Book review: Jesmyn Ward’s harrowing Let Us Descend enters the hell of American slavery

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

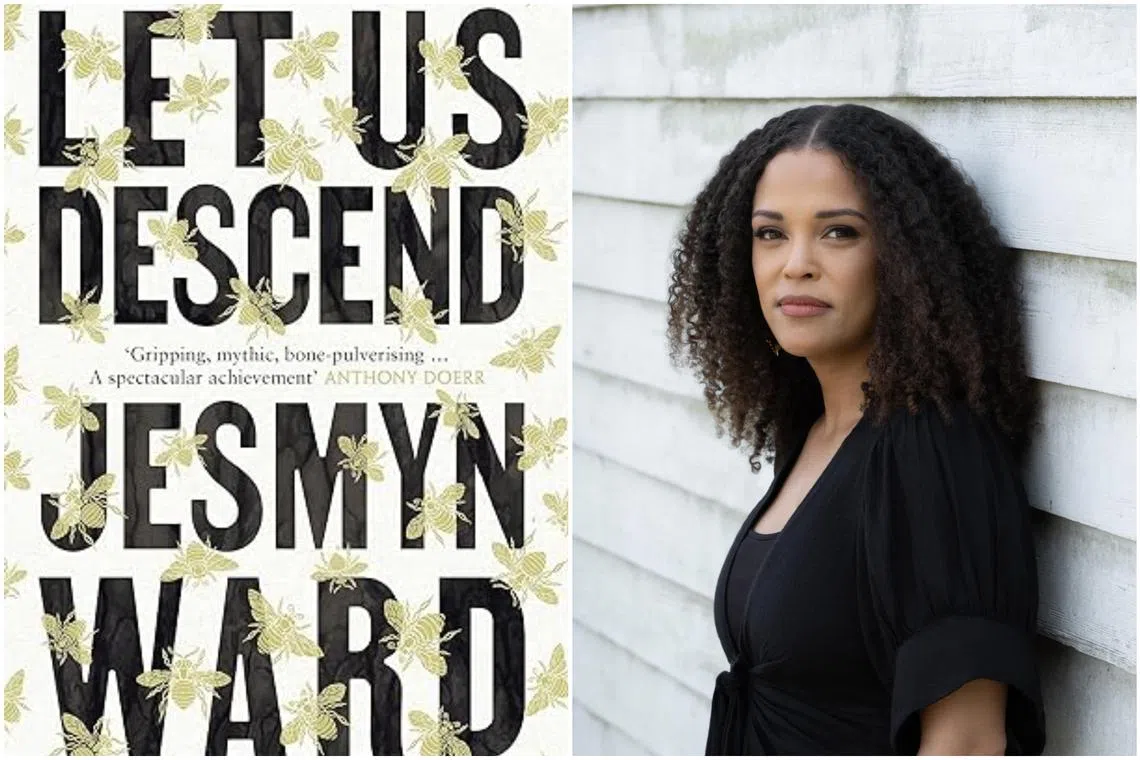

American author Jesmyn Ward turns to history for Let Us Descend, the title of which alludes to the hellish descent in Dante’s 14th-century epic Inferno.

PHOTOS: BLOOMBERG, BEOWULF SHEEHAN

Follow topic:

Let Us Descend

By Jesmyn Ward amzn.to/3U2wrjX

Fiction/Bloomsbury/Hardcover/303 pages/$38.41/Amazon SG (

4 stars

In his pioneering 1845 memoir, the former slave Frederick Douglass recalls a horrific childhood memory of watching his aunt get whipped by their master.

“It was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery, through which I was about to pass,” he writes.

This line by Douglass, who in penning his own narrative helped prove the intellectual capacities of African-Americans, finds its echo in American author Jesmyn Ward’s Let Us Descend.

Ward, a two-time National Book Award winner, has depicted with exquisite devastation the lives of working-class African-Americans in rural Mississippi.

She turns to history for her fourth novel, the title of which alludes to the hellish descent in Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century epic Inferno.

Ward’s narrator, Annis, hears snatches of this poem as she eavesdrops on a tutor reciting Dante to her half-sisters. Unlike them, Annis is enslaved, conceived when her plantation-owner father raped her mother.

She muses that the hell Dante travels “has levels like my father’s house”. Instead of the abstract inferno of the ancient poem, the hell of slavery is a very real one in which she and her mother toil.

By night, Annis’ mother teaches her in secret to fight like her grandmother, a Dahomey warrior who was sold into slavery after she fell in love with the wrong man, thus beginning the tragic plight of their line. The novel opens with Annis’ powerful statement: “The first weapon I ever held was my mother’s hand.”

When her father attempts to rape her too and her mother intervenes, he sells her mother. In grief, Annis starts a secret affair with another enslaved girl, Safi, only for her father to sell them both.

So begins her descent into a historical hell, a horrifyingly brutal cross-country march to New Orleans, which looms as “the grief-wracked city” of an infernal landscape.

Ward draws on African mythology to populate this landscape with ravening spirits, from They Who Take and Give, who inhabit the devouring earth, to the river that tries to drown Annis in each crossing.

Annis’ mercurial guide through this hellscape is Aza, a tempestuous, fickle storm spirit who takes the name and form of Annis’ grandmother, but has her own agenda.

Haunted by memories of her mother, Annis must decide if she should give herself over to worshipping Aza or if she has the strength to carve her own path.

Ward maps a harrowing path through a senseless hell of humanity’s own making. The amount of suffering in this novel is relentless, verging on repetitious. In its final stretch, however, it becomes transcendent.

As in Inferno, the heroine emerges from hell to a sky full of stars.

If you like this, read: The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates (Oneworld, 2020, $19.26, Amazon SG amzn.to/3Hhu3OV