‘Art has given me longevity’: Lim Tze Peng, 103, ebullient about National Gallery solo exhibition

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Artist Lim Tze Peng at his house and studio in Telok Kurau ahead of his first solo exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

SINGAPORE – At 103, Singaporean artist Lim Tze Peng has distilled his daily life to three essentials. He eats, he sleeps and, without fail, he picks up his brush to paint.

“Art has given me longevity,” says the Cultural Medallion recipient, whose booming voice echoes through his three-storey home and studio in Telok Kurau.

“Making art every day is like exercising daily – my arms go up and down, left and right. Because of art, I am rarely ill. Whenever I feel a little sick, I’ll just go bask in art.

“There’s not a single day that I do not paint or write calligraphy,” declares Lim, fresh from an afternoon nap, when he appears in his studio with ink stains on his brown pants.

Throughout the 40-minute interview with The Straits Times, he is excitable and ebullient about the fact that his first major institutional show locally since 2003 opens on Oct 25.

Becoming Lim Tze Peng, his first solo exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore, is a small but substantial exhibition of the artist’s works from 1946 to 2023. It begins with his signature Singapore scenes and quickly broadens its ambit to reveal different facets of a man who can be said to have lived a myriad of long lives, in and out of art.

Born in 1921 in a kampung in Pasir Ris, Lim recalls a childhood of poverty, when he manually extracted oil from more than a hundred coconuts every day to sell.

Then, at school, his hands turned to Chinese ink, and his precocious talent was spotted by some of his first teachers – Wong Jai Ling, Yeh Chi Wei and Liu Kang, among others.

Lim recounts in Mandarin: “After class, I would run to the Singapore River to paint the boats. My teachers would close their doors when they were painting, but I would still try to peek in from the outside and watch.”

“Whenever I am near a painting, I get very excited and serious,” he says with a chuckle.

