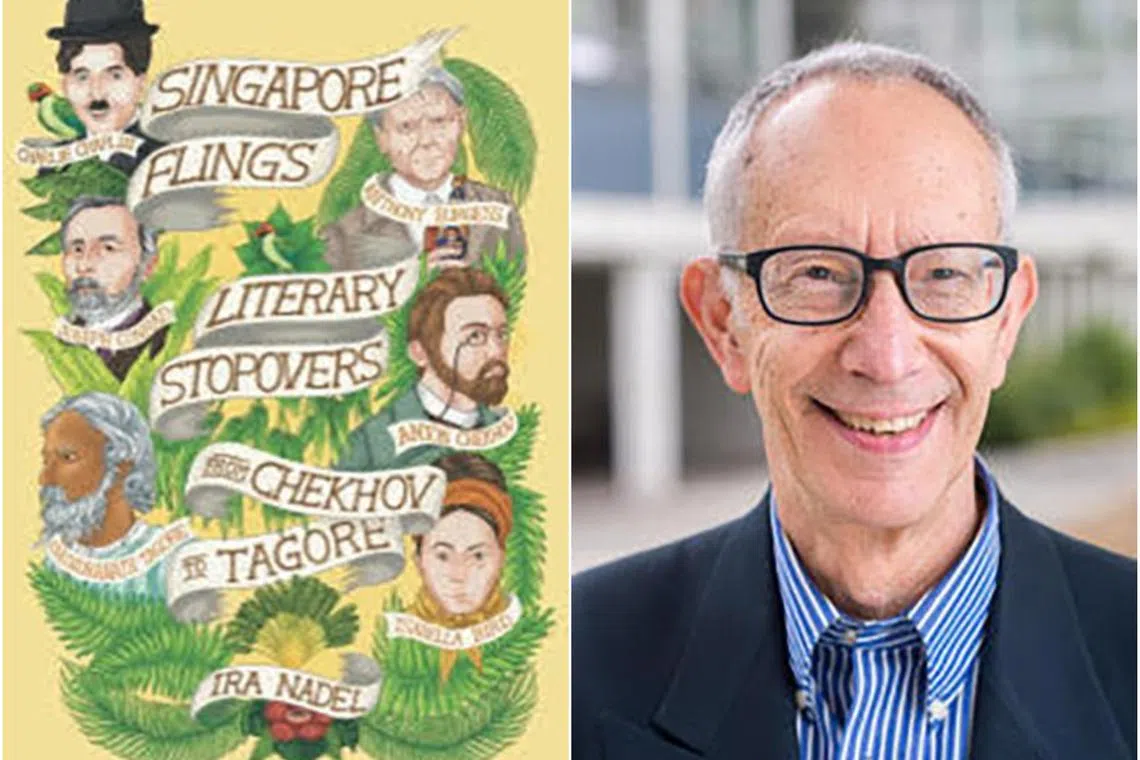

Book review: Singapore Flings traces the little-known connections famous writers have with Singapore

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Canadian biographer Ira Nadel collected the interactions of 21 literary writers with Singapore in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

PHOTOS: EPIGRAM BOOKS

Singapore Flings: Literary Stopovers From Chekhov To Tagore

By Ira Nadel amzn.to/3r7D7Rm

Non-fiction/Epigram Books/Paperback/275 pages/$29.05/Amazon Books (

4 stars

Social theorist Walter Benjamin famously urged historians to write “against the grain”.

By analysing the writings of white authors not as objective fact but a point of view, the colonised can more easily critique Anglo-European ideas of the non-Western world – parsing their contradictions and revealing their biases as constructs to be questioned and ultimately rejected.

That is the impulse of this anthology put together by Canadian biographer Ira Nadel, who has collected 21 literary writers’ interactions with Singapore in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

From Russian playwright Anton Chekhov to notorious imperial apologist Rudyard Kipling to Indian Nobel Prize winner and pan-Asianist Rabindranath Tagore, their travels to Singapore and the island’s impact on their writing are succinctly captured in 21 footnoted chapters, each just a few pages long.

The book makes for a useful reference text that doubles as an interesting reminder of Singapore’s erstwhile allure as part of the “fabulous Orient”, where Pierre Boulle, author of The Bridge Over The River Kwai (1952), trained to be a spy; and where French film-maker and poet Jean Cocteau revelled in the opium joints and wrote, observing a ferocious captive tiger at an animal market, that there are “vast reserves of energy” with which “the Orient can challenge an exhausted Europe”.

There are surprising entries, including Chekhov’s and British absurdist Tom Stoppard’s more incidental encounters with Singapore, with Nadel admitting that any link between Singapore and their writings is marginal and speculative.

Still, it is interesting to remember that Stoppard spent his younger years here as a Czech-Jewish refugee with his family before World War II – an experience that possibly entrenched a feeling of disorientation in his plays.

For Chekhov, it was not the island itself, but the journey here.

A typhoon nearly sank his boat while he was on his way from Hong Kong, and his captain’s warning that he should shoot himself before they go under – because the waters were shark-infested – made its way into the tragic conclusion of his short story Gusev (1890).

Better documented and more concrete is the mutual love between Charlie Chaplin and Singapore. Though not a literary writer, the English comic actor visited Singapore four times between 1932 and 1961.

Singapore, as well as Bali and Japan, was a rich source of artistic inspiration for Chaplin, who borrowed from the abstract, distilled movements and improvisation of Asian theatre.

Like Cocteau, he found the “emblematic acting” at New World Amusement Park fascinating, incorporating it in his mimes in his silent comedies like Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940).

One of the most complex chapters is on Anthony Burgess, the English author of A Clockwork Orange (1962), who might have been a failed writer if not for his Malayan trilogy, written in what was then Malaya.

Beginning with Time For A Tiger (1956) – a reference not to the beasts stalking the jungles but to Tiger Beer – he would grow from a man looking to drink tropical gin to one with real love for the inhabitants here, learning the language and centring native characters in a way antithetical to English writer William Somerset Maugham’s obsession with the colonial class.

It is heartening to read about Burgess’ admiration for local writers Lee Tzu Pheng, Edwin Thumboo, Chandra Nair, Arthur Yap and Robert Yeo in his autobiography – a world of difference from Kipling’s retrospectively comical thought-gymnastics, in which he goes from lamenting English laziness to conclude: “It is a glorious thing to be an Englishman.”

A slightly incoherent introduction mars this research, but there are literary flings to be had for any reader willing to flit in and out.

The port city of Singapore may have mostly been a point of transit for the majority of these literary giants, but it was far from sterile. Nadel’s book proves it has made its own niche contributions to canonical literature.

If you like this, read: Travellers’ Tales Of Old Singapore: Expanded Bicentennial Edition by Michael Wise (Epigram Books, 2018, $29.96, Amazon, go to amzn.to/3PtXGSb

This article includes affiliate links. When you buy through them, we may earn a small commission.