Book review: In Blaise Ndala’s In The Belly Of The Congo, a 1958 human zoo haunts the present

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

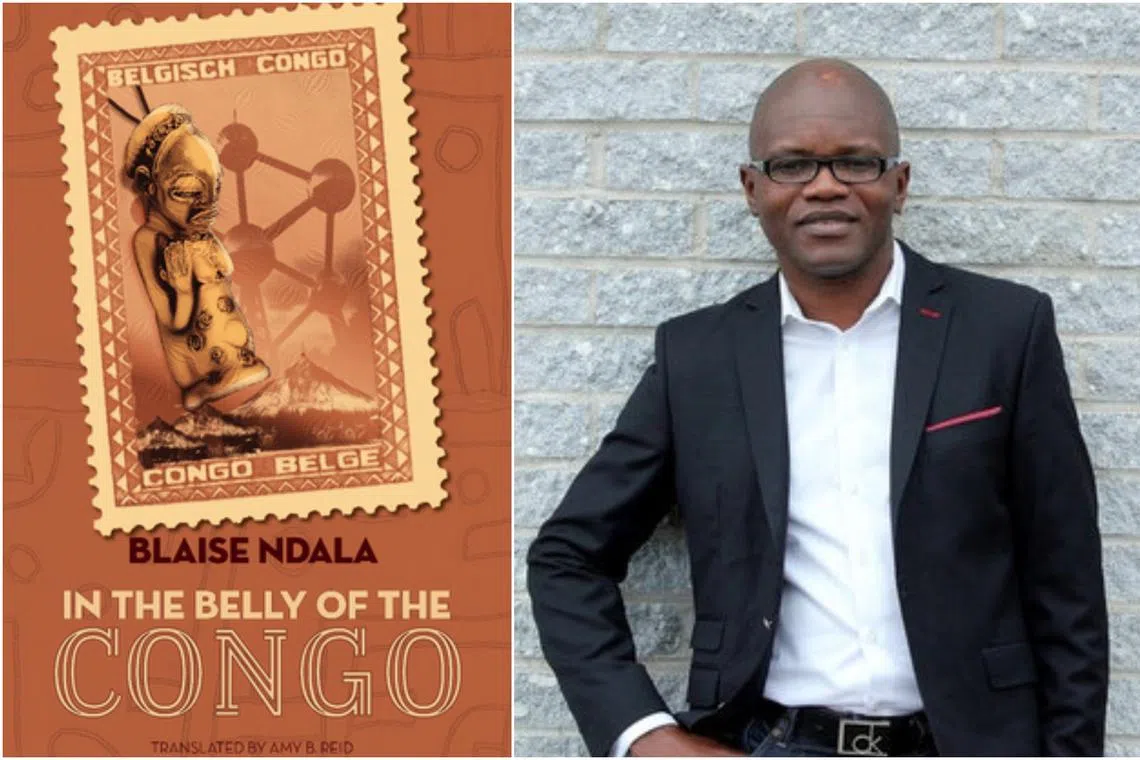

In The Belly Of The Congo By Blaise Ndala, translated by Amy B. Reid.

PHOTOS: PASCALE CASTONGUAY,OTHER PRESS

Follow topic:

In The Belly Of The Congo By Blaise Ndala, translated by Amy B. Reid

Fiction/Other Press/Paperback/368 pages/$28/Amazon ( amzn.to/3PIGQiE

4 stars

At the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, a Congolese village – a live display of more than 700 men and women – was exhibited in the Belgian capital for visitors to gawk at.

It was to be the last human zoo in history, and ostensibly one of the final crimes committed by the Belgian colonial empire before its colony gained independence as the Republic of the Congo in 1960.

But Canadian writer Blaise Ndala, who was originally from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, has an eloquent way of locating history in the present.

In his first novel to be translated from French into English, he opens up this fraught historical moment and spins it into a tale of how the colonial past continues to haunt the supposed freedom of the present.

In The Belly Of The Congo is an epic and often digressive tale that composes a compelling narrative about a violent museological act in 1958 and its reverberations in the supposedly post-colonial Congo of the new millennium.

Ndala, in his typically satirical voice rendered through Amy B. Reid’s fluid translation, draws a further historical connection when the Belgians rationalise the idea of a human zoo in 1958: “We will in no way reproduce the village of 1897. This is the twentieth century.”

His protagonists are two women with the same name, separated by the gulf of half a century. Princess Tshala Nyota Moelo, daughter of King Kena Kwete III of the Kuba people, is one of the human subjects brought into the Congolese village in 1958 who subsequently disappears from history.

In 2003, the other Nyota tries to locate her aunt’s story. But her quest for historical truth, in a twist of fate, binds her to the same predicament of her forebears half a century earlier.

Nyota, recruited to be a skimpily clad model at a large car show in Brussels in 2003, is admonished: “If you, a Congolese woman, were interested in the history of your adoptive country, you’d know this place already exhibited something far worse than the beautiful a** of an African hostess, believe me.”

Parallel storylines that run across different eras of Congo’s history give the story a variegated texture that lend intrigue and mystery to how Ndala will reveal the unlikely resonances through history’s corridor.

His playful use of perspective, with some sections are narrated from the grave, demonstrate how inadequate colonial institutions like state archives can be when attempting to uncover a suppressed history.

The novel is sometimes bogged down by too many extended monologues by more than a handful of characters.

A cast of historical figures, from the idolised Patrice Lumumba – the first president of the Republic of the Congo – to the father of the Congolese rumba Wendo Kolosoy, anchors the novel in reality, and is a riveting tour of the real characters who shaped the Congo in its tumultuous history.

In an age where institutions such as the museum, the archive and the exhibition are under examination for their colonial baggage, Ndala’s novel offers a human story about how an ostensibly bygone era’s violence continues to shape the very institutions that people view as enlightened today.

If you like this, read: Season Of Migration To The North by Tayeb Salih and translated by Denys Johnson-Davies (Penguin Books, 2003, $13.90, Amazon, go to amzn.to/43f3AtC

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.