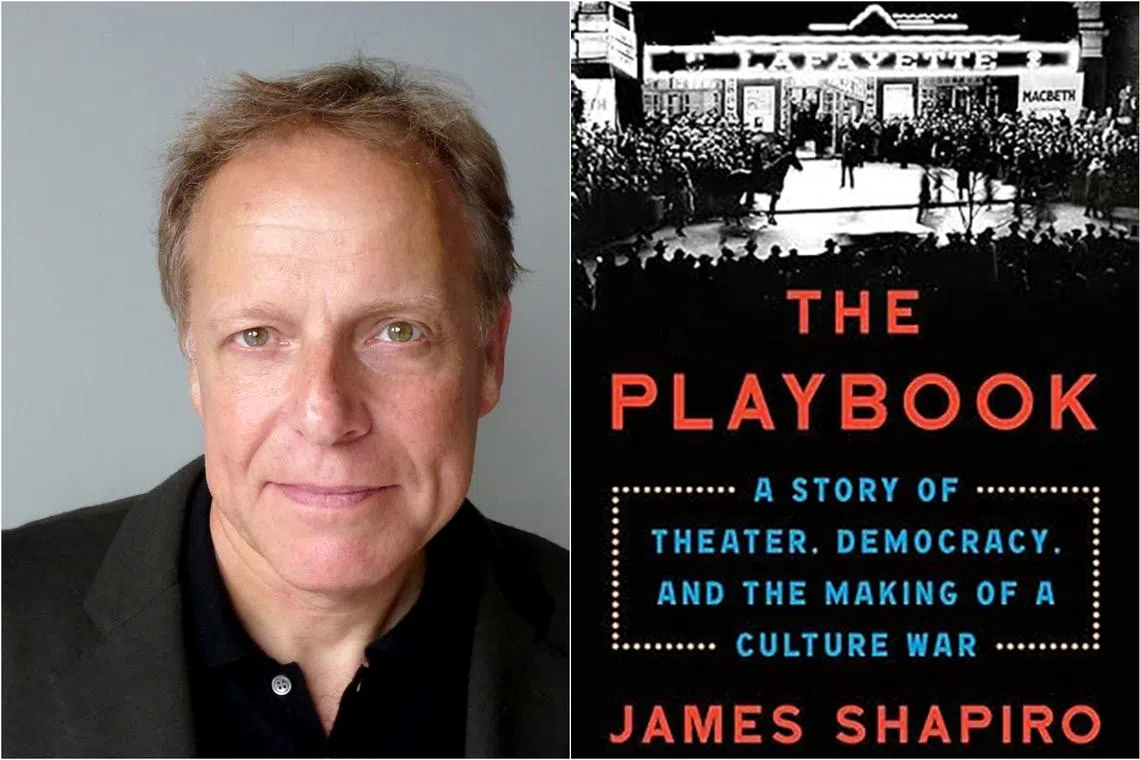

Book review: James Shapiro’s The Playbook narrates theatre and culture wars in 1930s America

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The Playbook by James Shapiro explores the birth and trajectory of the United States' Federal Theatre Project in the aftermath of the Great Depression.

PHOTOS: FABER & FABER

The Playbook

By James Shapiro amzn.to/3KvhqkD

Non-fiction/Faber & Faber/Hardcover/342 pages/$40.04/Amazon SG (

4 stars

Something theatrically anti-theatre happened in 1939. The ending of Pinocchio, the United States’ latest Broadway hit, was changed so the puppet boy dies, killed by an “act of Congress”.

Stagehands knocked down sets in full view of the packed house. The fantastical creation of Italian writer Carlo Collodi had become the stand-in for the very real demise of the Federal Theatre Project, instituted by President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and which once employed some 12,000 struggling artists in the US, including American film-maker Orson Welles and playwright Arthur Miller.

Baillie Gifford Prize winner James Shapiro’s latest book uncovers the precarious birth of America’s first Federal Theatre Project in the aftermath of the Great Depression, and its subsequent targeting by Congress amid the culture wars in the lead-up to World War II.

The title, The Playbook, draws a straight line from the tactics waged by congressman Martin Dies – who presided over the House committee investigating “un-American” activities that sounded the death knell of the project – to those later employed by senator Joseph McCarthy and former president Donald Trump.

This is not some esoteric chapter in American theatre history, as Shapiro keenly notes. There have been repeated assaults on the budget of the National Endowment For The Arts since it was signed into existence by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, whether from former president Ronald Reagan or more recently from Trump and House speaker Newt Gingrich.

Even now, a bill to reduce its funding to zero has been submitted by congressman Andy Biggs of Arizona, a leading member of the far-right House Freedom Caucus. Theatre, with its progressive values and open-endedness to multiple interpretations, has always been a soft target for those looking to score easy points for upholding “patriotic” politics and “decent” lifestyles.

Shapiro – partially using a treasure trove of set designs, posters, programme notes and photographs found covered in pigeon poop in an aeroplane hangar in Maryland in 1974 – sketches an intriguing story.

Reproducing debates in the US Congress and the fraught exchanges during the public examination, he illuminates Dies’ now well-worn tactics of reframing testimonies and grandstanding.

Blow-by-blow accounts reveal his prescient grasp of what would make the most sensational headlines, even sometimes allowing his son to come on the dais to light his cigar or play with his gavel to entertain reporters.

There is the familiar stupidity – a member’s ignorant question of whether 16th-century playwright Christopher Marlowe was a communist drew laughs from onlookers. None of those asking the questions had watched a Federal Theatre Project play.

But the overall reality is decidedly scary. “As long as he kept a fresh stream of accusations coming, this press wouldn’t have time to investigate unsupported allegations,” Shapiro writes of Dies. “All the ammunition (it) needed would be an improper prop or poster, or evidence that it was somehow, by oppressing dictatorship, promoting communism.”

Shapiro is clear-eyed about the limitations of a national theatre that relied on the government for grants and the compromises this involved. The Federal Theatre Project was initially created to help theatremakers get back on their feet, buffeted by the Great Depression and the rising star of cinema.

Yet, project director Hallie Flanagan was more idealistic, believing that a theatre that engaged with modern problems was the way forward.

She was a strong proponent of the Living Newspaper form, which portrayed up-to-date news events and conveniently employed large casts to fulfil its employment aims.

Federal Theatre Project plays also often shifted matinee hours so the working class could attend. The same play could be regionalised. One Third Of A Nation, about the public housing crisis, could be given extra oomph by changing to black actors or substituting a disastrous fire with a building collapse.

Yet, even some touchy questions were beyond Flanagan, and some of the best passages are those analysing how the Federal Theatre Project half-heartedly tried, but ultimately failed, to tackle matters of race, with the Jim Crow laws still in place.

Its first hit was also the high point of its impact in this direction. A voodoo Macbeth in 1936, directed by Welles and played by an all-black cast, transported the action to Haiti and had American travel writer Martha Gellhorn remarking that the audience composition resembled “a checkerboard”.

It was a temporary expansion of the roles black actors could play, but they would pass into obscurity. Welles and co-director John Houseman would take much of the credit for this play that still pandered to the white gaze.

Shapiro makes the point that in the Federal Theatre Project’s lifespan from 1935 to 1939, no play directly confronting racism was staged, with Liberty Deferred – a story including a place called Lynchotopia, where black victims of lynching met – scuttled by the Federal Theatre Project’s own personnel.

American publisher The New Republic’s literary editor Malcolm Cowley wrote of the Federal Theatre Project that “the progressives had their chance and most of them lost it... too busy quarrelling among themselves that after grasping it they let it slip from their hands”.

It is up to those living now to take the chance and give it the greatest push forward they can muster.

If you like this, read: The Soul Of America: The Battle For Our Better Angels by Jon Meacham (Penguin Random House, 2018, $25.03, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/4c3j9cE

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.