Book review: The Devil’s Playground dives into 1920s Hollywood and the occult

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

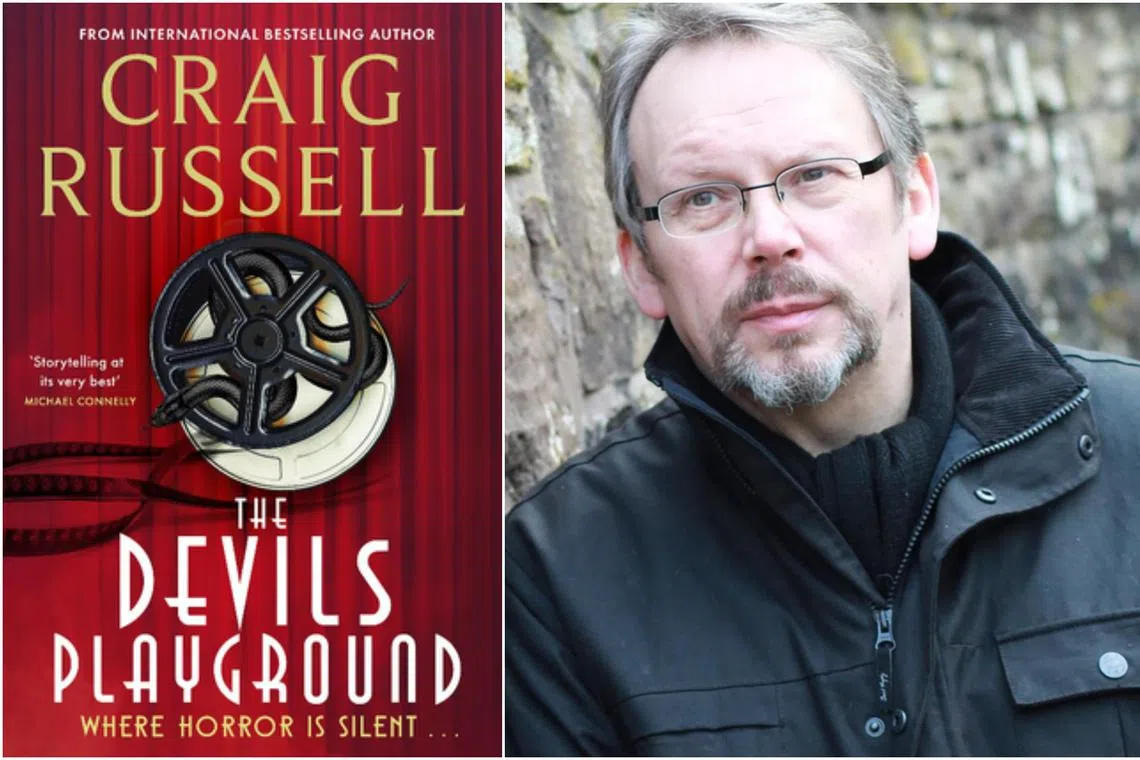

The Devil’s Playground By Craig Russell.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF DOUBLEDAY, COURTESY OF JACK RUSSELL

The Devil’s Playground By Craig Russell

Horror/Doubleday/Hardcover/464 pages/$38.47/Amazon SG ( amzn.to/3OjrNcQ

4 stars

The Devil’s Playground was said to be the greatest silent horror film, shrouded in rumours of a curse that led to its destruction before anyone could watch it.

When its lead actress Norma Carlton dies of an apparent suicide, studio fixer Mary Rourke covers it up before realising she unwittingly becomes an accessory to murder.

Tasked to find the truth behind Norma’s death, Mary uncovers strange connections to the occult and worse secrets than what she has helped hide.

Early on, Mary describes her job: “(She) has always maintained a cynical detachment in her job, but when she had to use threats and payoffs to keep one of (Carbine film studio’s deputy Clifford J.) Taylor’s worst incidents out of the papers – and potentially the courts – she had seriously considered changing to a more edifying career, like cleaning sewers.”

Taking place primarily in 1927, Scottish author Craig Russell’s story explores the nitty-gritty world of Hollywood two years before sound revolutionised film-making, with The Devil’s Playground as the gateway to understanding how an unreleased film can become a legend.

Meanwhile, in 1967, film historian Paul Conway tracks down a rumoured final copy of The Devil’s Playground. The only thing left is to see how horrifying it truly was.

Where the novel shines is Russell’s fascinating depiction of 1920s Hollywood through Mary’s job, particularly as she becomes increasingly disgusted by the reality of the secrets she has helped conceal.

Her skills as a fixer translate to her search for the truth, though she sometimes fails to connect obvious clues.

A bonus is the clear homage to the skill required of film-making in the 1920s.

While watching The Devil’s Playground, Conway “marvels at the artistry of the mise-en-scene: the architecture of the cathedral is impossible yet credible; the clutching huddle of the city’s buildings seems the fanciful conjuring of an artist’s imagination, yet (he) can believe these people really live there”.

Clocking in at 464 pages, the novel drags towards the end, providing ending after ending that leaves this reviewer wondering what the intended impact is.

Most of the conclusions are wrapped up in an info-dump across the four final chapters and an epilogue, telling rather than showing where the final pieces fit into place.

Lingering questions remain as character actions in the final 1927 and 1967 chapters are largely unexplained. A grand twist set in motion during 1927 falls flat during its 1967 reveal.

The result is a tonally confusing end to what is otherwise an exciting and intriguing mystery.

If you like this, read: Night Film by Marisha Pessl (Penguin Random House, 2014, $15.25, Amazon, go to amzn.to/3YdfHGR

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.