Book review: Self-Portraits by Osamu Dazai rare translation of a cult Japanese author

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Self-Portraits by Osamu Dazai is translated by Ralph McCarthy.

PHOTO: NEW DIRECTIONS, NEW DIRECTIONS

Self-Portraits

By Osamu Dazai, translated by Ralph McCarthy amzn.to/3UFkWhf

Fiction/New Directions/Paperback/232 pages/$24.16/Amazon SG (

4 stars

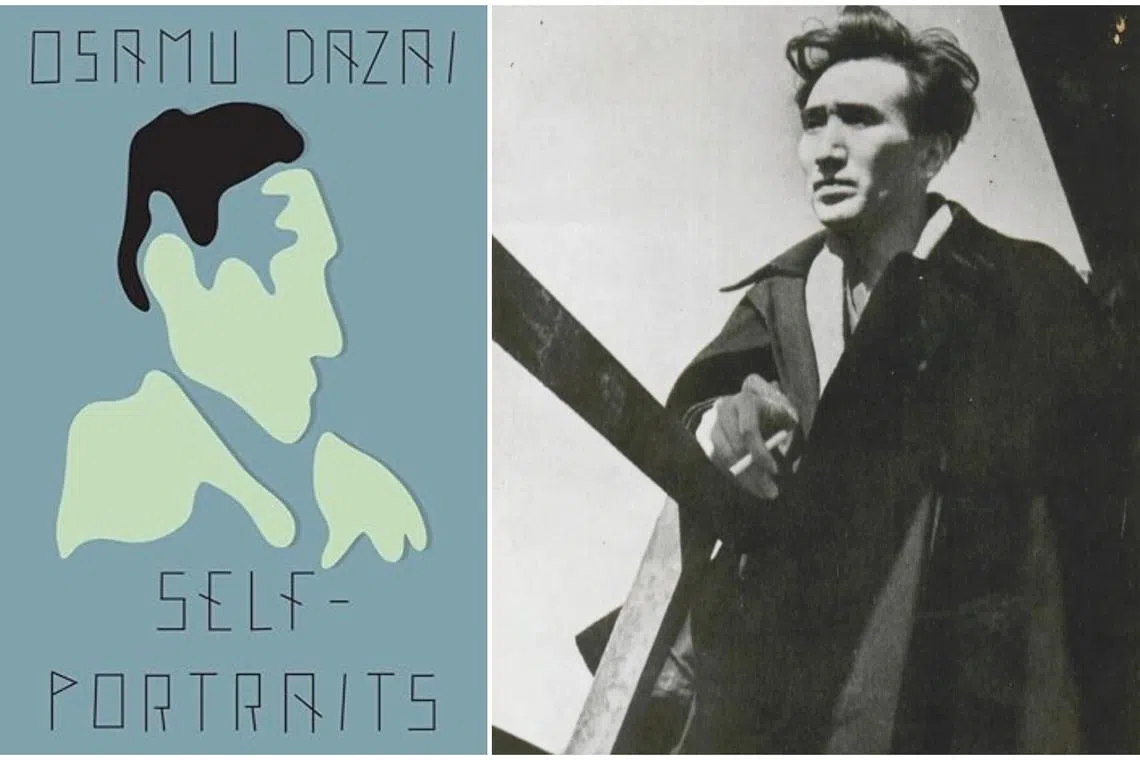

Born in 1909 in Aomori prefecture, the scandalous writer Osamu Dazai, though little known in the Anglophone world, still has a cult-like following in Japan.

In life, the decadent romantic was shunned by the Japanese literary community for his drunkenness, addiction to painkillers and generally antisocial behaviour.

But chief of the controversies surrounding him is his notorious record of multiple suicide attempts, usually with a young woman in tow.

He survived his first double suicide attempt at age 20, but his companion died – a cause celebre that was his unfortunate first claim to fame.

It was also via a double suicide – this time by drowning rather than sleeping pills – that he finally ended his life in 1948, having struggled his entire life with reconciling a desire to be accepted and his inability to play by the rules.

Self-Portraits, translated by Ralph McCartney, is a collection of some of Dazai’s short stories, all liberally drawing from details of his life and wearing his tortured heart on his sleeve.

McCartney’s interest is as much with Dazai’s scarcely believable biography as his writing.

The stories selected are nearly all without fictional edifice. His editorial introduction of Dazai serves as a map for English readers to navigate Dazai’s tumultuous life and locate the stories’ genesis.

Dazai is not so much refracted in his stories as completely visible in them. His writing, as he confesses, is motivated by “a burning obsession” to purge and cleanse, containing an ardent, autofictional bent.

“I couldn’t die yet. I now wanted to set it all down, to make a clean breast of my entire life until then, to confess everything,” he writes.

Of the original sin of his first suicide attempt, he laments that “I’ve written any number of times about the person who died. It’s a black spot on my entire life”.

Other turning points make for whole short stories.

The premature death of a beloved younger brother in My Elder Brothers; effectively robbing a stranger – masquerading as a joke played on an unsuspecting new entrant to Tokyo – in No Kidding; and fleeing from the Allied bombardment during World War II with his daughter suffering stoically from severe conjunctivitis throughout the ordeal in Early Light.

Though these are the scribblings of a deviant, Dazai’s love for the world and life is a constant, notwithstanding his cynical exterior.

It is the most idealistic who are often the harshest critics, and nowhere is this more evident than in One Hundred Views Of Mount Fuji, one of the longer stories in the book at 28 pages.

Written during an extended stay in Misaka Pass, 1,300m above sea level, he begins with shaming Mount Fuji for its squatness, not living up to the expectations set up by artists Hiroshige and Hokusai.

Yet, later, when its peak is obscured by clouds, he underestimates its height and finds hope in this surprise, before promptly reverting to depression one drunken night when he hears a cyclist shout about Mount Fuji and the cold.

This slippage in attitudes towards Fuji would continue throughout his stay there, the popular mountain a stand-in for his sentiment towards the people around him and mainstream society.

He finds the straightforward beauty of Fuji “crass and embarrassing”, but at other times, concedes it is impressive and is not averse to sending up a clandestine prayer.

Its “elemental expression” contains a quality he aspires to in his writing, but there was also something in its “exceedingly conical simplicity” that was too much for him.

“Trying to come to terms with the Great View of Fuji all but did me in,” Dazai writes, exasperated.

This reflexivity and sensitivity to any deviation from perfection unlocks sympathy for Dazai’s ensuing pain and dissatisfaction with life. He is unable to bond with his peers (“What a pathetic destiny, I thought – unable even to enter a barbershop without putting on airs.”) yet frequently craves intimacy and understanding, a desire that mostly manifested in womanising.

It reminded this reviewer of a line by Singapore artist Lee Wen: “Dear Life/I want to live/Dear Death/I’m ready to die.”

For Dazai, “A man has no choice but to fight. And he must win.”

This is for his fellow sufferers.

If you like this, read: What The Water Gave Me by Pascale Petit (Seren Books, 2010, $20.72, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/44LwWSJ

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.