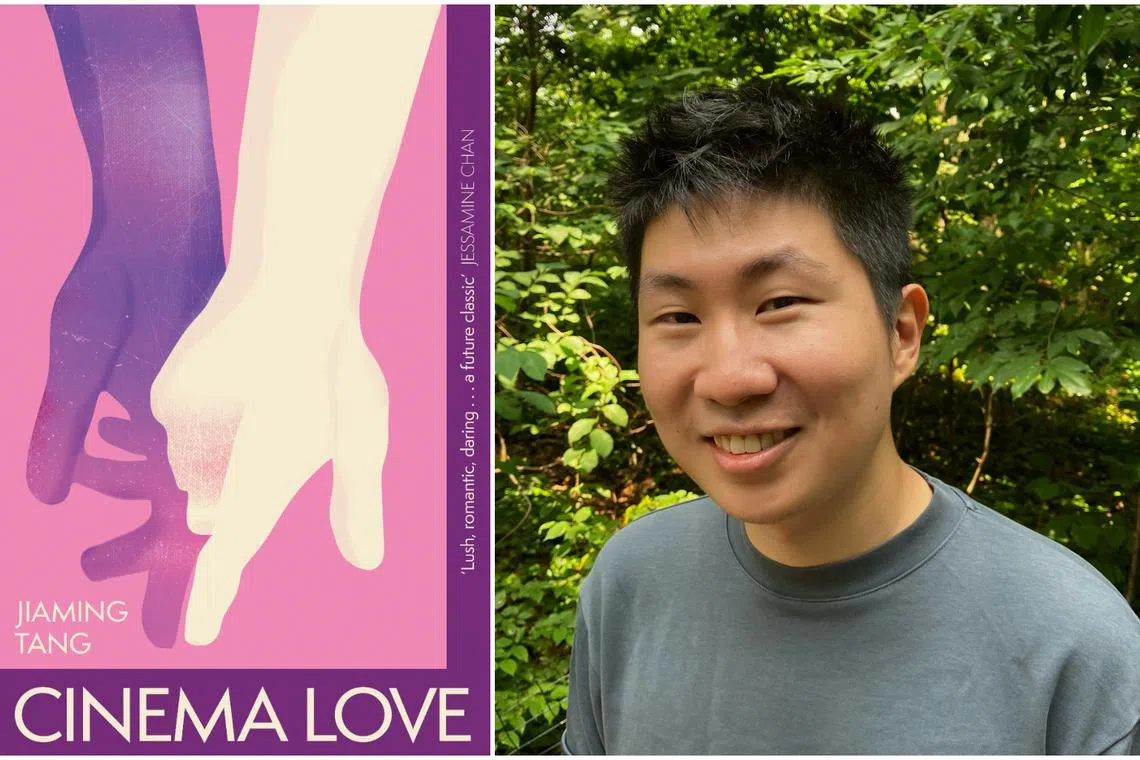

Book review: Jiaming Tang’s Cinema Love a tender swirl of double lives and loveless marriages

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Jiaming Tang’s debut novel, Cinema Love, flits between New York City’s Chinatown and rural China in a depiction of Chinese gay men's double lives.

PHOTOS: JOHN MURRAY PRESS

Follow topic:

Cinema Love

By Jiaming Tang amzn.to/3Kp9voY

Fiction/John Murray Press/Hardback/$44.50/304 pages/Amazon SG (

3 stars

A brick hurled at a gay bar in New York City in 1969 during the Stonewall riots is often cited as the impetus for America’s gay liberation movement.

Cinema Love, depicting an arson plot at a workers’ cinema for “sissy” men in 1980s rural Fuzhou, stages a similar protest. Its aftermath, however, is bloodshed and exodus.

Mawei City Workers’ Cinema is a bustling gathering point for gay men from nearby cities and faraway provinces. Here, men trade furtive glares, cruise for intimacy, gossip about former boyfriends – and hide from their wives.

Old Second, Shun-Er and Hen Bao are just some of the men playing out their double lives in the cinema.

Their wives are often aware or suspicious of their husbands’ secret lives – and Cinema Love is equally the story of these women and how they cope with secrecy, homophobia and loneliness.

The book, refreshingly, is a tender double portrait of two parties in a loveless relationship.

Brooklyn-based queer immigrant writer Jiaming Tang’s debut novel flits between New York City’s Chinatown and rural China. It tells of the journey undertaken by both men and women who leave behind their troubled pasts and hope for better lives in America, docking undocumented in their new country.

A corrective to the contemporary queer novels which tend to depict the out and proud, Tang casts his eye to the shadows.

The novel zooms into the microscopic worlds of gay subculture in Fuzhou, Chinese diasporic enclaves in New York and crowded family homes.

Cinema Love follows multiple characters in a multitude of relationship arrangements. Most interesting is gay man Old Second’s lavender marriage – a marriage of convenience to hide one’s sexuality – with the cinema’s ticketing lady Bao Mei as they move to New York. Partly a ghost story, floating spirits of gay men also haunt these characters in China and America.

Tang handles the tense negotiations of relationships well, but his depiction of furtive desire falls short.

Novels like American novelist Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs To You (2016) and English novelist Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library (1988) are obvious points of reference in the genre, and Tang’s prose is not quite in that league.

A tendency to make the feelings of his characters overly legible through an over-explaining third-person narrator thwarts any possibility of subtext and implication. Dialogue, too, can sometimes be plain and obvious: “The Workers’ Cinema, it let us feel what other men felt in the daylight. Our love wasn’t flowers but the sprouting of old vegetables.”

The book brings to mind Taiwan-based Malaysian film-maker Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), which depicts a dilapidated cinema charged with sexual energy.

In Tsai’s masterful and mostly silent film, nothing is explicated. Tang’s novel, on the other hand, can benefit from more restraint.

The novel leaves one wanting more interiority, but Tang has also created a fascinating, rarely revealed world in this well-plotted debut. The book’s tender swirl of stories depicting the lives of men and women caught between two lives has its touching moments.

Cinema Love, aptly, is the kind of fast-paced, sprawling novel ripe for a film adaptation.

If you like this, read: In The Face Of Death We Are Equal by Mu Cao, translated by Scott E. Myers (Seagull Books, 2020, $22, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/4bPfNtU

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.