Book review: Taste the sea in Lala-land: Singapore’s Seafood Heritage

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

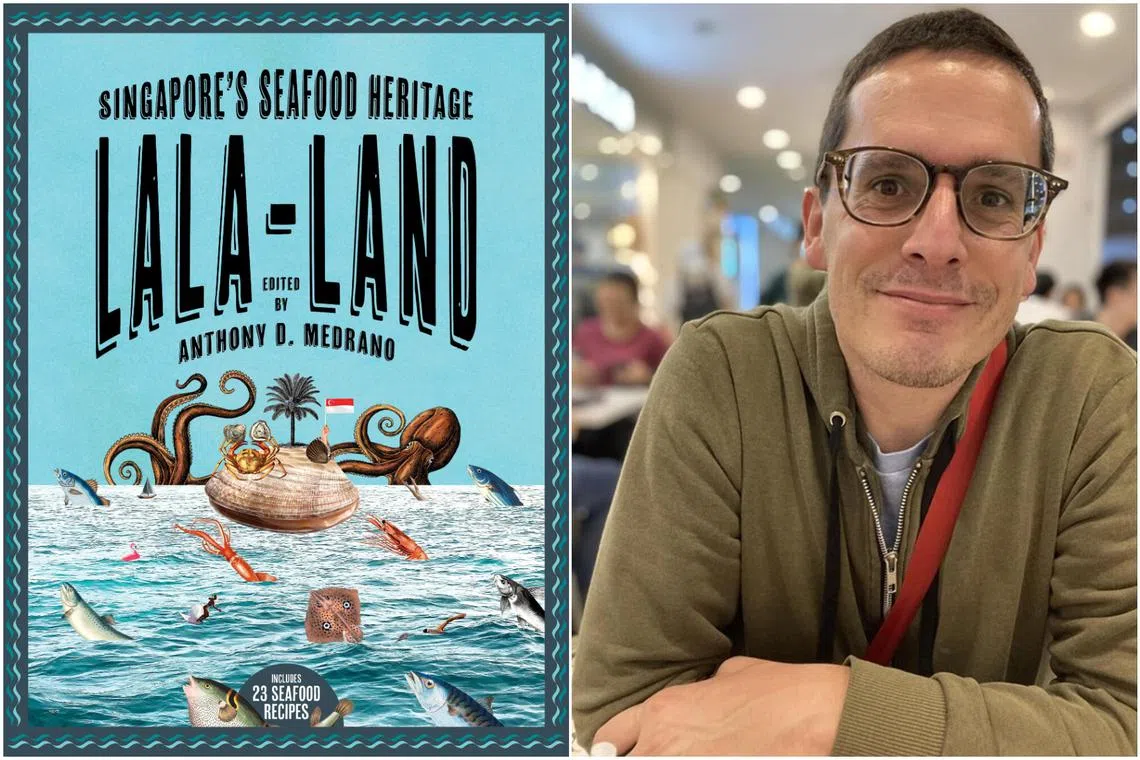

Lala-land: Singapore’s Seafood Heritage, edited by Anthony D. Medrano, weaves together myriad voices for an insightful read on Singapore's food.

PHOTO: EPIGRAM BOOKSHOP, YALE-NUS COLLEGE

Follow topic:

Lala-land: Singapore’s Seafood Heritage

Edited by Anthony D. Medrano amzn.to/4bIYGJW

Non-fiction/Epigram Books/Hardcover/300 pages/$36.72/Amazon SG (

Singaporeans like to brag that they know their food and, yet, how many have tried the elusive Siglap laksa – precursor to the iconic Katong variant – or stir-fried ikan buntal, or pufferfish?

Though this delectable but deadly fish has become synonymous with Japanese fine dining, it can be found right here, swimming along the shores of Singapore. And one community, the Orang Laut, has caught and cooked it successfully for centuries.

Such hidden stories wash up on the pages of Lala-land: Singapore’s Seafood Heritage, a collection of essays edited by Anthony D. Medrano, the NUS Presidential Young Professor of Environmental Studies at Yale-NUS College.

Part ecological textbook, part historical survey and part recipe book, it weaves together myriad voices, from undergraduates’ to seasoned writers’. Their meticulously researched essays aim to chart the journey from ocean to table, and prove an insightful read for anyone whose interest in seafood goes beyond just its taste.

Contributors have cast their net into the sea of information and hauled up a bounty. Paragraphs delve into the etymology of fish names, how species such as barramundi and catfish are caught or reared, and how hawker favourites like sambal stingray attained their national dish status.

Occasionally, the essays touch on wider issues too. Questions of animal cruelty surface in a thoughtful piece about drunken prawns, while another chapter on prawns comprehensively unpicks concerns about sustainability and human rights so often entangled in the mangroves where these crustaceans are farmed.

Later chapters also make brief mention of Singapore’s 30 by 30 plan – to grow 30 per cent of Singapore’s food needs locally and sustainably by 2030 – and the concomitant problem of food security, forcing readers to confront the murky future facing their favourite seafood dishes.

The writing is straightforward and clear, if sometimes slightly dull. It is enlivened by occasional flourishes – things take a more atmospheric turn in the chapter on Pacific oysters, for instance – and personal anecdotes.

Some parts could have done with sharper editing. You are not likely to forget that fish maw is discarded as waste in most parts of the world – that fact is mentioned twice in the opening paragraph of that chapter alone.

While I get the idea behind how the book was organised – divided between ocean (individual species of seafood) and table (dishes like char kway teow and sambal goreng) – later chapters discussing ingredients already covered in previous essays sound rather repetitive.

Prawn aquaculture, for example, is mentioned in four separate chapters. Two writers talk about otak otak. Another two contribute oyster omelette recipes, albeit in different styles, and trace the arrival of this dish to Singapore.

Apart from that one overlap, the book serves up a mix of recipes suitable for cooks of varying skill levels. I start simple, first attempting the four-step tuna mayonnaise pasta salad recipe – one of the few dishes in the book without local or regional origins.

The tuna mayonnaise pasta salad this reviewer made following the recipe in Lala-Land.

ST PHOTO: CHERIE LOK

As expected, it turns out to be a mostly painless process. I manage to put together a decent meal in under 20 minutes, and clear out my leftover bell peppers in the process.

Emboldened by my small success, I take a stab at two more complex recipes: Hokkien mee – fried, as suggested, without pork lard, which it sorely misses – and salmon urap with raw vegetables – a dish so fiery, it nearly burns down my kitchen, though mainly due to a mistake I made while deep-frying the fish skin (and the fact that I may have overestimated my spice tolerance by adding the prescribed amount of chilli).

This reviewer also attempted the book’s salmon urap with raw vegetables.

ST PHOTO: CHERIE LOK

The book does not state how long you will need for each recipe, so I budget an hour a dish and end up overshooting both times by about 15 minutes.

Still, I had fun challenging myself and diving into the rich marine ecosystem that feeds food-loving Singapore.

Rating: 4 stars

If you like this, read: Tok Panjang by Arthur S.K. Lim (Landmark Books, 2023, $27.50, go to str.sg/krXq), in which the author traces the history of Tok Panjang, known today as a lavish Peranakan banquet, and shares his Nonya mother’s time-tested recipes along the way.

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.