Book review: An ode to found family and childhood innocence in No Room In Neverland

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

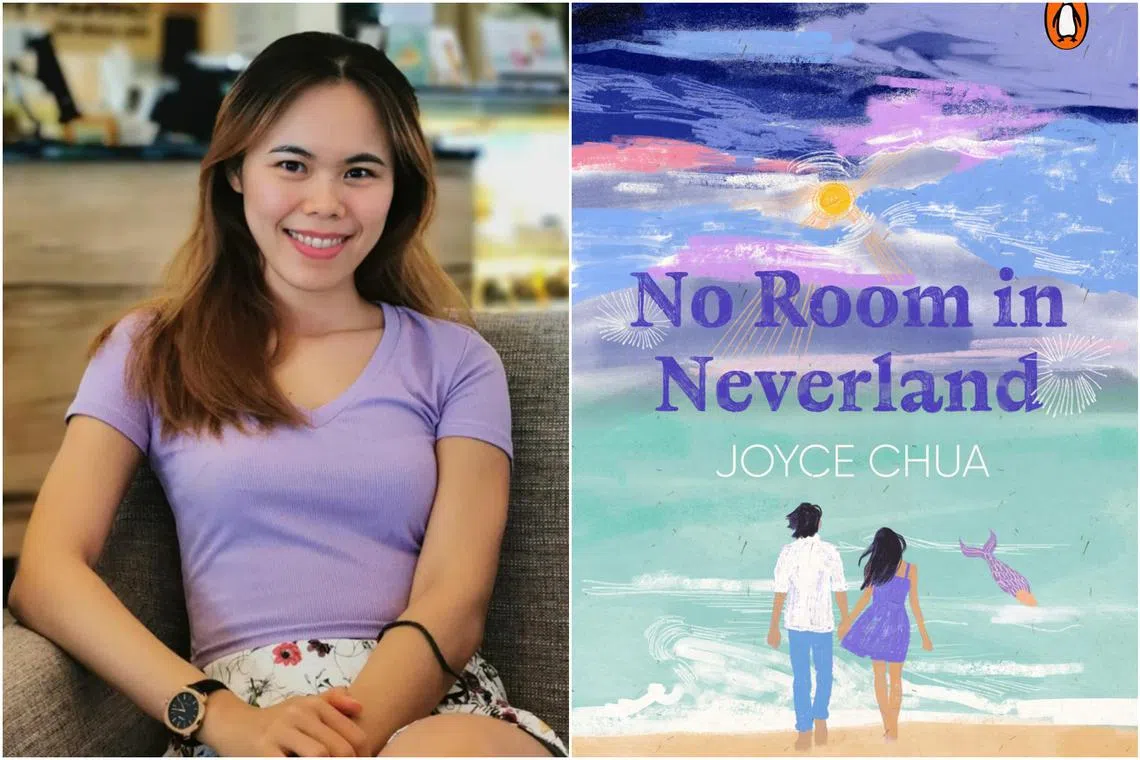

Singaporean author Joyce Chua explores themes of childhood, imagination and found family in her novel No Room In Neverland.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF JOYCE CHUA

Follow topic:

No Room In Neverland

By Joyce Chua amzn.to/493E8KS

Fiction/Penguin Random House SEA/Paperback/256 pages/$17.75/Amazon SG (

3 stars

Neverland and Peter Pan are real. Gemma would know, having been brought there by her mother as a child, though no one around her seems to believe it.

Convinced that Neverland has the answers to the mystery of her mother’s disappearance and her father’s abandonment, Gemma finds that the only person who can help might be Cole, a boy she does not remember but who exudes all the magic of Neverland.

Told in chapters that alternate between Gemma and Cole, their connections to Neverland and each other are slowly revealed as their search for the truth forces them to confront more pain than either could have imagined.

In the acknowledgements, Singaporean author Joyce Chua calls this “the book of my heart”, a reflection of herself in the “escapism, loss of childhood innocence, a dark Peter Pan retelling, a girl’s stubborn optimism and a boy’s cynicism all in one”. The words ring true to the story.

Found family, more than anything else, is the novel’s greatest strength.

Brought up by her foster parents Boon and Jo, owners of the Wild Ride amusement park where she was abandoned, Gemma’s insistence on looking for her birth parents often raises the question of whom she truly considers family and whether she can let go of the past.

Her best friend Thomas acts like an elder brother figure, mediating family matters and stepping in as the voice of reason when Gemma becomes too emotional.

Obsessed with finding her father and understanding what happened to her mother, Gemma’s brash nature can occasionally be frustrating to readers, yet her hyperfixation is understandable as she searches for answers about her abandonment.

Most chapters end with an account from Gemma’s past as she learns about Neverland and visits it. These fragmented glimpses speak to her fuzzy memory of the years before her eighth birthday and the fateful day she was left by her father in front of a Peter Pan ride.

Chua’s descriptions paint a vividly convincing picture of the land where children never grow up. In contrast, the real world lacks substance stemming from the absence of details and information. Characters and their relationships struggle to feel multidimensional, even for Gemma and Cole, whose personalities are subsumed by their obsessions.

Cole tells Gemma: “You’ve been hiding at the Wild Ride all this while, waiting for your parents to come find you, because then you don’t have to deal with the possibility that they didn’t bother looking for you.”

The final reveal begs further questions, most of which go unanswered.

If you like this, read: Straight On Till Morning by Liz Braswell (Disney Books, 2019, $23.53, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3SwqXg7