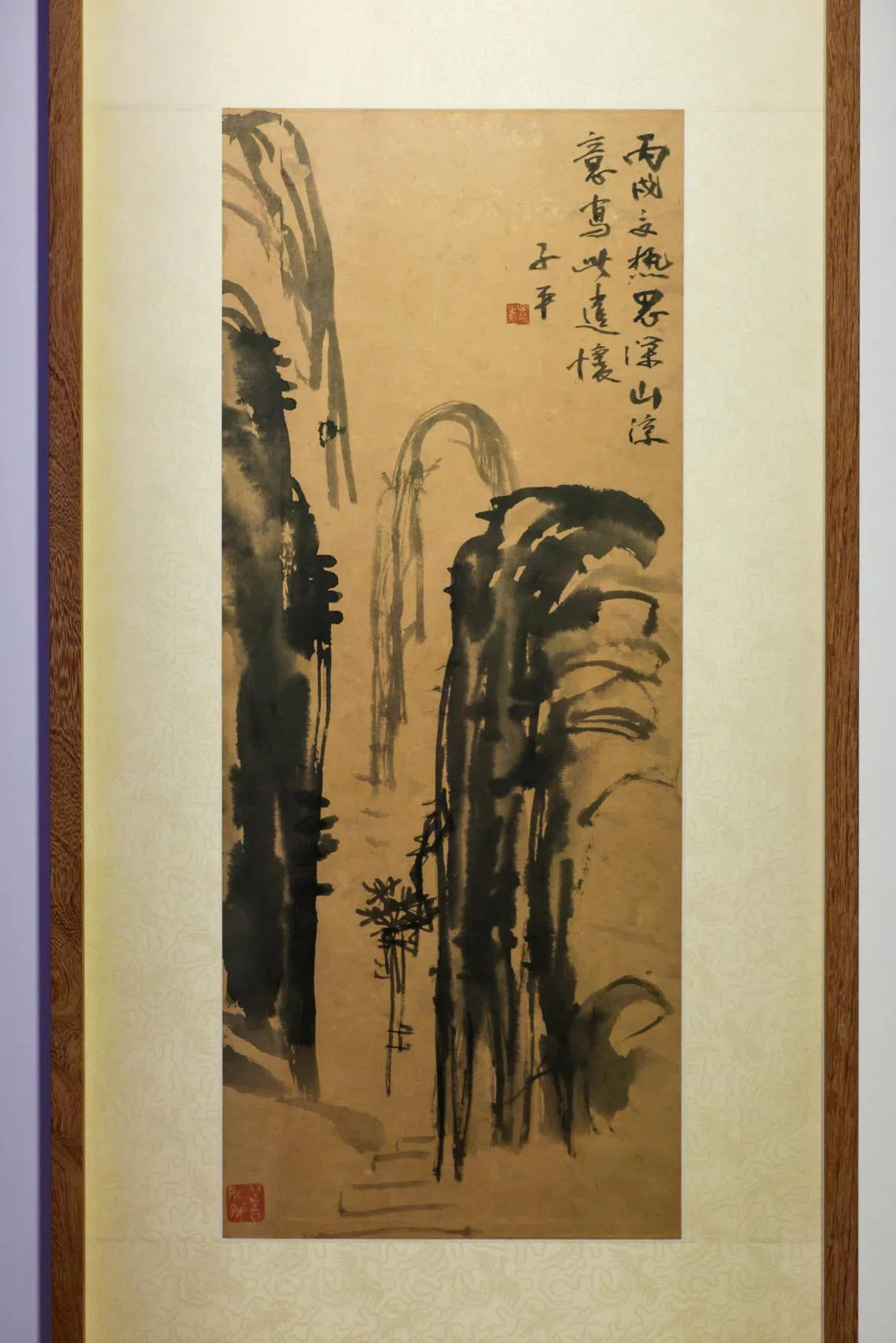

A 1946 ink painting, titled Coolness In The Depths Of The Mountains, is Lim’s earliest-known ink work and shows a skilled if typical mountain scene. Its muted presence in the gallery only serves to accentuate how radically the artist had departed from tradition to forge his own artistic language over the decades.

Coolness In The Depths Of The Mountains (1946) is the oldest-known ink work by Lim Tze Peng on display.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

The show’s first section – From Dapo To Xiaopo (From Big Quay To Little Quay) – contains the recognisable Singapore scenes that Lim largely painted en plein air, or outdoors. His Chinese ink works are juxtaposed with the lesser-shown oil on canvas works, giving viewers a window into the different materials he worked with.

Here, bygone scenes – of hawkers, repair shops, wayang stages and mosques – recall a vanished Singapore that Lim loved to paint. The organic arrangement of the old alleys and streets, he says, was what made such scenes so intrinsically drawable.

“During founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s time, when he ordered the clean-up of the Singapore River, and when old buildings were demolished, I felt a real surge of anxiety,” Lim recalls. “Every morning, I would drive into the city before 8am – to avoid the congestion surcharge – and draw at least two paintings a day, until the afternoon.”

The exhibition opens with familiar scenes from Lim Tze Peng’s oeuvre, such as Singapore street hawker scenes.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

“To make a good painting, the most important thing is to sketch from life and nature,” he insists.

His limited mobility means he cannot go outdoors to paint any more. But even in his humble studio, he paints what he can see from his vantage point – even if these are the vases and pots gathered at the top of his cabinet.

Otherwise, he paints from memory – going over the same scenes and bringing fresh eyes to old subjects.

An intriguing middle section titled The World Outside ventures beyond Singapore – and beyond what casual art lovers know of Lim.

As a core founding member of Ten Men Art Group, Lim had made five art expeditions across South-east Asia and painted scenes from Bali to Brunei to Sumatra.

These trips had provided reprieve from his role as principal of the now-defunct Sin Min School, a position which he held from 1950 to 1981. There, he taught first in Hokkien, and then in Mandarin. He also taught art classes.

But less well known are his European travels.

In 2000, he did a residency in Paris organised by the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, during which he painted urban as well as pastoral landscapes. This included paintings of a mediaeval village in the Alpes-Maritimes department, south-east of France – the same places that inspired Western masters such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

Shophouses (2000) and Dining Out At A Cafeteria (2000) both take urban Paris as their subject matter. But when the exhibition’s curator Jennifer K.Y. Lam casually asked the art handlers to identify the scene, she was intrigued that people perceived them as Singapore scenes – which led her to ponder about Lim’s relationship to home.

She says: “Could he have been missing home when he was spending the two to three months in Paris? I don’t have a hard answer, but I think it’s really nice to think of it that way, isn’t it?”

