Book review: A Singaporean vigilante in Myle Yan Tay’s dark debut novel catskull

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

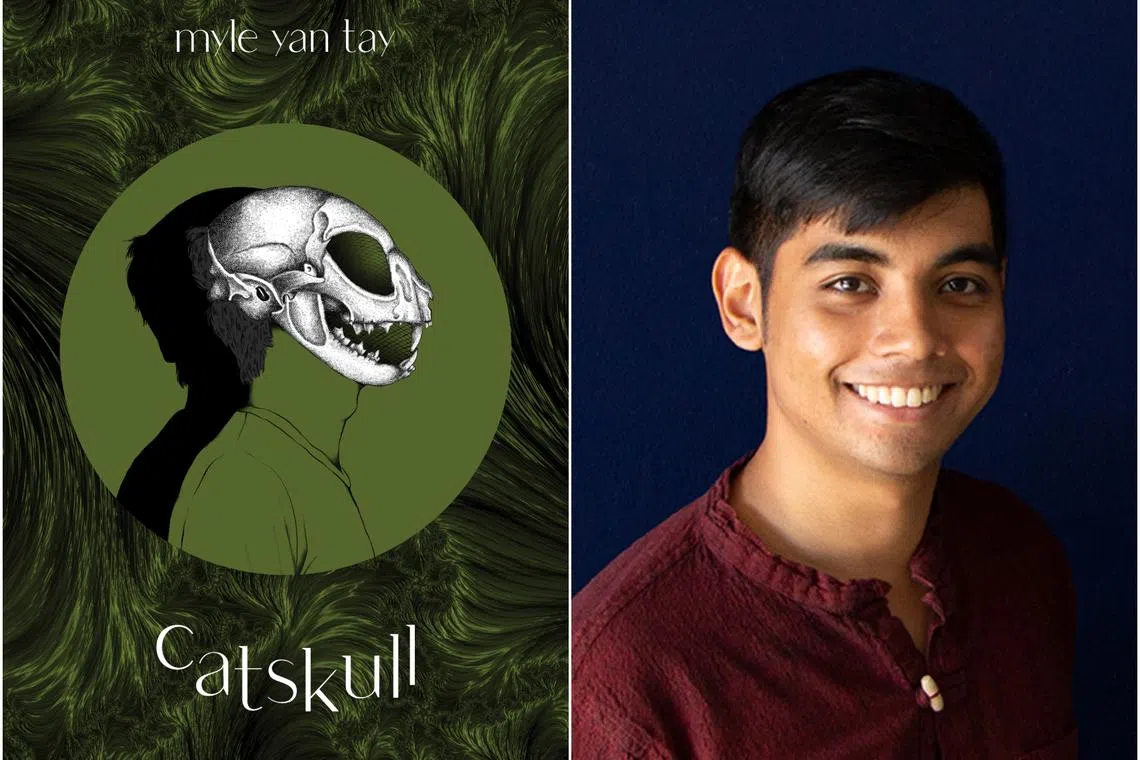

Writer Myle Yan Tay is one of the most promising multi-hyphenates to emerge in Singapore's arts scene.

PHOTOS: ETHOS BOOKS

Olivia Ho

Follow topic:

Catskull

By Myle Yan Tay str.sg/iwLs

Fiction/Ethos Books/Paperback/472 pages/$25.92 before GST/

4 out of 5

“There are two Singapores,” observes Ram, the protagonist of Singaporean author Myle Yan Tay’s debut novel catskull.

There is a Singapore of surfaces, a good, clean garden city. And then there is another Singapore, the one he roams at night on his bicycle: a city of exclusions and sudden violence, of cracks, bruises and screams in the night.

Ram thinks: “When I ride my bike, I am a bullet shot at the city’s heart. I am the knife slashing its veins open, pouring its blood onto the streets.”

Tay is one of the most promising multi-hyphenates emerging in the Singapore arts scene.

The actor-playwright-writer has already published the comics Through The Longkang and Putu Piring (2021), and earlier in 2023 premiered his play, Brown Boys Don’t Tell Jokes, with Checkpoint Theatre to critical acclaim.

His ambitious debut novel further attests to that promise.

It is a dark, unflinching look at what it would mean to be a vigilante in Singapore, transmuting teenage angst into a simmering consideration of toxic masculinity and taboo topics such as racism.

Ram, a junior college student, expects to fail his A levels. His classmates lob racial microaggressions at him regularly. His parents are troubled by him, while his brother Logan, a hyper-masculine national serviceman, mocks him relentlessly.

He is haunted by the death of his Uncle Arun, a family friend and once celebrated lawyer who was disgraced, disbarred and killed in a drink-driving accident where the driver was never caught.

Ram’s only friend is Kass, an intelligent, taciturn fellow outsider he has known since childhood. Together, they watch videos of people dying in online forums or explore an abandoned house, where they find the rotting body of a cat.

When Ram realises Kass’ father is abusing her, however, he decides to take things into his hands.

Soon, he becomes a masked vigilante dubbed the Daitya (Bengali for demon), tackling injustices people post about online.

Though his intentions are good, the violence he wreaks proves addictive. When he puts on the mask, it is the only time he “can see past tomorrow”.

Tay’s influences are clear. Ram watches the cyberpunk anime Akira (1988) and emulates its vigilante bikers in his rides through night-time Singapore.

There are also echoes of the anti-hero Rorschach from the seminal graphic novel Watchmen (1986 to 1987), who fantasises about the evildoers of his city drowning in their “accumulated filth”.

They will look up at him and cry, “Save us”, and he will look down and whisper: “No.”

Yet, Tay succeeds in grounding all this in a Singapore context. He has an unerring ear for the diction of the Singaporean teenager, reminiscent of his fellow Checkpoint Theatre playwright Faith Ng, who similarly conjured a richly detailed school environment in her play Normal (2015).

Though superhero tales tend towards the fantastic, catskull never strays too far from the grit of reality.

Events in the novel, including a case where a Singaporean student beats up migrant workers “for practice”, are drawn from real-life headlines.

The novel, despite its lean, stark prose, rambles on longer than it should and indulges at its end in some formal experimentation that does not quite hit home.

But Tay finely threads the needle of examining how vigilante violence might arise without condoning it. This is a nuanced psychological portrait where nothing is black and white.

If you like this, read: The Dogs by O Thiam Chin (Penguin Random House South-east Asia, 2020, $28.97, Amazon, go to amzn.to/3K1N3CD