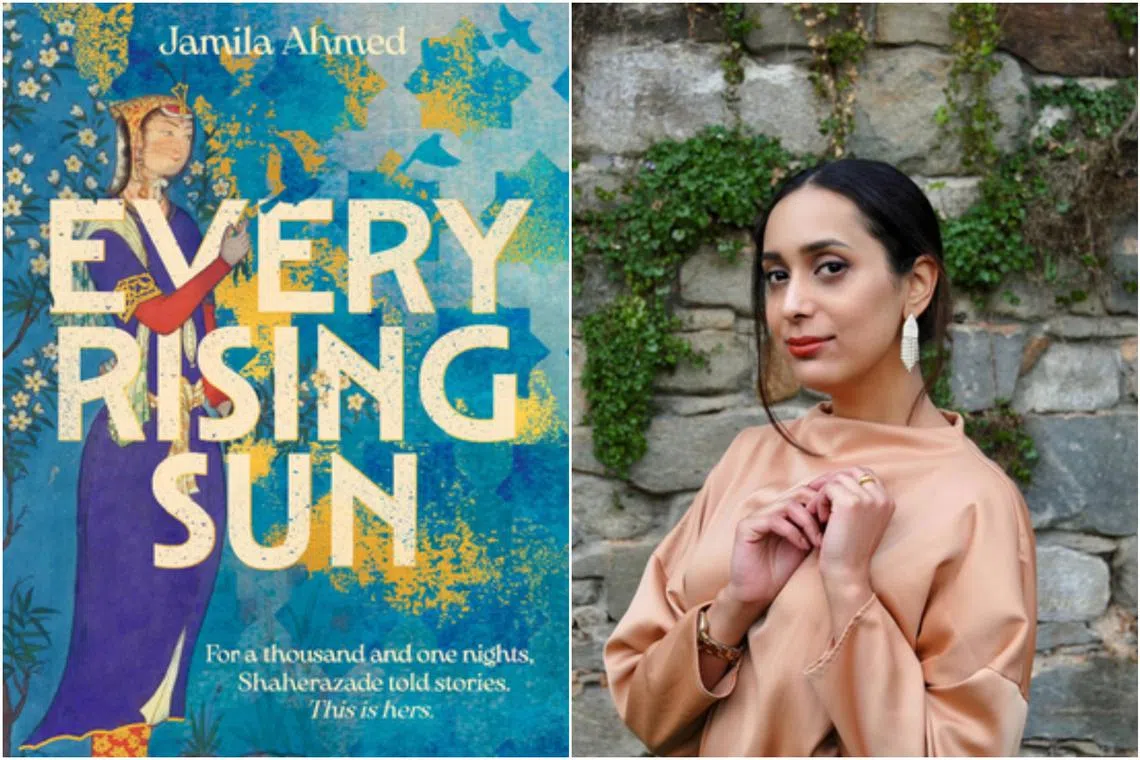

Book review: Jamila Ahmed’s Every Rising Sun an uneven retelling of Arabian Nights

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Every Rising Sun by debut novelist Jamila Ahmed remakes Arabian Nights with a feminist focus.

PHOTOS: JOHN MURRAY, LEWIS MAY

Follow topic:

Every Rising Sun

By Jamila Ahmed amzn.to/3KJHZTL

Fiction/John Murray/Hardcover/416 pages/$30.70 from Amazon SG (

3 stars

This debut novel by Pakistani-American lawyer Jamila Ahmed places the famous storyteller of the Arabian Nights front and centre. Shaherazade, as her name is spelled in this take, is an inveterate bookworm, a lover and spinner of tales whose own story anchors this feminist reinvention.

The idea is sound but the execution less so as the narrative displays both the strengths and weaknesses of a first novel.

Where Ahmed, a mediaeval Islamic history scholar, excels is in creating the textures of the cosmopolitan and varied Islamic world Shaherazade inhabits.

The original One Thousand And One Nights was an anthology – spanning Middle Eastern, Indian and even African stories – collated by various scholars over the centuries, with the earliest fragment dating back to the ninth century.

Jamila has chosen a more specific time and place to anchor her story: 12th-century Kirman, a Muslim-Persian province then ruled by the Seljuks.

This sets her story towards the end of the Islamic golden age, when creative writing and scientific thinking flourished, and trade and commerce fed Islamic courts with luxury goods.

The author describes in sensuous detail the vibrant sophistication of this world from the first line of the book: “It is said that in the province of Kirman, a land of green pistachios and dusty mountains, reigned a Seljuk Malik called Shahryar, who wed a pearl-skinned beauty named Fataneh.”

The lavish wedding immerses the reader immediately in a vivid other world.

“Turquoise tiled arches swooped like snowy swan necks, and silver and gold lanterns glowed overhead with a soft, firefly light”. Smells “light and herbal – anglica, nigella” compete with “more eye-watering scents – esphand and frankincense”.

Even in a smaller provincial court, guests are draped in bright silks and dine on “hare spiced with thyme, saffron-scented rice, pullet stew simmered in ginger and rosewater”.

The event is observed by a 10-year-old Shaherazade, the older of two daughters of a high-ranking official, starry-eyed with girlish ideals of romance.

But the initial fairytale dazzle soon dims into darker shades: “And this is not an empire founded on mercy. Mothers put out their princes’ eyes, sultans poison wives and atabegs force maliks to spin to their command.”

An older Shaherazade accidentally discovers Fataneh’s fatal secret – the latter has been unfaithful to Shahryar, who is the malik or king. Shaherazade – in choosing to survive – betrays Fataneh by tattling anonymously to Shahryar. He promptly beheads his wife, and settles into the bloody ritual of wedding, and beheading, a series of new brides.

Shaherazade, horrified by the consequences, decides to marry Shahryar to prevent more slaughter. Her love of narrative becomes her defence and her weapon as she uses fables to delay her own death.

There is, of course, plenty of material to be mined from restoring Shaherazade’s voice. Unfortunately, Jamila might have bitten off more than she can chew.

Even as Shaherazade’s fables weave a fabulous fictional web around not just Shahryar, but also the reader, the momentum of the narrator’s own life story stalls.

In an attempt to amp up the stakes, Jamila introduces political and military intrigues.

Shahryar’s beheading of brides causes unrest in his realm and Shaherazade’s intervention stops not just serial murder, but quells political unrest. Shahryar also rides out of Kirman with an army to join the legendary Saladin in his military campaign against the Frankish crusaders.

While these plot machinations root the tale in historical soil, they also prove unwieldy. It does not help that there are multiple romantic subplots for Shaherazade’s sister Dunyazade and assorted female attendants.

What suffers is Shaherazade’s character development. There are occasional hints of her ambitions and desires in throwaway lines. But the need to wrangle a multi-threaded narrative results in an annoying deus ex machina as the author tries to tie up loose ends in the last quarter of the book.

There are myriad pleasures to be gained from this retelling, chiefly in its loving portrait of a dynamic Islamic world as well as the interstitial fables that recall the magical fairytales of the original. But Shaherazade remains a narrative device, a channel for other more intriguing stories.

If you like this, read: The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales From 1001 Nights, translated by Yasmine Seale (Liveright, 2021, $44.26, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3OGTe0B

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.