‘A lot of nonsense being spouted’: Nobel laureate Venki Ramakrishnan on the anti-ageing industry

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

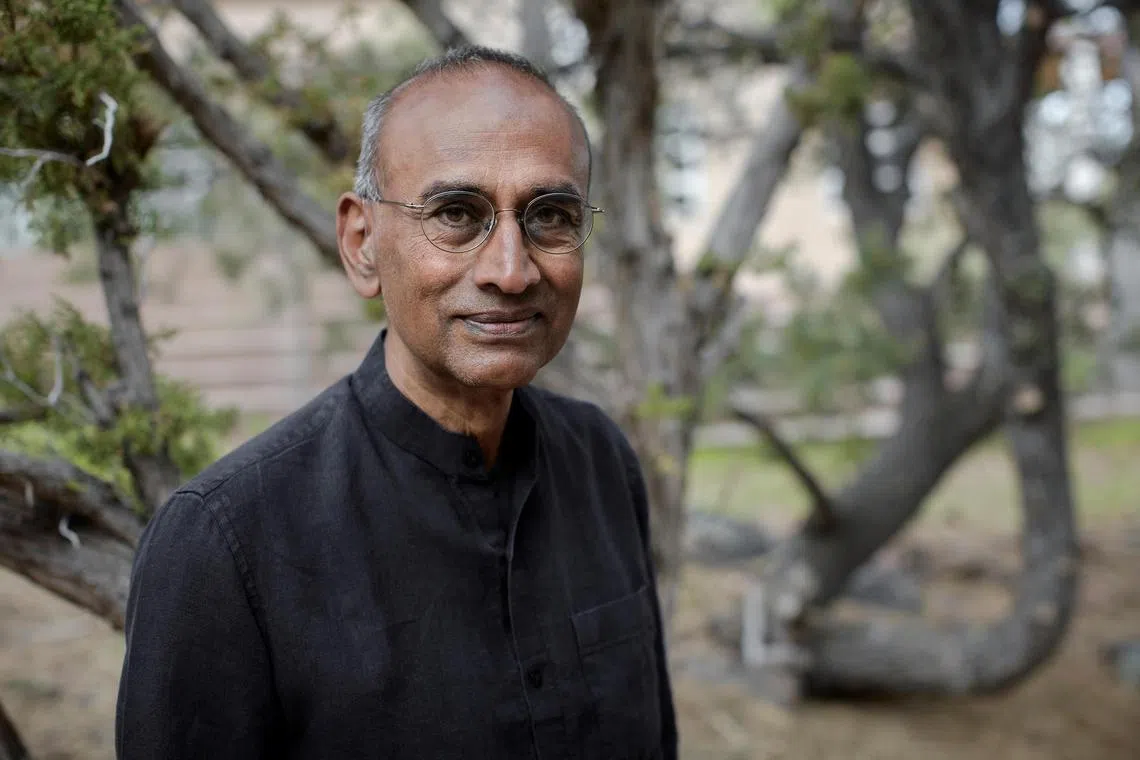

In his new book, British-American scientist Venki Ramakrishnan is merciless in his debunking of such “crackpot” promises like cryogenics.

PHOTO: KATE JOYCE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Midway through the interview with 2009 Nobel Prize winner Venki Ramakrishnan, the structural biologist unexpectedly initiates a reference to Singapore.

“It strikes me as a slightly impatient country,” he says. “It wants to invest in research and then it wants returns right away. Science doesn’t always work that way. You need patience and a long-term view.”

This exhortation for time for the scientific community to do its best work has led the 72-year-old British-American scientist to write his new book, Why We Die: The New Science Of Ageing And The Quest For Immortality.

The former president of the Royal Society’s expert voice is an “objective look” at the hype surrounding newfangled attempts to stave off death.

In recent years, these have included anything from American venture capitalist Bryan Johnson’s transfusion of his 17-year-old son’s blood plasma to revelations that tech investor Peter Thiel has signed up to be cryogenically preserved.

The longevity industry, exploding over the last 40 to 50 years, is today a $40 billion industry and irresistible catnip for speculative investors and dubious start-ups.

“There’s quite a lot of serious ageing research going on,” Dr Ramakrishnan says. “But there’s also a lot of nonsense being spouted.”

In Why We Die, Dr Ramakrishnan is merciless in his debunking of such “crackpot” promises like cryogenics. It is only in recent years that scientists have successfully preserved a mouse brain, he says, infusing it with embalming fluid while the mouse’s heart is still beating and so killing it without any possibility of re-stimulation.

But other avenues such as caloric restriction and targeting senescent cells for destruction are more plausible.

Surprisingly, Mr Johnson’s obsession with blood is not entirely off-tangent. There is some evidence that young blood can activate stem cells and repair damage sustained over time, though much more research has to be done before such treatments can be meaningful.

“There’s a whole field of research that is trying to identify factors in blood that might help with ageing,” says Dr Ramakrishnan, whose life work focuses on protein synthesis. “You’d have to identify factors, figure out what they do, and then see if you can provide them safely and still have the same effect.

“It’s a long-term problem. People are not willing to wait for the science and the clinical trials to be done to establish efficacy. They are jumping the gun.”

Though this speaks to a very human fear of dying – the author confesses he is not immune – it is not a harmless impulse. Cell reprogramming, another promising area of research, comes with the risk of cancer.

Why We Die: The New Science Of Ageing And The Quest For Immortality is available at major bookstores and Amazon SG for $28.68.

PHOTO: HODDER PRESS

Dr Ramakrishnan compares these advances with technologies like artificial intelligence, the implications of which are not always well-thought-out and which did not work for a long time until, suddenly, it catapulted forward at an unimaginable pace.

Though he believes reducing morbidity is the more realistic aim, a last chapter also entreats policymakers to consider the societal impacts of a significantly longer lifespan for humans, if somehow advances allow humanity to bust its current 120-year-old age cap.

Among the problems he raises: entrenched inequality and older people staying on in positions of power beyond what is beneficial for society.

“In many fields, including science, but also in many other creative enterprises, the most creative work was done by people when they were relatively young. Scientists like me continue to do good work, but that’s because we’re surrounded by young people who are really bright and creative,” he says.

He labels it an issue of generational fairness. “You’re taking resources away from younger people. You don’t have to push older people out, but maybe they can adapt to roles that are more appropriate.

“If you are doing hard, manual labour, it’s also not fair to ask people to keep doing it unless we can keep people physically strong and healthy,” he adds, referring to resistance that has already erupted such as the gilet jaunes (yellow vests) protests in France in 2018.

Overall, ageing research continues to take up only a few per cent of global research budget. Dr Ramakrishnan refrains from commenting on whether this is the correct amount except to say it is important to keep basic research going.

Many advances in ageing research did not come from ageing research as such but from those who were studying problems that had apparently no connection with gerontology. “You never know where particular research is going to lead in terms of applications,” he says. “That’s always been true in science.”

His advice for a good, long life? The platitudes of eating more fruits and vegetables, sleeping an adequate amount and getting regular exercise apply.

“These three affect major pathways in ageing. That’s probably a good place to start,” he says, before adding: “The industry will start coming up with other alternatives. Meanwhile, don’t forget to live.”

Why We Die: The New Science Of Ageing And The Quest For Immortality is available at major bookstores and Amazon SG for $28.68 (

amzn.to/3R21pGD

).

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.