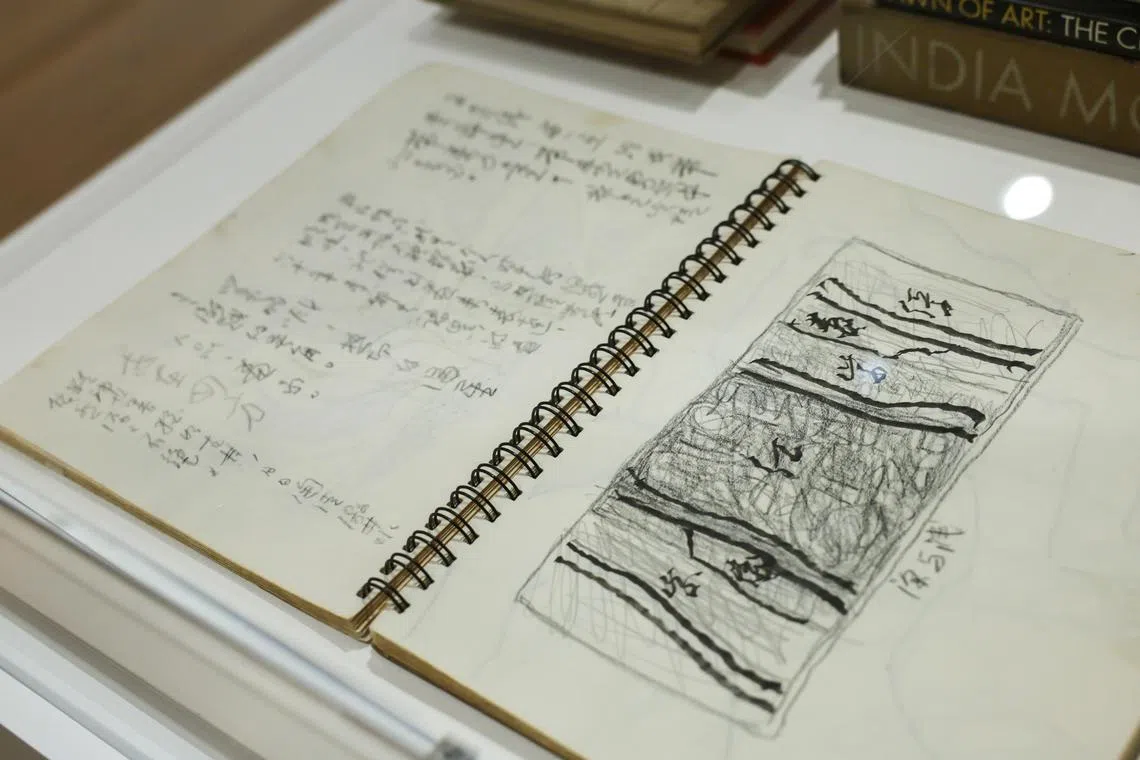

Ms Lam, who has been visiting Lim’s family weekly since more than a year ago, has also curated a display of never-before-seen materials from his home. These include reference books, scrapbooks and sketchbooks – objects that lend insight and credence to his oral history, which art historians primarily rely on today.

In one sketchbook on display, Lim lists six qualities of a good painting, including enigmatic entries like “quality of ethnicity, culture and nationality: lines” alongside sketches.

Ms Lam, a curator at the National Gallery Singapore who is in her 30s, says: “He has created his own visual dictionary.”

Lim Tze Peng’s handwritten notes in a sketchbook are on display at his solo exhibition Becoming Lim Tze Peng at the National Gallery Singapore.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

These notes are best considered in the light of the exhibition’s third and final section, On My Own Grounds, which engages with Lim’s more experimental and abstract works.

With the invention of his own calligraphic idiom – hutuzi (Chinese for “muddled writing”) – in the mid-2000s, Lim had his greatest artistic breakthrough.

“I’ve always thought my calligraphy is better than my painting,” says Lim. But in hutuzi, there is no need to choose – calligraphic characters approach the language of painting such that there is no meaningful distinction between the two. In bold, expressive lines, the paintings dance and find their own music.

Curator of Becoming Lim Tze Peng, Ms Jennifer K.Y. Lam, at a media preview tour of the exhibition on Oct 23.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Lim estimates he has made more than 20,000 works of art over his lifetime. They are highly sought after by private collectors and can go for upwards of $200,000 at auction, but Lim – who says he is not in it for the money – is indifferent.

“As for my best works, I’m not even willing to sell them to collectors who quote a high price. I’m keeping them in the hope that the nation will collect them – even if they are acquired at half-price,” he says, hoping that his work can be on public display for generations to come.

There are currently 299 of his works – dated from 1953 to 2008 – in the national collection.

While he has a personal stake in ensuring his works enter Singapore’s collection, Lim is also thinking about the country.

“If a nation wants to boost its international standing, of course it has to build good arts and culture. Many countries today do not care about culture, they care only about building good weapons. That can only spell doom for its citizens.”

He adds: “We are a small country. We should have a plan to raise the bar for the arts – which will raise the quality of life and the people’s spirit.”

Asked what his greatest life accomplishment has been, the centenarian says: “When I look at my work and compare it with that of international artists, I think I’m as up to the mark as them. I’m not boasting, but my works have reached an international standard. I’m very happy and satisfied with my output.”

Lim has put on solo exhibitions internationally, including at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. In October 2023, he made his exhibition debut in the West at Saatchi Gallery in London, with an exhibition titled From Lion City To Thames.

