore Is Still Not An Island

By Bilahari Kausikan, edited by Tan Lian Choo str.sg/iTHQ

Non-fiction/Straits Times Press/Paperback/381pages/$34.68/Books Kinokuniya (

4 stars

Singapore’s Grand Strategy

By Ang Cheng Guan str.sg/iTHA

Non-fiction/NUS Press Singapore/Paperback/208 pages/$32/NUS Press (

3 stars

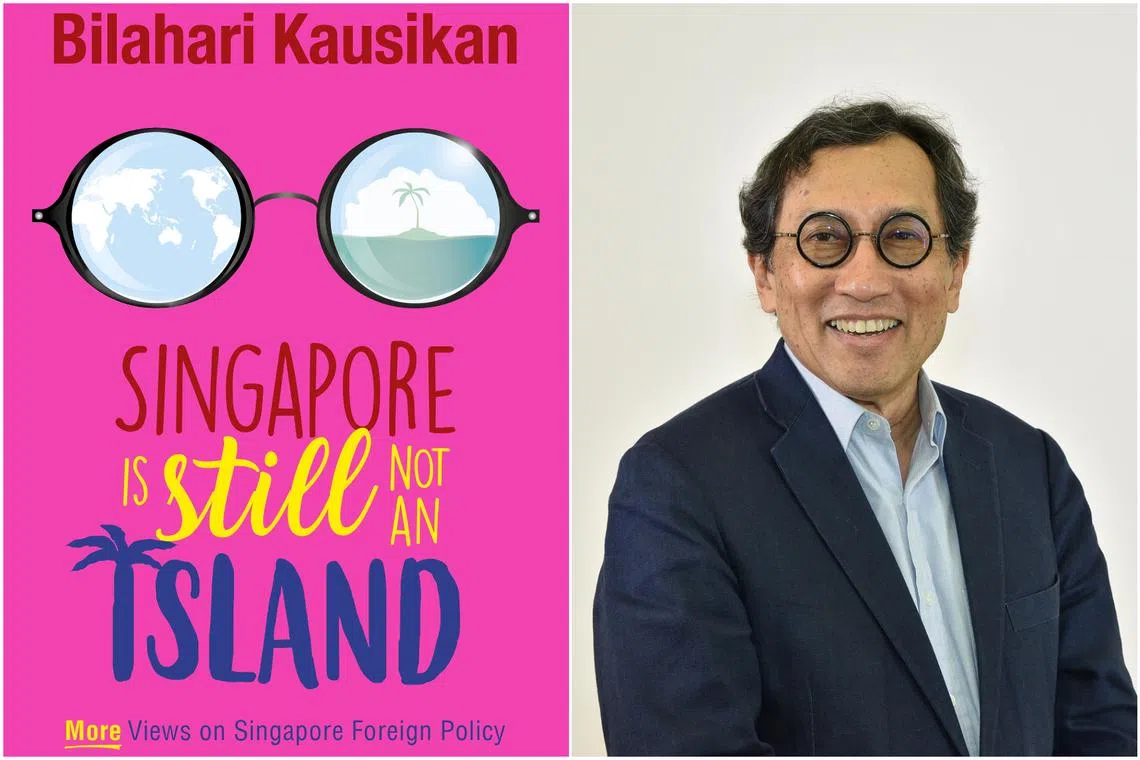

The Singapore I Recognise: Essays On Home, Community And Hope

By Kirsten Han str.sg/iTHd

Non-fiction/Ethos Books/Paperback/264 pages/$26/Ethos Books (

4 stars

Bilahari Kausikan is the author of Singapore Is Still Not An Island.

PHOTOS: ST PRESS

Last weekend, on the occasion of United States President Joe Biden’s visit to Hanoi, highest of its three diplomatic levels.

This put the US in the same category as China and Russia (as well as India and South Korea) with regard to the ruling communist party of Vietnam, and incidentally proved former Singapore diplomat Bilahari Kausikan right.

One of the many insights he allows readers in his new book, Singapore Is Still Not An Island, is that the rest of South-east Asia is finally catching up to what the Republic has consistently advocated for decades. In the face of a more aggressive China, more actively engaging the US in the region will give states here more, not less, manoeuvrability.

This book is the sequel to Kausikan’s Singapore Is Not An Island (2017), also edited by Tan Lian Choo, former press secretary to the Foreign Minister.

Kausikan was Singapore ambassador to the Russian Federation, permanent representative to the United Nations and permanent secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, among other posts he held in his 37 years in diplomacy.

His thoughts are once more pulled together from his lectures, speeches and articles, this time focusing on Singapore and Asean in the face of increasing US-China tensions.

He highlights the problems of superficial applications of Cold War rhetoric to US-China relations, noting that the two are enmeshed in a global economic system in a way the US and the Soviet Union never were.

