Actor Matthew McConaughey distils his philosophy into a kids’ book

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

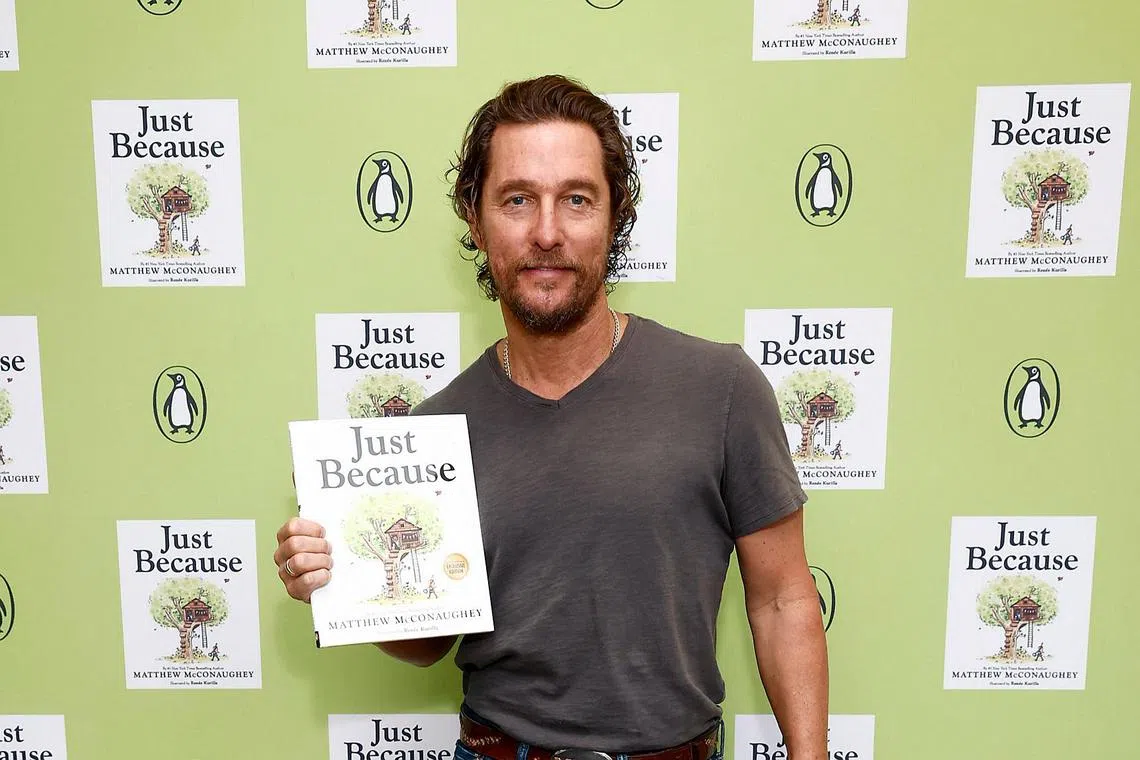

Matthew McConaughey celebrating the release of his book, Just Because, on Sept 16 in Los Angeles.

PHOTO: AFP

Follow topic:

NEW YORK – Matthew McConaughey is in author mode. In 2020, he wrote a best-selling memoir, Greenlights, a walkabout in his mind made up of a lifetime’s worth of musings.

Now, the American actor, 53, who lives with his wife, Brazilian Camila Alves McConaughey, 40, and their three children in Austin, Texas, has distilled his philosophy – his persona, even – into a children’s book.

Just Because, published in September and illustrated with playful subtlety by Renee Kurilla, is composed of inspirational lessons in the form of couplets. “Just because you can pull it off, doesn’t mean that you should do it,” reads one. “Just because you failed, doesn’t mean that you blew it.”

Fans of Greenlights – or, indeed, of McConaughey’s long career – will not be surprised by the book’s occasionally gnomic tone and approachable style, or by the philosophical meditations interspersed with moments of self-deprecation: “Just because you wrote it, doesn’t mean that I read it.”

In a way, Just Because feels like a manifesto. “To my kids, your kids and the kid in all of us,” reads the dedication on the last page. “We’re all as young as we’re ever gonna be, so let’s just keep learning.”

Did anyone tell you not to do this?

No. I have had people saying for a while, friends of mine, to write a children’s book. We will be sitting around as parents, talking, and sometimes people will go, “Hey, that’s a great way of saying what you just said. I’m going to use that with my own kids. I like the way that you threw that off, how you informalised that very formal-feeling lesson.”

How did you arrive at this structure?

I had a little ditty in my head. I had been listening to American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited (1965). I woke up, and I was like, I got a rhythm going here. I got something kind of cool.

I wanted to get some more sleep, but I was like, no, get up and start writing. Next thing, I am up for hours and I have 120 couplets. Got some more sleep. Woke up four hours later, and I looked at it. A bunch of it is cool, touch on what my kids are going through, and stuff that I am talking to them about.

So, wait, should we imagine this in your voice, or a Dylan voice?

I imagine it in my voice, but to a Dylan riff. I mean, Dylan was the original rapper.

His rhythm was big for me in Greenlights: slinging it from the hip, yet still structured. He goes out and about and brings stories back home in a roundabout way. That is a lot of the way that I think.

Is that typical of your writing process?

I write daily, so I write anything that inspires me. I have never got up and said, “I’m going to go sit down and write.”

I write freestyle and, at the end of each month, I will look back and find that I had themes, different associations to a subject. Then I’ll try and log those together, throw them in there, and see, how do I connect those? What’s the through line?

The hardest part is getting the first line. As soon as it comes, the rest just goes. It just comes out. It is getting the note, the metre, the tone, the jive, the delivery; how much swing does it have?

I read it to my three-year-old, and now I can talk and think only in transactional couplets.

I find that either humour or music, in things that could feel so weighty, put rhyme to the reason. Now, my Monday morning feels like a Saturday night. Now, the broccoli tastes good.

When we are going through something frustrating or confusing, we think the world’s revolving around us, that we are the only ones who feel that way. Then you get a little riff and you put a couplet to it, and you’re like, oh, this is a human condition. People have felt this way for all time.

You mentioned some of the book came out of conversations you have been having with your kids, who are now 15, 13 and 10.

Indirectly, they probably had a lot of input. Since I have been a father, the way I think and the way I try to figure out the world is seen through the lens of their lives.

Do they like it?

They dig it. My daughter’s very visual. My eldest son gets it and thinks it’s cool. My youngest is still letting me know what he likes. He sits back a little more and lets me know later.

My mum digs it. She was a teacher. She’s like, “Yeah, this is all the stuff I taught you.”

But why a children’s book?

Paradox is a tough thing for a mind to grasp, and not just for young minds.

It is almost like we can go, hey, I have my amnesty card here, comedy. So, I cannot really be blamed or victimised or chastised for it because, hey, it was a ditty. And I think it is a fun way of communicating.

So, a children’s book is an easier place to express a certain kind of nuance.

No doubt. No doubt. That is why it was freeing for me to go there. I am writing like an eight-year-old because what an innocent, fun place to go to. What a place of forgiveness and freedom and creativity. NYTIMES