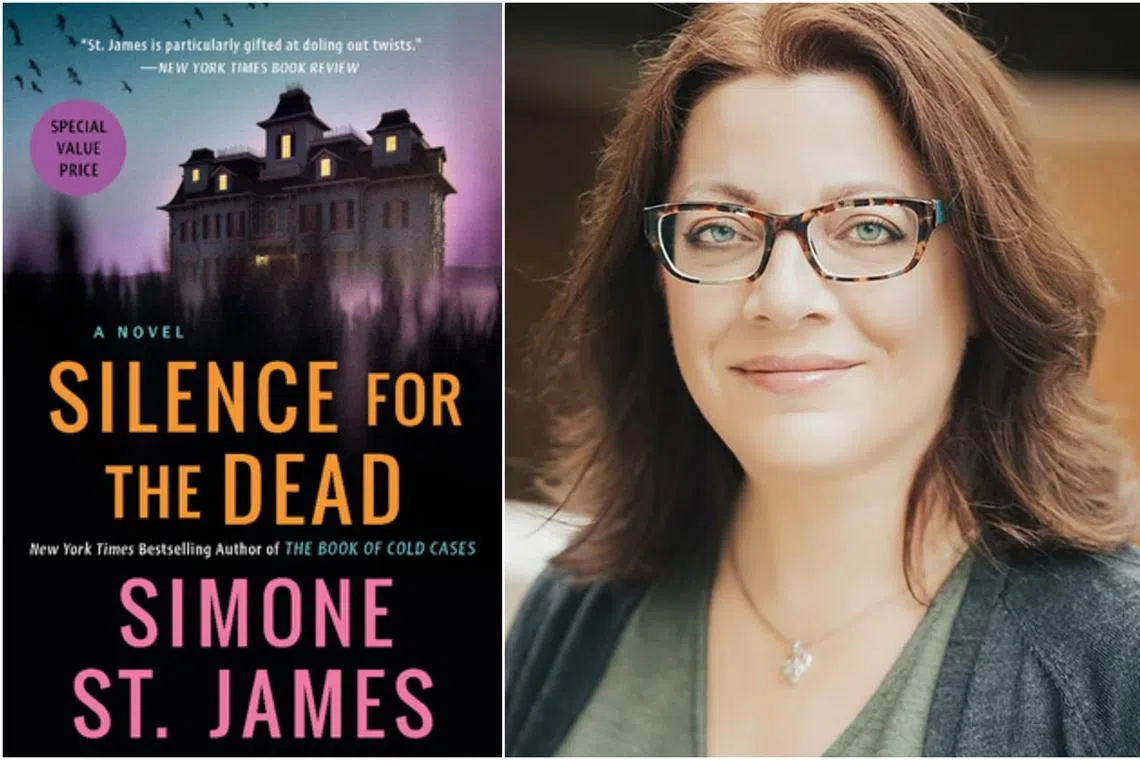

Book review: House of horrors in Simone St James’ Silence For The Dead tackles post-war trauma

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Silence For The Dead By Simone St James.

PHOTOS: TIMES DISTRIBUTION, LAUREN PERRY

Silence For The Dead By Simone St James

Fiction/Berkley/Paperback/372 pages/$14.21/Amazon ( amzn.to/3QuG0Gu

4 stars

Barely 20 years old, Kitty Weekes thinks she has pulled off a coup when she secures a job as a nurse at isolated Portis House with no relevant experience.

But any sense of victory quickly goes out the window when she is asked to scrub a toilet that periodically secretes strange black goo.

Suddenly, the hospital-wide ban on smoking that she had found so offensive when she was inducted seems the least of her problems.

From Canadian mystery writer Simone St James comes this fun tale set in a convalescence house for World War I soldiers in England, 1919.

Readers who worry that the strange happenings in the house might remain as metaphors for the crumbling minds of these veterans can rest assured – there are literal ghosts and there is even a little bit of the energy of Netflix hit Stranger Things (2016 to present) in Silence For The Dead’s fantastical construction.

Like British author Diana Wynne Jones, St James has the ability to write for (precocious) children while involving enough thematic rigour for adults to also make a fulfilling time of her stories.

Beneath the crowd-pleasing twists, there is an undercurrent of serious intent mixed with some imagination, generating a fable that is not exactly for modern times, but still has pertinent things to say about traditional modes of masculinity.

The target, naturally, is post-traumatic stress disorder and the toxic sense of emasculation plaguing these soldiers at the unhinging of their minds.

It causes them to self-deprecate in good humour, but also lash out and feel ashamed. Nurse Weekes is sexually harassed on her first day.

The professional competition between the female nurses for the attention of the inevitably male doctors – the only rank that matters in the house – reveals much of the difficulties of female empowerment and solidarity at a time when the judgment of men alone determines one’s career advancement.

St James almost casually inserts her most incisive observations. Girls who are engaged and about to leave the profession enjoy the highest status in the group of women.

Weekes, like most of the soldiers’ lovers and families, begins unsympathetic to the patients, who she cannot help but think are weak for losing their grip on reality after serving their king and country.

She herself is a survivor of trauma, yet a meeting with confidential patient No. 16, Jack Yates – a working-class hero for England during the Great War, who has checked himself into the facility after a suicide attempt – leads her to question her own assumptions.

The subsequent romance that blossoms between the two is the stuff of young-adult fiction, but the inquisitive Weekes and the assured Yates make for natural allies in confronting the horrors of the house.

Fearful of being labelled as crazy, the patients have found it easier to simply not talk about the common nightmare that plagues their dreams. St James smartly uses the idea of possession as a neat excuse for the men to abjure responsibility for their actions, as they might have done during the war.

It is only when they open up about this, however reluctantly, that they can begin to uncover the larger-than-life story that transpired at Portis House.

To live, they have to talk. Silence is for the dead.

If you like this, read: Fire And Hemlock by Diana Wynne Jones (Methuen, 1984, $23.81, Amazon, go to amzn.to/47hibrW

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.