Book review: Haruki Murakami plays the hits

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

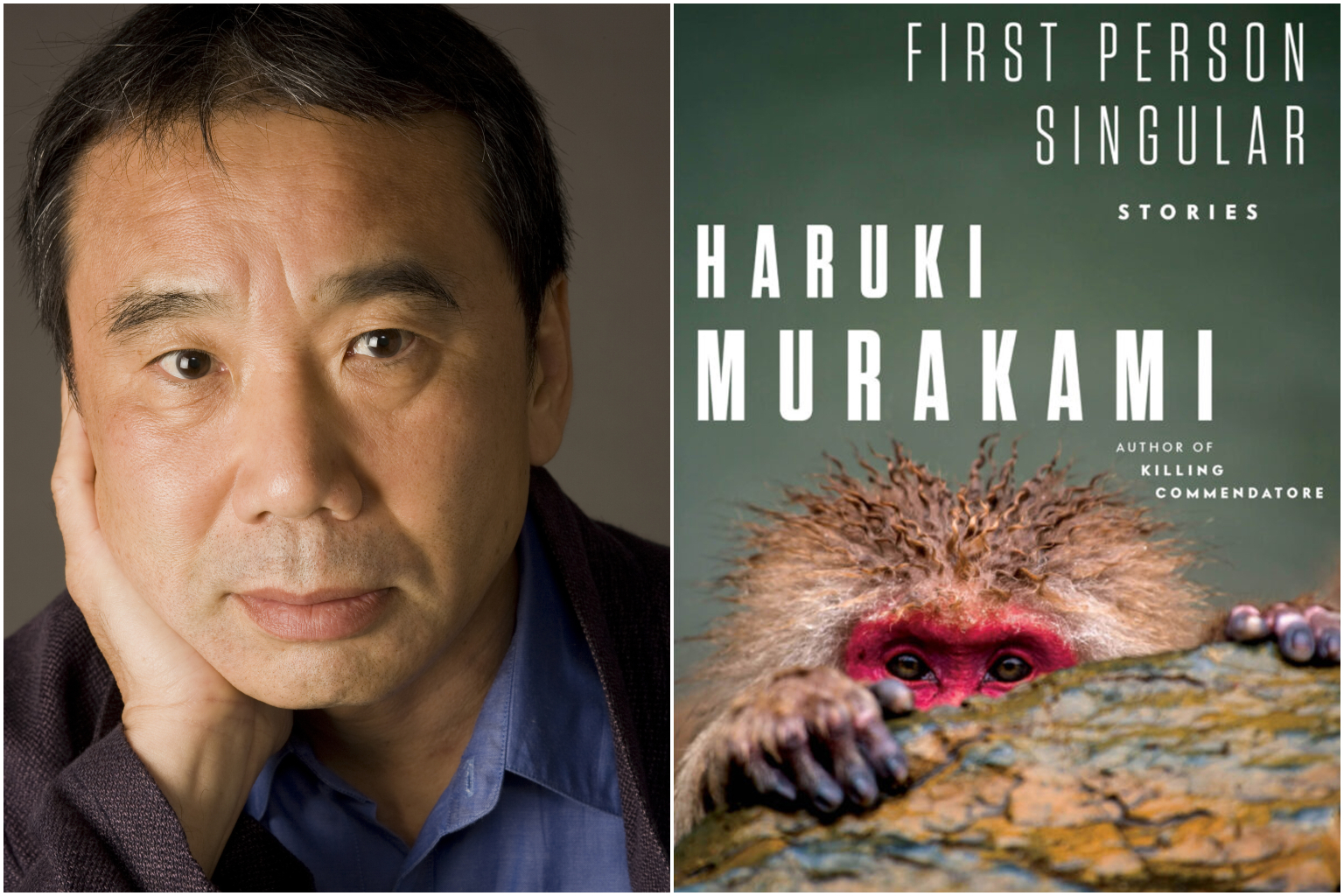

First Person Singular is classic Haruki Murakami (left), whose very name evokes an entire aesthetic of surrealist nostalgia.

PHOTOS: ELENA SEIBERT, ALFRED A. KNOPF

Fiction

FIRST PERSON SINGULAR

By Haruki Murakami, translated by Philip Gabriel

Alfred A. Knopf/ Hardcover/ 246 pages/ $37.95/ Available here

3 out of 5

There is a pattern to the Murakami short story. Usually, it begins with a deceptively ordinary incident, like being invited to a piano recital, or writing a jazz review for a college paper, or stopping for the night at a hot springs inn.

Then something tilts, and the world is ever so slightly aslant. The recital venue is padlocked and abandoned. The record in the review does not actually exist. The door of the hot springs bath slides open and a monkey walks in and says, "Excuse me."

First Person Singular is classic Murakami, whose very name evokes an entire aesthetic of surrealist nostalgia. His tropes have tropes.

This collection gathers eight of the Japanese author's short stories, most of which have been published individually elsewhere. They are all told in the first-person singular and could be fiction or memoir - though the author seems happy to elide such distinctions.

The piece with the strongest claim to memoir is The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection, in which the narrator expounds on his love of baseball and how he would sit in the outfield seats of Jingu Stadium and scribble down poems of the so-bad-they're-good variety.

One, Outfielders' Butts, waxes lyrical about the players' derrieres - the better ones, that is.

"I was about to list

The names of outfielders whose butts

Are not what you'd call attractive -

But decided I'd better not.

After all, you have to consider their mothers and siblings, and wives

And kids, if they have any."

It is hardly scintillating verse, though as Murakami so rarely turns an objectifying eye on the male form rather than the female, this reviewer finds it utterly hilarious.

The prose has a way of moving like freestyle jazz, slipping, catching, wheeling off again. Accordingly, the stand-out stories are those most attuned to music, like With The Beatles, which grasps at memory and meaning. No Murakami book is complete without a Beatles reference.

In Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova, the collection's best, the narrator reviews a jazz record he invented for a college publication. In reality, jazz legend Charlie "Bird" Parker died before bossa nova hit the big time. He gets resurrected in this dreamy piece that totters on the brink of indulgence, but is saved by Murakami's facility for the language of music.

Murakami is clearly coasting with these fleeting, enigmatic stories, about which there is nothing very singular. If they were a record, you could put it on in the background, something vaguely charming to while away the time until the next big hit comes along.

If you like this, read: Men Without Women by the same author, translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen (Vintage, 2014, translated 2017, $17.66, available here), a collection of stories about men who have lost women in their lives, either to other men or death.

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.