Book review: Portrait Of A Thief pulls off a post-colonial art heist

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

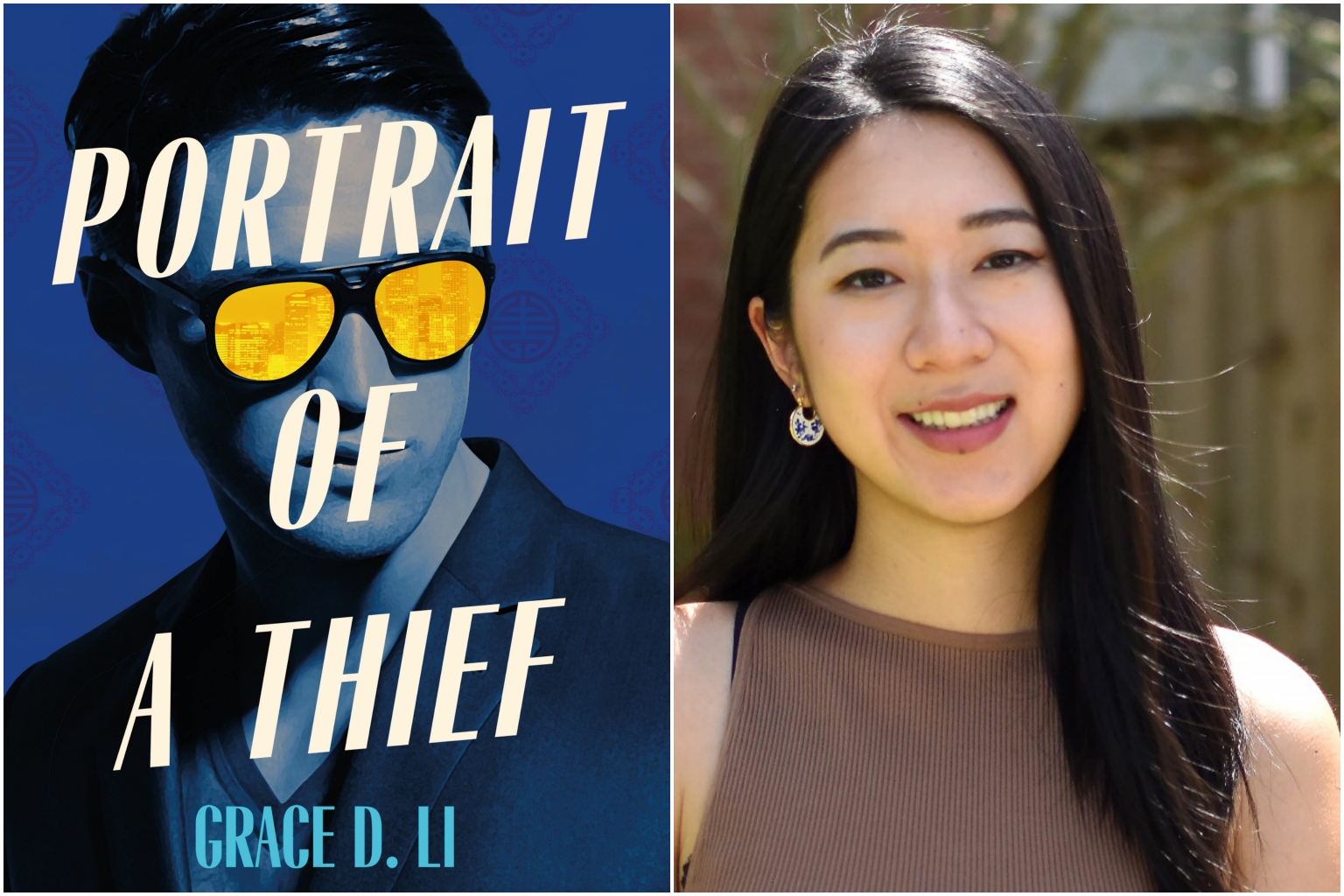

American debut author Grace D. Li's Portrait Of A Thief.

PHOTOS: TINY REPARATIONS BOOKS, YI LI

Follow topic:

Portrait Of A Thief

In 1860, British and French invading forces burned down the Old Summer Palace of Beijing and looted its treasures. Scattered across the Western world, many have yet to make it home.

American debut author Grace D. Li carries out a fictional repatriation in her crime novel with a conscience, which blends post-colonialist principles with heist high jinks.

Much of the pleasure of genre fiction comes from how it uses its archetypes. In the heist genre, it is who makes up the crew: the mastermind, the grifter, the hacker, the driver, the inside man and so on.

Li's thieves fall neatly into these archetypes, but with a twist: They are university students in their 20s, the American children of Chinese immigrants. None has ever committed a crime - or, at least, been caught for it.

When Harvard University art history student Will Chen, 21, witnesses a bold theft of Chinese art from a Boston museum, one of the thieves leaves him a note.

It leads him to a cryptic Chinese corporation and the offer of a lifetime: US$50 million (S$70.3 million) to steal five looted Summer Palace sculptures from museums across Europe and America and restore them to China.

Will ropes in his sister Irene, a public policy major who has spent years honing her gift for making the world cleave to her, and their childhood friend Daniel Liang, the estranged son of a Federal Bureau of Investigation agent.

Rounding out their team are Lily Wu, Irene's daredevil roommate who races cars by night, and Will's ex-girlfriend Alex Huang, who left Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a Silicon Valley job to help keep her family's restaurant afloat.

They are bankrolled by a mysterious billionaire, one of the wealthy young scions who belong to China's elite fu er dai.

Everything Will's team knows about heists comes from historical research or movies like Ocean's Eleven (2001) and the Fast & Furious franchise (2001 to present).

That they might succeed is improbable - but also, nobody will see them coming. And fiction may not be stranger than reality. After all, Li based her heists on a real-life string of Chinese art thefts from European museums.

Li's prose is unusually lyrical, given the genre. She writes with a painterly eye, with charcoal motion and cadmium yellow flowers, and imbues with beauty "the slow, complicated matter of peeling a museum apart".

But she is also prone to repetition to drive home her point, whether it is Will's idealism, Alex's impostor syndrome or Lily's constant urge to run away. This slows down what could otherwise be a slickly delivered story.

Her characters are caught between America and China, a foot in either culture while belonging wholly to neither.

Li is careful not to draw a clear-cut binary between East and West - the team are under no illusions that they will receive Chinese protection if they are caught, and Irene observes that China, too, can "take and take and take".

The novel does not delve further into the issue of Chinese imperialism, however, which leaves it unbalanced in its ideals.

But while the painful debate over whether museums should repatriate looted artefacts continues to rage in reality, here, at least, is some fictional satisfaction.

If you like this, read: The Gilded Wolves by Roshani Chokshi (Wednesday Books, 2018, $23.99, buy here, borrow here). In this fantasy heist set in 1889 Paris, mixed-race hotelier Severin Montagnet-Alarie assembles a team of thieves from dispossessed backgrounds to steal an ancient artefact of magic from a powerful house.

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.