Book review: Period novel Her Side Of The Story reclaims herstory in female-centric WWII story

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Her Side Of The Story by Alba de Cespedes.

PHOTO: PUSHKIN PRESS, MONDADORI PORTFOLIO

Follow topic:

Her Side Of The Story

By Alba de Cespedes, translated by Jill Foulston amzn.to/3VhZxfx

Fiction/Pushkin Press/Paperback/485 pages/$28.10/Amazon SG (

5 stars

War is seen as a masculine project initiated and fought by men.

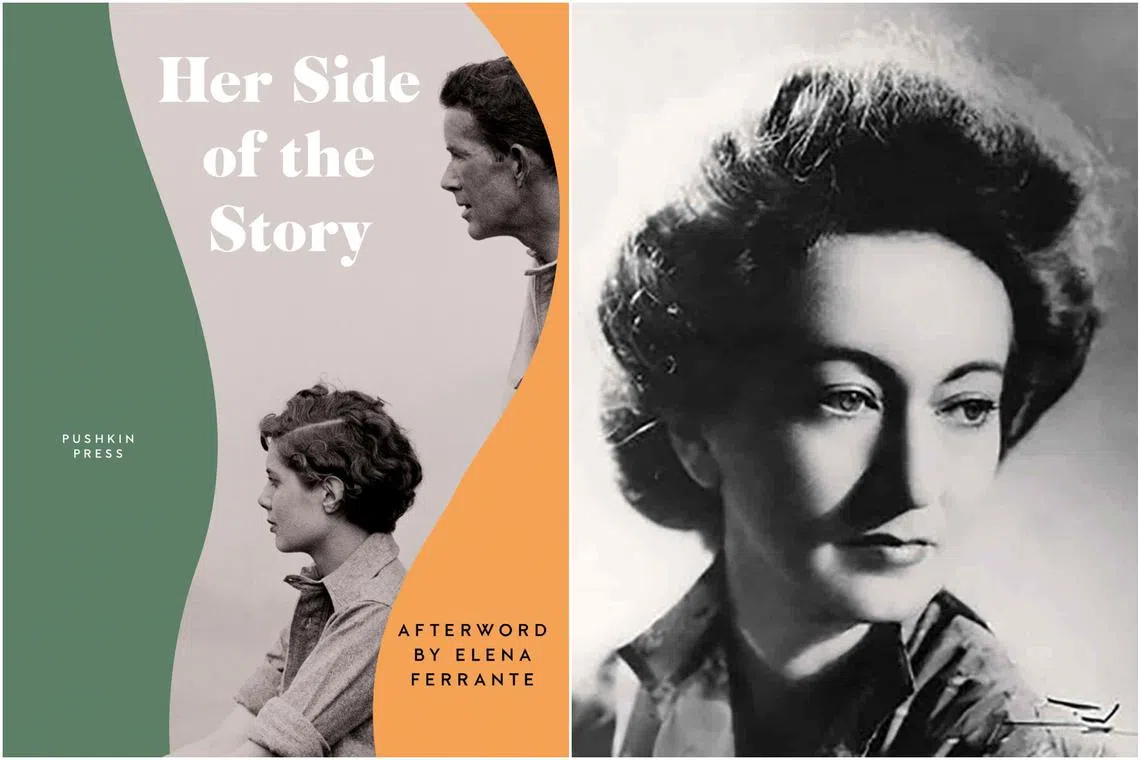

Women and children are relegated to passive casualties and illegitimate targets. Yet, in 1949, Cuban-Italian author Alba de Cespedes’ Her Side Of The Story already sought a nuancing of this narrative.

Her protagonist, Alessandra, is an active member of the resistance against the Italian fascist regime during World War II, volunteering to cycle across borders to deliver bombs while her communist husband languishes in prison.

In an extension of her effort to prove that women can be more, she overcomes fear “to continue the battle that we had been waging since my childhood”. It is not for her motivations of vainglory, or the relative shallowness of Italian nationhood. The violence, she makes clear, is a way for her to enter her husband’s world and remain close to him in his absence.

“I struggled to imagine what I would have felt if the farmers hoeing were foreigners rather than Italians,” she writes. “I felt no revulsion, no hostility, but rather, a desire to speak all languages and get along with all peoples.”

In real life, de Cespedes was a journalist who refused to lie low and hold her tongue. The granddaughter of Cuba’s first president Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, she was imprisoned twice for anti-fascist activities, and two of her novels were banned.

Amid the reconstitution of gender norms after WWII, she and her fellow women comrades were overlooked and forgotten despite their contributions, told to return to housework and tend to the children, while the men were valorised and transfigured into national heroes.

Her Side Of The Story, here translated beautifully from Italian by Jill Foulston, is about this inequality manifested in the minutiae of household relations – between father and daughter, and particularly between husband and wife.

This version by Pushkin Press hews closer to de Cespedes’ more expansive original. The previous English version, titled The Best Of Husbands (1952), was rigorously cut because she considered her novel “too rich” and the American public “very simple”.

At nearly 500 pages, this restores some, though not all, of her writing, feeling only slightly overlong towards the very end. De Cespedes writes in an explanation: “Even the brief life of a woman is infinitely long – hour after hour, day after day – and rarely is it a single motive that drives her to a sudden act of rebellion.”

This act of rebellion de Cespedes traces back to 1939, and it is the years leading up to the war before Alessandra is married that contain some of the story’s most sensitive and eloquent sentences. Still a girl, she remembers when she sees her dad embracing her mum, and for the first time feels he is an “insidious enemy”.

The ironing of his clothes – the women’s are not pressed, but left outside to get rid of the most obvious wrinkles – is transmuted into an act of female violence.

Women’s quiet camaraderie with one another in the residential block where they live is that of “people in a boarding school or a prison”.

Most lovingly detailed is Alessandra’s relationship with her mother Eleanor. She first feels betrayed by, then convinced in the necessity of, her mother’s affair. “All the misery of that intimacy established between a man and a woman was contained in the acrimonious voices I heard on the other side of the gray door.”

There is an interlude before the war in the pastoral retreat of her grandmother’s house, a more rehabilitative tonal shift where she witnesses a more pragmatic and stoic femininity.

But the unreality of her mother’s grand love haunts her, much like her drowned brother, and she is slammed back into her interiority, unable to reconcile her own belief in romance as the purpose of life with her husband’s own dismissal of it as something trivial.

De Cespedes’ framing of feminism is no longer popular. There are fundamental differences between men and women, she argues through Alessandra’s life – and “love is always stronger than they are”.

But that does not mean her depiction of reality is any less moving or fiercely insistent on equality. With every small act, slight and attempt to keep her spiralling self together, Alessandra elevates the personal to the monumental. Class and national warfare, ego and posturing – all are distractions from the bliss of hearth and home.

If you like this, read: Under A Cruel Star by Heda Kovaly (Plunkett Lake Press, 1986, $37.44, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/4bOBJ8L