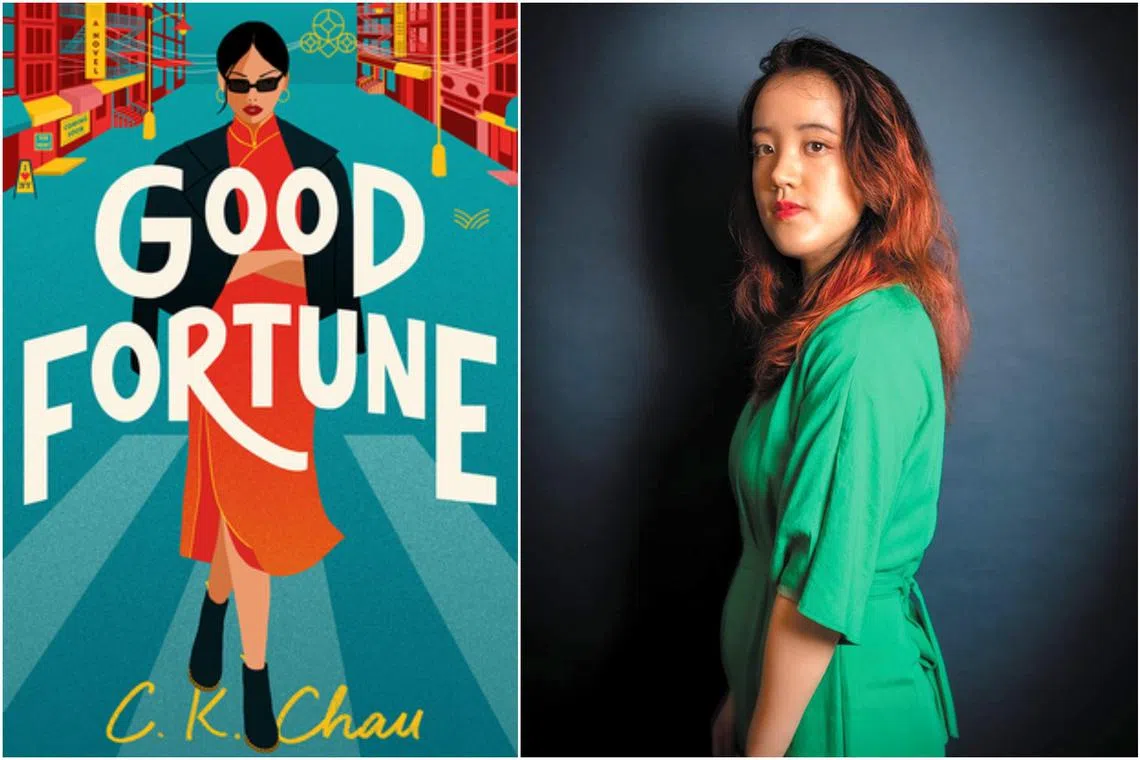

Book review: C.K. Chau offers a rollicking update of Pride And Prejudice in Good Fortune

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Good Fortune is no mere cookie-cutter copy of Pride And Prejudice, but a satisfying meal unto itself.

PHOTOS: HARPERVIA, COURTESY OF C. K. CHAU

Follow topic:

Good Fortune

By C.K. Chau amzn.to/47P0Qqv

Fiction/HarperVia/Hardcover/404 pages/$41.60 from Amazon SG (

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice, in possession of excess wit, will perennially be raided by authors in want of inspiration.

The good news is that C.K. Chau rises above mere plagiarism to offer – gasp – a shockingly fun update.

Austen’s genteelly impoverished Bennet family gets transplanted from 19th-century Hertfordshire to early 2000s New York Chinatown as the distinctly blue-collar Chens.

The five Chen siblings – “what bad luck, all of them girls” – are born to Victor, who runs a Chinese restaurant, and his wife Jade, an aspiring realtor.

Eldest Jane, in perfect Asian daughter form, is studying to be a doctor, while Elizabeth, affectionately known as LB, is a fresh communications and photography graduate on a job hunt. Self-righteous Mary is easily overshadowed by her louder younger sisters, the whiny Kitty and model wannabe Lydia.

Enter the Richie Riches who set the plot in action. Brendan Lee and his good friend Darcy Wong have bought over the crumbling but beloved landmark that is the Greater Chinatown Neighborhood Youth Recreation Center. LB is outraged at the prospect of the centre being gentrified by capitalistic sharks with no idea of its roots in the community, never mind that Jade is ecstatic at the prospect of winning a fat commission for the sale.

The marvel is how well Austen’s themes and structure map neatly into this new setting. The cultural specificities of Georgian society find weirdly easy parallels in New York’s Chinese immigrant community. The Chen sisters are as much constrained by gender expectations as the Bennets, their family equally circumscribed by social rules and expectations.

What Chau brings to this retelling is a lively and loving evocation of both this community and the early 2000s New York setting.

She pins, with observation as acute as Austen’s, the character types and behaviours that ring true to every Asian reader. The neighbourhood overachiever whose “accomplishments bullied every Chinese-American girl between Centre and Clinton”. The passive-aggressive competition between Asian mothers over their children: “There were no greater fighting words than open compliments.”

And Chau has a knack for the perfect description that creates an instant visual snapshot, from “Five girls in stiff cheongsam in a range of jewel tones like a collectible Precious Moments tableau” to the neo-noir construction of “He was a dive in a city brimming with boutiques”.

Her snappy one-liners earn well-deserved giggles and keep one turning the pages in search of the next bon mot.

There are throwaway references that root the story as distinctively in its time period as ballroom dances and tea for Pride And Prejudice. The Hilton sisters are a source of inspiration for flighty Lydia, Darcy wields a Palm Pilot and Myspace offers the official stamp on a relationship status.

But more than comedy, Chau deftly works in sharper commentaries on class and migrant mindsets.

Unlike the Bennets, who can still afford servants, the Chens are closer to the poverty line, with seven people crammed into a tiny apartment. Every major expense in the family comes with “a ritual of hand-wringing, desperate pleas at the family altar, and anxiety”.

LB observes witheringly after a tennis game at a posh country club with Darcy and his snooty aunt Catherine, “they win things because other people don’t have the time or money to play”.

Jade’s grasping ambition, like the much vilified Mrs Bennet’s, is rooted in economic anxiety as well as migrant expectations: “And what burdens those dreams were. Money, success, happiness and Chinese husbands.”

But Chau plays her cards well. This is, after all, a light summer read, not a heavyweight thesis on inequality. She proves to be a dab hand at layering the comedy with social commentary, keeping the pace cracking even for dedicated Janeites who know every plot twist from the original.

Part of the pleasure for Janeites will, in fact, lie in the trainspotting. The second Raymond Wu shows up, “dressed in a pink Lacoste polo with the collar popped, slick designer sunglasses, and rocking a string of puka shells around his neck”, fans will have no trouble in identifying the reprehensible Wickham.

Good Fortune is no mere cookie-cutter copy of Pride And Prejudice, but a satisfying meal unto itself.

If you like this, read: Gill Hornby’s Miss Austen (Arrow Books, paperback, $18.95 from Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3qQ7Nae

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.