More importantly, he argues against those convinced of China’s inexorable rise and the US’ seemingly obvious decline.

China’s economic growth has hit a structurally induced plateau and its foreign policy demands are increasingly being resisted everywhere, he says.

The US’ apparent withdrawal unto itself is also more a correction of the historically aberrant period of American unipolarism post-Cold War.

Without the Soviet Union as an existential threat, it is only natural that it can now afford to be more transactional and get its allies to step up to the plate in maintaining global order.

Kausikan believes these are important modifiers to how Singaporeans should think about the US and China, because domestic and foreign policy will intersect more and more as louder calls are made for Singapore to side with either in the polarised environment.

A population not so easily taken in by historical teleologies and distracting sleights of hand will be able to make clearer assessments of how to preserve Singapore’s core interests, which for him are the essential values of “multicultural meritocracy”, particularly at risk with China’s appeals to Han-ethnic solidarity.

The format of the book perhaps makes for repetitive reading, with Kausikan not averse to self-plagiarise in different contexts, but the overall effect is one of a crystal-clear mind able to discern long-term trends without being beholden to ideology.

Kausikan’s retiree status allows him to speak frankly on issues such as why Singapore may have compromised on its principle of sovereignty during its support for the Gulf War after the 9/11 terrorist attacks; or why instead of denuclearisation, the long-term balance for the region might lie in a multipolar nuclear regional equation that includes nuclear deterrence for Japan and the two Koreas.

Ang Cheng Guan is the author of Singapore's Grand Strategy.

PHOTOS: NUS PRESS

Another newly published, perhaps more conventional, book on Singapore’s foreign policy is Nanyang Technological University professor Ang Cheng Guan’s Singapore’s Grand Strategy.

The professor of the international history of South-east Asia applies the concept usually used for the US to a small state like Singapore to make the point that small states can have long-term strategies, too, and are not just price-takers.

The grand strategy idea is exactly as it sounds – a country’s complex form of planning towards the fulfilment of a long-term objective.

By studying the speeches made by Singapore politicians – and sometimes filling them in with archives from other countries – Ang argues that Singapore’s approach has been remarkably consistent since its independence in 1965.

The 4G leadership continues to “sing from the same songsheet” composed by first-generation leaders Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam, he argues, carefully managing relations with Malaysia, Indonesia, US and China while supporting multilateralism, rule of law and a strong Singapore Armed Forces.

While his conclusions should not be surprising to any Singaporean, its value lies in expanding the range of international grand strategy case studies in academia and policy studies to include smaller states.

Kirsten Han is the author of The Singapore I Recognise.

PHOTOS: ETHOS BOOKS, GRACE BAEY

Kirsten Han’s The Singapore I Recognise is a collection of essays by the long-time civil society activist, expressing trenchantly her thoughts on the difficulty of dissent and the overwhelming power of the state in Singapore.

The writings are wide-ranging, effectively going over how this power imbalance manifests in different aspects of Singaporean life – from how Singapore’s education system discourages systemic critique to the problems with some civil society groups choosing to cooperate with the establishment to advance their cause.

Han, who says her learning about the 1987 Operation Spectrum was “the first crack that would widen my field of vision in time to come”, also talks about the need for Singaporeans to reconnect with its history of dissent.

She herself attends an annual lunch gathering with the Old Left and talks about the lingering trauma government crackdowns in the 20th century has had on civil society.

Operation Spectrum saw the arrest of 22 people under the Internal Security Act, including church volunteer Vincent Cheng, who still avoids eating ang ku kueh because it was what he was fed after his allegedly coerced confession.

Many of Han’s topics of discussion are recent developments and should make for timely reading, including the passing of the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (Pofma) and Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act (Fica).

There are also behind-the-scenes descriptions of her experiences with police investigations – her fitness tracker showed she had completed more than 400 minutes of exercise based on her heart rate after one such ordeal – and online bullying, after she was accused of being a traitor for meeting then-Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in 2018, together with historian Thum Ping Tjin, graphic novelist Sonny Liew, political dissident Tan Wah Piow and activist Jolovan Wham.

The title itself is a rejoinder to a letter written by Singapore’s ambassador to the US Ashok Kumar Mirpuri in 2018, who said that “I cannot recognise the country Ms Han describes”, in retort to an article by Han which painted Singapore as an authoritarian paradise.

This book is a love letter to not just Singapore’s civil society, but also Singapore as a whole, though the right to criticise should not be based on proof of love, Han notes.

“Dissent isn’t betrayal. It’s a necessary feature for democracy to work.”

In an unforgiving system, it also holds a call for empathy.

“Instead of allowing fear and mutual policing to drive wedges between us, we can train ourselves not to leap to judge other people’s choices, strategies and methods, but prioritise public and private demonstrations of solidarity.”

Correction note: This article has been updated to correct Mr Bilahari Kausikan’s designation. We are sorry for the error.