Book review: Adorah Nworah’s House Woman an unsatisfying thriller

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Adorah Nworah's House Woman follows a Nigerian woman forced into a mysterious arranged marriage.

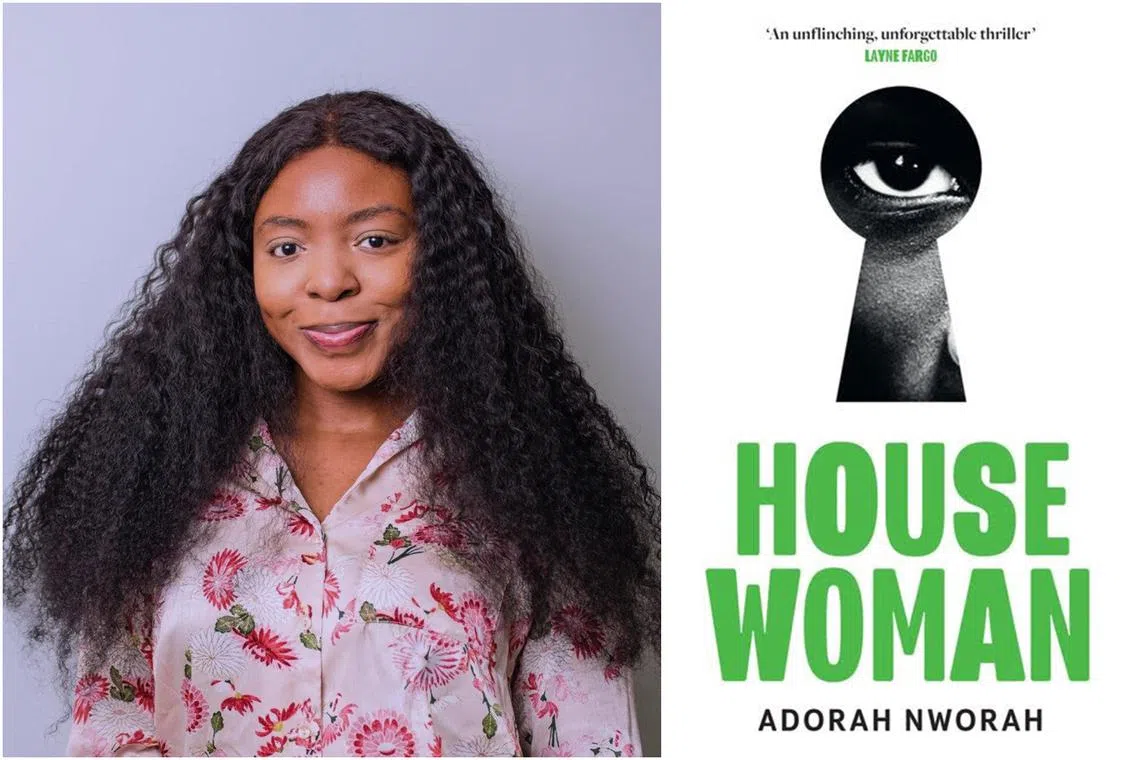

PHOTOS: ADORAH NWORAH, TIMES DISTRIBUTION

Follow topic:

House Woman

By Adorah Nworah

Fiction/The Borough Press/Paperback/288 pages/$23.92/Amazon ( amzn.to/3Y7QYnl

Young dancer Ikemefuna travels from her home in Lagos, Nigeria, to Texas in the United States in search of the American dream.

She is hosted by her parents’ former neighbours from Lagos, Eke and Agbala, in their house in the wealthy Houston suburb of Sugar Land for what is meant to be a short stay. The story that unfolds, however, is far from sweet.

An arranged marriage decided 25 years ago means Ikemefuna is destined to marry Eke and Agbala’s son, Nna, except she is unaware of this agreement. She is confined to Sugar Land, stripped of her freedom, to fulfil the role of obedient wife and mother of Nna’s future child.

This disquieting and violent story may have had promise, but winds up as an unsatisfying thriller.

Adorah Nworah’s vivid writing style effectively disorientates the reader with her claustrophobic setting of airless rooms with pungent smells, illuminated only by artificial lights. The atmosphere is stifling and brims with potential for suspense, but this potential is only intermittently realised.

The mysterious terms of the marriage agreement and Nna’s uncanny resemblance to Ikemefuna’s mother successfully keep the reader engaged. However, the author skips timelines and switches between characters’ perspectives, an unnecessarily confusing choice that leaves readers scrambling to piece together events.

Most of the thrills are derived from the detailed descriptions of domestic abuse. Every main character is either a perpetrator, a victim, or both, creating chapter after chapter of violent episodes that seem inconsequential to the larger mystery of the arranged marriage.

Ikemefuna strangles and injures Agbala within the first few chapters due to a mysterious mental blackout, which puts her in a violent trance upon the slightest of provocations – a condition that is barely explained. This violent episode among many has little significance other than to deepen the reader’s impression of a hostile relationship.

Other episodes of violence seem similarly inconsequential to plot and character development. When Agbala strikes Ikemefuna with the heel of a shoe, when Nna throws brutal punches at Ikemefuna, or when Ikemefuna throws a vase at Agbala – leaving shards in Agbala’s bleeding neck, but it is possibly miraculously healed without medical help as she survives, and it is simply never brought up again.

While the senselessness of the violence may be the point, there is no final catharsis for the reader.

House Woman is built upon themes of domestic violence and the restrictiveness of gendered roles. It shines a harsh and unforgiving light on the reality of violent households and intersectional oppression, particularly for black women.

However, its outlook is intensely bleak. Ikemefuna’s short-sighted escape plans have no hope of success as every attempt quickly leads to a dead end. Every cry for help is left unanswered. What could have been important social commentary becomes a painful, dreary read. Some offer of hope might have given House Woman heft.

If you like this, read: My Sister, The Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite (Atlantic Books, 2019, $18.95, Amazon, go to amzn.to/3Ozz3m8