Book review: Tale of North Korean trickster survivor overreaches, but still enthralls

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

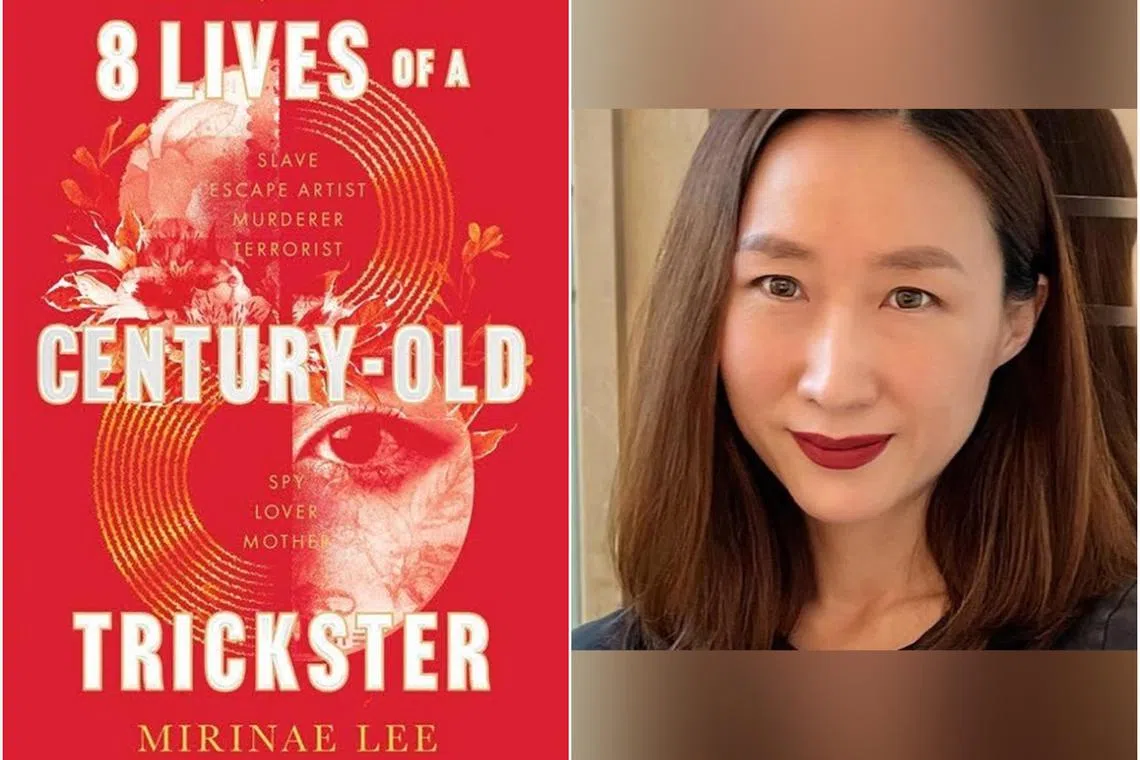

Mirinae Lee’s debut novel 8 Lives Of A Century-Old Trickster thrills with adventures inspired by her great-aunt’s escape from North Korea.

PHOTOS: VICTOIRE LETHIELLEUX

8 Lives Of A Century-Old Trickster

By Mirinae Lee

Fiction/Virago/Softcover/304 pages/$33.29/Books Kinokuniya

4 stars

A middle-aged personal assistant going through a divorce decides to write one-page obituaries for elderly residents in the nursing home where she works. Meanwhile, an old woman, who survived the Korean War and World War II, becomes a resident at the home.

At its best, Mirinae Lee’s debut novel 8 Lives Of A Century-Old Trickster thrills with adventures inspired by her great-aunt’s escape from North Korea.

Readers cheer for the underdog, and there are few more delightful than gifted trickster Mook Miran, who grows from victim to bad-a** as she reclaims her life and takes those of her abusers.

The revenge she exacts is sweet and the redemption she finds provides relief from the harrowing accounts of rape and abuse.

The violence of Japanese soldiers against comfort women, narrated in a matter-of-fact tone, is often uncomfortable and hard to read.

The prose struggles to live up to the ambitious subject matter and is slightly awkward in parts.

The narrative structure cobbles together nine chapters, five of which have been published in American literary journals as short stories.

Still, Lee grabs attention with the book’s rich historical detail, taking the reader to North Korea under the regime of Kim Il Sung – citizens’ surveillance of one another, public executions for minor infractions like watching American pornography and an exercise where schoolchildren confess their sins against the Communist Party.

The second half makes for a gripping read. Mook falls in love and starts a family, and the stakes of deception multiply.

Lee’s characterisation here becomes far more compelling. The mother-child and husband-wife relationships, which start out duplicitous, are sensitively painted in all their complexity.

Perhaps these are experiences Lee is more familiar with, as she is married with children.

In one wrenching passage, Mook’s daughter Mihee, whose premature newborn is in the neonatal intensive care unit, learns that she can pray.

“Or do You want me to come clean?” she asks, quickly adding that she can “turn myself in tomorrow first thing in the morning, if You guarantee he’ll live, just healthy and normal”.

She later realises that this desperate negotiation with invisible forces is her first prayer.

After Mook finishes telling her story, the narrative is undercut by the obituarist, who questions its veracity. How can one person possibly live all these lives?

An early allusion to the role of storytelling in soothing the brutalised comfort women offers a hint: “The reality wasn’t as beautiful as the stories we told each other in secret at night.”

Perhaps Mook herself is using storytelling as a balm, decades after suffering horrific abuse. But the pieces Lee offers fall neatly into place at the end, leaving little room for imagination.

The happy ending for Mook’s story, however, rings a little false. It could have been read more interestingly and convincingly as an unreliable narrator’s attempt to write herself a happy ending.

In a more generous reading, this is just a measure of how good a liar the trickster is.

If you like this, read: Pachinko by Min Jin Lee (Apollo, 2017, $20.13, Books Kinokuniya), which follows a Korean family of immigrants through eight decades and four generations.

This article includes affiliate links. When you buy through them, we may earn a small commission.