Centenarian artist Lim Tze Peng is proud that his works have reached an international standard.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Lim’s son, Mr Lim Su Kok, 79, the eldest of six siblings, describes his father as completely enraptured by his artmaking even at his age. He says: “You can’t call this his late period – because he’s a non-stop artist.”

The elder Lim lives with his wife, Madam Soh Siew Lay, 98, and told ST in 2010: “She always said, ‘Art is your first wife, I’m just your second wife.’”

He adds: “There is an ancient saying which goes, ‘Life is short, art is forever.’ I think they’ve got it right. A human life can last a mere hundred years,” – and he says this without any irony – “but art can survive for thousands of years.”

“I don’t think about my age,” he says with a smile. “I just think about how to make good art. Nothing can hold a candle to art.”

Becoming Lim Tze Peng: His artistic odyssey in five works

1. Singapore River II (circa 1976) and Singapore River (Coleman Bridge) (1979)

Detail of Singapore River (Coleman Bridge) (1979) by Lim Tze Peng.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Better known as an innovator of Chinese ink, Lim also brought his sensibility in ink to his lesser-known oil paintings.

Two panoramic Singapore River scenes – done three years apart and placed side by side – offer a chance to re-evaluate his legacy in different mediums.

“He slowly tries to inject certain non-oil-painting techniques into his oil work,” says Ms Lam, who points out the slender and sharp brush work on some of the trees in Singapore River II (circa 1976) that is not typical of oil painting.

While Lim’s Chinese ink achievements are more celebrated and easily appreciated, the oil work was once selected by Ms Constance Sheares – then curator of art at the National Museum Art Gallery – for its inaugural exhibition in 1976.

Detail of Singapore River II (circa 1976) by Lim Tze Peng.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

2. Shophouses (2000)

Shophouses (2000) by Lim Tze Peng.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

These shophouses are not the two- to three-storey-high narrow architectural styles that are seen in Singapore and across South-east Asia, but one could be forgiven for thinking so.

In fact, Ms Lam points out that the green facade is probably inspired by the Shakespeare And Company bookstore by the River Seine in Paris. What might this say about Lim’s attitude towards the vanishing shophouses of Singapore?

Lim, who paints en plein air, said in an interview cited in the exhibition catalogue that he had “almost covered the entire France” during his residency in Paris. Dotted across this second room are some of the most intriguing output of his European flanerie.

3. Inroads (No. 1) (2006)

Inroads (No. 1) (2006) by Lim Tze Peng.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Measuring almost 5m wide, this ink and colour painting is the largest work of Lim’s on display. Resembling calligraphic script, the abstract work sees him harnessing the energy of the line to create a force of nature.

While the title is introspective, this is also a work which brought him out into the world and the acclaim of his counterparts in China.

The work travelled to the National Art Museum of China in Beijing and the Liu Haisu Art Museum in Shanghai in 2009.

4. Lim Tze Peng At Work In His Studio, Singapore, 2013 (2024)

The video work Lim Tze Peng At Work In His Studio, Singapore, 2013 (2024) plays in the background.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Commissioned by the National Gallery Singapore in 2013, this video recording of the artist completing a calligraphic work from start to end has never been seen before.

In slightly under 12 minutes, he writes a stanza from the poem Three Poems On Early Autumn No. 1 by Tang Dynasty poet Xu Hun. After failed attempts to pursue a career in politics, Xu considered retiring in seclusion, but was unwilling to spend the rest of his life by the river.

Recorded in Lim’s home studio, the meditative video allows the viewer to get an intimate glimpse into the master’s calligraphic methods, as he works on a piece of paper larger than himself.

5. Regardless Of Right Or Wrong, Success Or Failure, It All Turns Into Emptiness; Only The Lush Mountains Remain, And The Red Sunset Persists (2023)

Regardless Of Right Or Wrong, Success Or Failure, It All Turns Into Emptiness; Only The Lush Mountains Remain, And The Red Sunset Persists (2023) by Lim Tze Peng.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Made between November and December 2023, this is the newest work of Lim’s on display.

The title, which reflects on themes of ephemerality, is derived from the poem Immortals By The River by Ming Dynasty poet Yang Shen.

In contorted glyphs that look like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, Lim invokes the vertical script of Chinese calligraphy. But in the absence of any identifiable characters, he seems to have reached a purer stage of abstraction in this work.

This latest work reflects his restless journey to make art and to break through to the next artistic frontier, even as he turns 103.

Book it/Becoming Lim Tze Peng

Where: National Gallery Singapore, Level 4 City Hall Wing, 1 St Andrew’s Road

When: Oct 25 to March 23, 2025, 10am to 7pm daily

Admission: Free for Singaporeans and permanent residents, from $15 for non-residents

Info: