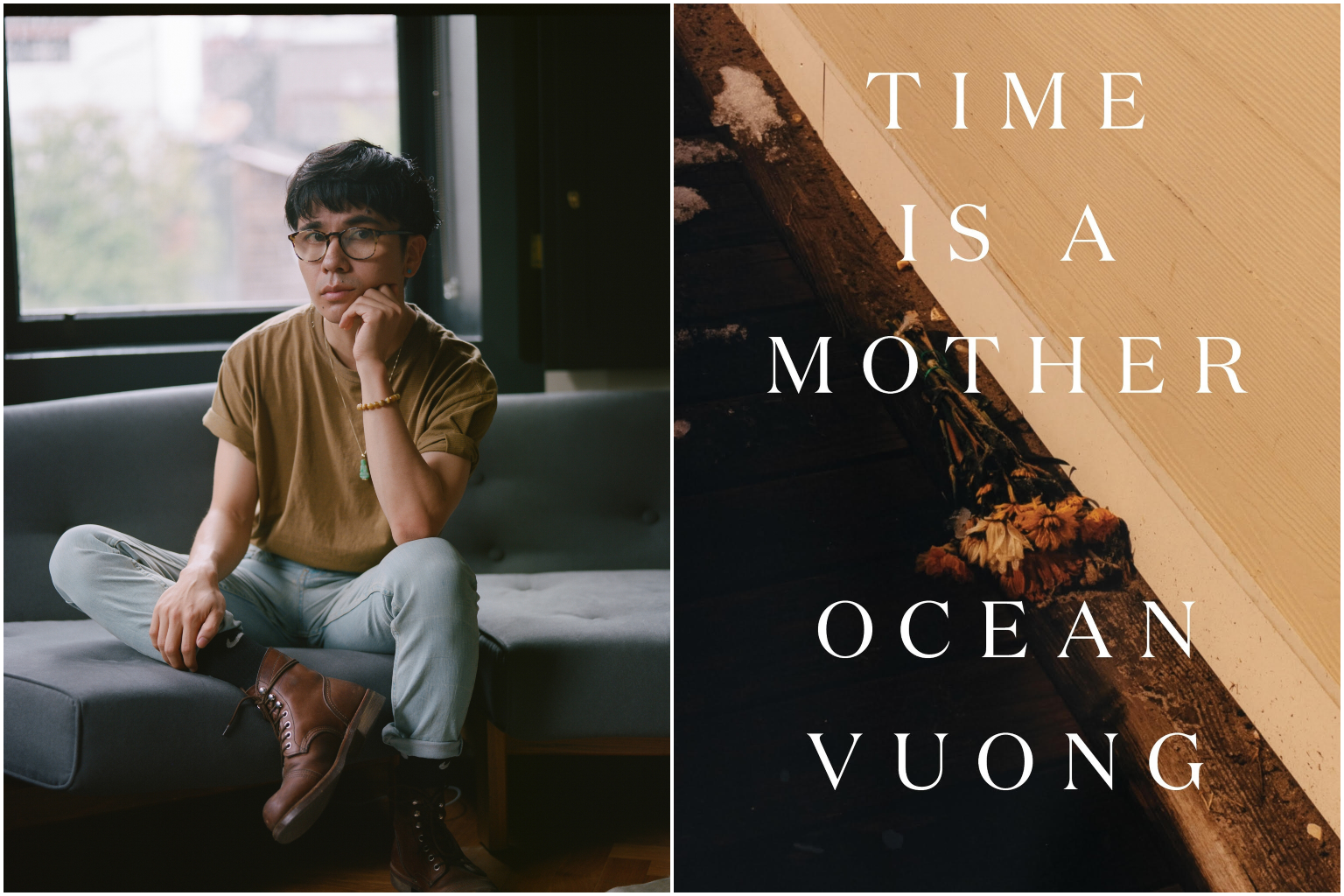

Book review: Ocean Vuong's Time Is A Mother grapples with grief and love

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Ocean Vuong's Time Is A Mother grapples with what it means to live in the wake of his mother's death.

PHOTO: NYTIMES, PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE

Follow topic:

Time Is A Mother

By Ocean Vuong

Poetry/Vintage/Hardcover/$33.95/112 pages/Buy here

4 out of 5

Poetry/Vintage/Hardcover/$33.95/112 pages/Buy here

4 out of 5

Three years after the death of his mother from cancer, Vietnamese-American poet Ocean Vuong has released a new book of poems.

His late mother Le Kim Hong ("Hong" is Vietnamese for "rose") is mentioned just a few times in the collection, but is, in many ways, its absent centre.

Vuong was born in 1988 on a farm outside Ho Chi Minh City. When he was young, his family left Vietnam, arriving in a refugee camp in the Philippines before settling in the United States.

His father later abandoned them and his mother, who was illiterate, found a job at a nail salon.

Time Is A Mother has many of the usual Ocean Vuong ingredients - intimacy, family, violence and the spectre of war in Vietnam. This book grapples with what it means to live in the wake of his mother's death.

It is more experimental than Vuong's last collection, his full-length debut Night Sky With Exit Wounds (2016), which won the prestigious T.S. Eliot Prize.

The works of Time Is A Mother range from a former nail salon worker's Amazon shopping history to Nothing, a capacious stanza - or a prose poem, call it what you will - where a loaf of rye dough is rising.

The narrator of Rise & Shine cracks eggs into a bowl and whips up an omelette with scallions and garlic "crushed/the way you/ taught me".

It is not hard to understand the appeal of Vuong, a darling of the literary world and recipient of a MacArthur "genius" grant.

His poetry, which is stark and evocative, has the accessibility of the spoken word, leans towards the confessional, and has no shortage of gorgeous sentences. The lines often lend themselves well to quotation: "I've/plagiarised my life/to give you the best/of me..."

He has a keen ear for rhythm and what poet T.S. Eliot might describe as "a precise fitness of form and matter".

Vuong feels the world with his words, holding images in his mind and letting them fold into each other in startling new ways. On the page, as in real life, his voice is soft, wistful and direct.

Even at his most self-indulgent, Vuong is self-aware.

"I want to/take care of our planet/because I need a beautiful/graveyard," says the narrator of The Last Prom Queen In Antarctica, who is "all talk... but so what".

In the poem Not Even, a woman at a Brooklyn party tells the narrator he is "so lucky" - "You're gay plus you get to write about war and stuff".

The narrator says wryly: "Because everyone knows yellow pain, pressed into American letters, turns to gold./Our sorrow Midas touched. Napalm with a rainbow afterglow.../It's been proven difficult to dance to machine-gun fire."

Not Even, like another poem in the collection, Dear Rose, is in some ways an attempt to come to terms with his mother's death.

"Time is a motherf*****, I said to the gravestones, alive, absurd./ Body, doorway that you are, be more than what I'll pass through."

Here, and elsewhere in the collection, what one gets is a sense of Vuong searching for something. Time is a mother - but of what, exactly? The poems bodied forth offer no easy answers.

If you like this, read: Night Sky With Exit Wounds (Vintage, 2016, $26.95, buy here, borrow here), Vuong's first full-length collection, which is haunted by fathers and explores loss, conflict and desire.