Book review: Chickpeas To Cook distils stories of women in Singapore’s racial and religious communities

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

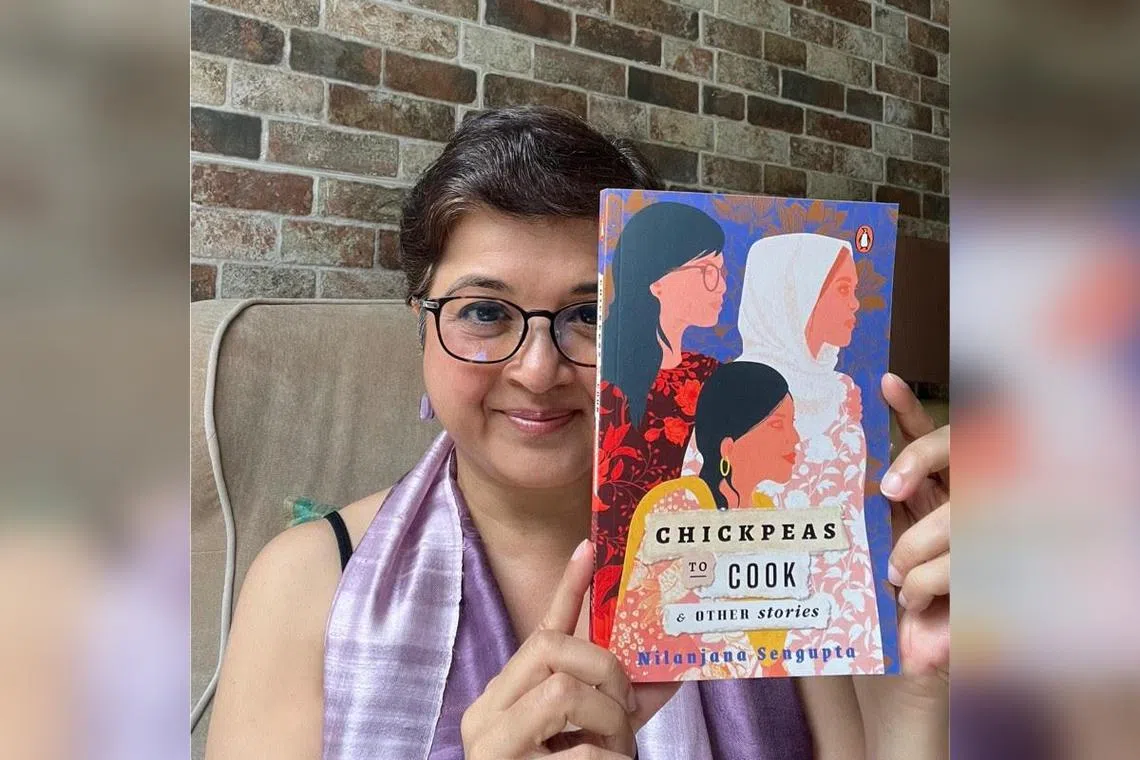

Author Nilanjana Sengupta with her new book, Chickpeas To Cook & Other Stories.

PHOTO: NILANJANA SENGUPTA/LINKEDIN

Follow topic:

Chickpeas To Cook & Other Stories

By Nilanjana Sengupta

Creative Non-fiction/Penguin Random House/Paperback/164 pages/Books Kinokuniya

3 stars

One of the most pervasive constructions of Singaporean identity has been the CMIO model of categorising Singaporeans into Chinese, Malay, Indian or Other.

But many Singaporeans have found this unsatisfactory, searching within the interstices of these categories for who they are.

Nilanjana Sengupta’s new book, Chickpeas To Cook & Other Stories leans into this desire, detailing a world of rich heritage hidden behind this classification created some 100 years ago by British colonial administrators.

It forces readers to pay attention to these terms that are now all too easily reached for by Singaporeans, in the process uncovering a diverse, fractal world of smaller racial and religious groups.

Centring on stories of women from these communities, the accounts here are threaded through with a central tension: How to reconcile deeply held, specific traditions with the cultural erosion that feels inevitable in consolidated metropolises like Singapore.

The compact, 164-page book is broadly organised into eight parts, each of a large organised religion like Islam or Christianity. Within each, Sengupta renders the lived experience of women within smaller sub-religious sects with sensual detail, after brief overviews of each religion.

In the Islam section, she tells the story of Sakinah from the Dawoodi Bohras – a religious denomination within Shia Islam – who struggles with divorcing her cheating husband, an emotional decision made more difficult by strict gender roles for women within her community.

In the Hinduism section, a Nattukottai Chettiar woman, Vishnupriya, confronts the fact that her son is not academically gifted in mathematics, even though their community has traditionally been known for their acuity with numbers.

These stories move quickly and explain the religious lives of these women with a directness that is refreshing and informative.

Yet, as illuminating of the multicultural patina of Singapore as these are, the book cannot help but resort to familiar oversimplifications and generalisations.

In particular, the uneven treatment of different communities featured is not wholly justified.

It is not explained why racial groups like “Eurasians” were lumped under the broader religious category of Christians, or why the Jews and Chinese Taoists were treated with much broader strokes than, say, the Burmese Theravada Buddhists under Buddhism.

Most importantly, however, stories within each section – while told in vivid detail – never really probe the deeper question of why it is important to preserve tradition at all.

Why not surrender to the identities given to people by the state or their present cultural and intellectual milieu? What are the benefits of preserving religious or cultural gender roles?

These are the sort of more pressing questions that are being asked by the majority who may be less automatically predisposed to ethnic nostalgia. Sengupta, by accepting a priori the value of these communities, sometimes unfortunately adopts an exoticising lens.

There may be a radiant aesthetic gloss to her stories, but these sometimes feel too romanticised and just a little out of touch with where Singapore is in this stage of modernity.

If you like this, read: The Indian Trilogy by V.S. Naipaul. Start with An Area Of Darkness: His Discovery Of India (Picador, 2010, $20.49, Books Kinokuniya). It is a semi-autobiographical account of Naipaul’s first visit to India, the land of his forebears.