Book review: Rachel Heng’s The Great Reclamation a sweeping epic about Singapore’s nation-building

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Rachel Heng’s The Great Reclamation takes readers back to a point in Singapore’s history when a compromise was made.

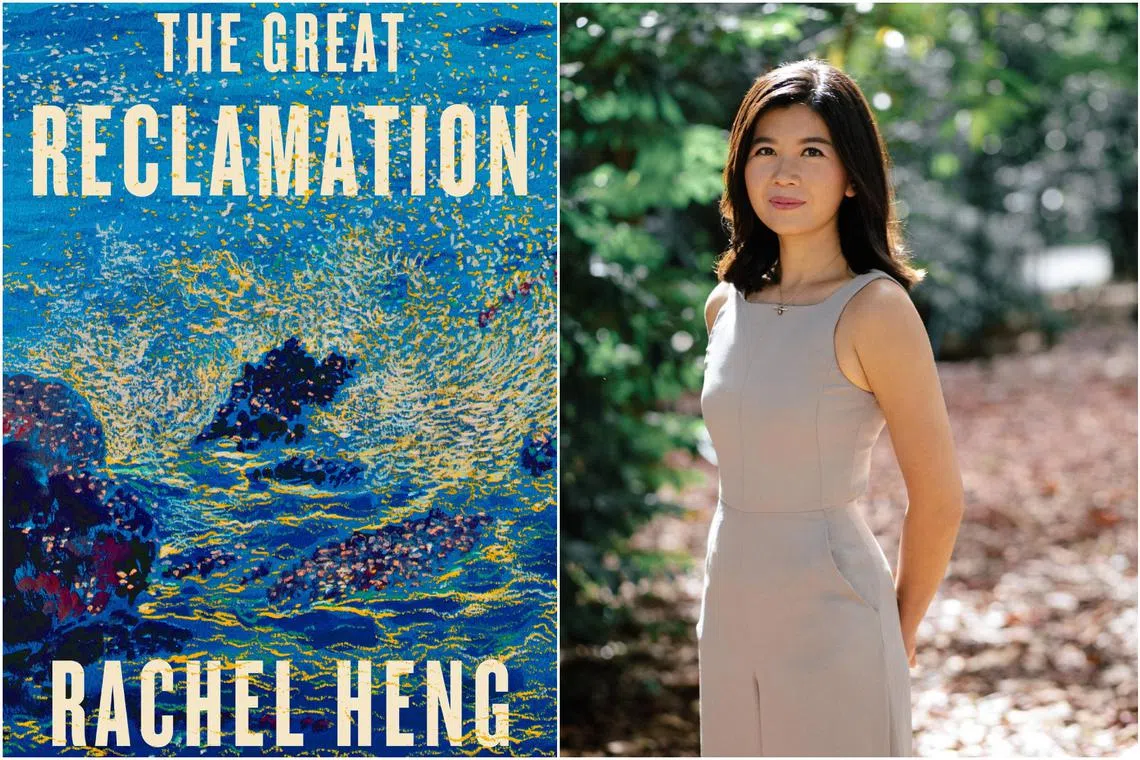

PHOTOS: JULIANA TAN, PANSING

Follow topic:

The Great Reclamation

By Rachel Heng

Fiction/Riverhead/Paperback/451 pages/$28.03/Major bookstores

5 out of 5

Rachel Heng’s The Great Reclamation is many things. It is an epic of nation-building. It is a historical fantasy. It might be the next great Singapore novel. It is almost certainly the most gripping tale of land reclamation you will read.

This is Heng’s follow-up to her 2018 debut Suicide Club, a more straightforward science-fiction thriller about longevity and mortality. Her evocative, staggeringly researched sophomore effort spans from 1941 to 1963.

It begins, as the national narrative of Singapore has done for the longest time, in a sleepy fishing village, as seven-year-old kampung boy Lee Ah Boon goes out to sea for the first time in his father’s boat.

The Lees are among the kampung’s poorest families, struggling to afford the medical bills for Ah Boon’s sickly uncle, able to send only one of two sons to school.

All this changes on that fateful fishing trip, when Ah Boon, his father and elder brother chance upon a mysterious island that has risen suddenly out of the sea. Their catch that day is unusually splendid.

The islands appear and disappear without warning, seeming to exist outside of space and time. At first, Ah Boon is the only one with the ability to locate them. He later shares the secret with the rest of the kampung, including his classmate Siok Mei, whose parents left her to join China’s war effort against the Japanese.

Ah Boon falls in love with Siok Mei, but they are drawn apart by the grand sweep of history, from the Japanese Occupation of World War II to the riots and political tumult of the 1950s and 1960s before independence.

Siok Mei becomes involved with the leftist cause, while Ah Boon throws his lot in with the nascent ruling party as they embark on the ambitious project of modernising the country.

Heng is writing primarily in the historical realist mode that characterises classic Singapore fiction by the likes of Suchen Christine Lim and Meira Chand, and more recently, Jeremy Tiang’s award-winning novel State Of Emergency (2017).

There is, however, a subtle undercurrent of the fantastic to The Great Reclamation in the form of the islands, which seem to respond to the trauma of historical events.

During the Japanese Occupation, strange catch shows up in the nets: three-tailed prawns, catfish with no eyes. As Singapore modernises, the catch in the islands’ waters dwindles.

Sand inexplicably follows Ah Boon around as he tries to persuade the kampung to leave behind the advancing coastline and move into newly built Housing Board flats.

The noise of piling from the reclamation works causes clocks to slow, shadows to pool unnaturally, and food to rot quicker than it should.

Heng’s management of these two modes is masterful. The magic is imbricated in the dominant strain of historical social realism. Yet, it casts a sheen of unreality over the story that underscores how much of Singapore’s national narrative is calculated construction.

Ah Boon is unable to shake the feeling that the country he inhabits is “a flimsy mirage, an uneasy dream of its former self”.

An architect tells him unironically at a preview of the HDB flats that will make kampungs obsolete: “It is that ineffable kampung spirit that we want to preserve.”

This is a tale of Singapore’s history, but told aslant. The various forces that rule it are referred to only by local slang terms: the Ang Mohs, the Jipunlang and, finally, the Gah Men (and, in the case of Natalie – the civil servant who is first Ah Boon’s boss and, later, love interest – the Gah Women).

This could appear glib in the hands of a less able author, but Heng grounds the story in Singapore’s landscape with a rich sense of place. She writes of its coastlines, mangroves and waters with a lucid beauty shot through with melancholy.

She depicts the act of land reclamation as “obscene”. A pit of exposed earth glistens “like gallstones in the sharp glare of a surgeon’s lamp”.

The novel does not villainise the project of nation-building outright. There is nuance and reason in her portraits of the Gah Men and their goals of progress, particularly Natalie, who is sincerely devoted to improving the lives of lower-income groups.

“Was it so bad,” thinks Ah Boon, “to have the disorderly parts of the world collected and sorted, put back together again in a form that one could inhabit more comfortably?”

The Great Reclamation takes readers back to a point in Singapore’s history when a compromise was made, the consequences of which have shaped the lives of later generations so irrevocably that they have never known anything different.

Heng, a millennial born in 1988, succeeds here in making those of her generation feel a profound sorrow for something they did not know they had lost.

It performs a powerful reclamation of its own, reconstructing in fiction that which has long vanished in reality.

If you like this, read: The River’s Song by Suchen Christine Lim (Aurora Metro, 2014, $39.03, Books Kinokuniya), a coming-of-age novel set against the backdrop of the Singapore River’s clean-up. Ping, the daughter of a pipa-playing courtesan, falls in love with Weng, an aspiring flautist, but they are parted as Ping goes to the United States to study, returning decades later to find her country utterly changed.