Architect Frank Gehry’s essential, stunning projects

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Celebrated American architect Frank Gehry left behind playful, polarising buildings across the globe.

PHOTOS: PHILIP CHEUNG/NYTIMES, DENIS DOYLE/NYTIMES, AFP, REUTERS

The most celebrated architect of his age, a wry, pugnacious, singular genius, Frank Gehry redefined American architecture and became so famous that he was even a character on animated sitcom The Simpsons (1989 to present). He died on Dec 5

In Bilbao, Berlin, New York and, especially, Los Angeles – where the Canada-born Gehry settled and became inseparable from the city – he left behind playful, polarising, materially and technologically stunning buildings.

They emerged from an artistic evolution that tracks the larger arc of American post-war culture. Some of Gehry’s best, less-famous buildings came early – in small, experimental projects with tight budgets – as well as late, in imaginary plans he cooked up for Los Angeles and in designs for concert halls that tapped his love for music. Here is a selection.

Frank Gehry at his architecture studio in Los Angeles, on April 6, 2021.

PHOTO: ERIC CARTER/NYT

Danziger House, Los Angeles (1964 to 1965)

Tucked among the noisy bars along Melrose Avenue, Gehry’s minimalist, two-storey Danziger house and studio, from 1965, put the architect on LA’s architectural map.

Recessed from the avenue, the project offsets a pair of grey stucco cubes, blank facades on the street, enclosing an interior courtyard. Gehry added large windows and skylights, letting sun carve shadows inside the cubes.

Already he is making art of necessity: Exposed conduits and ventilation systems nod to SoHo lofts, and the stucco is the same stuff highway crews in Los Angeles spray on underpasses.

Ron Davis House, Malibu, California (1968 to 1972)

Ron Davis, a Southern California hard-edge abstractionist known for his shaped canvases, commissioned Gehry to design a house and studio in Malibu. Davis’ house would be Gehry’s first building featured in a national magazine.

A trapezoid of distinctly sharp angles, a nod to Davis’ art, the house is built from plywood and corrugated metal, extending Gehry’s experiments with geometries and what he affectionately called “cheapskate” materials. Sold by Davis in 2003, the house burned down in 2018.

Frank and Berta Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, California (1977 to 1992)

An eyesore to stuffy neighbours, now a shrine to architects and architecture buffs, the Santa Monica house that Gehry and his wife, Berta, bought during the 1970s started out as an ordinary, pink, 1920s-era Dutch Colonial bungalow.

It became a glorious petri dish, earning Gehry his first dose of international fame. Various Rube Goldbergian interventions, extensions and other experiments with chain link and raw plywood reinvented domestic architecture for the late 20th century, borrowing inspiration from artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Gordon Matta-Clark.

Vitra Museum and Factory, Weil am Rhein, Germany (completed in 1989)

Gehry’s first completed building in Europe, the museum and warehouse he designed for Vitra, the pioneering Swiss furniture company, represented a creative pivot point.

The design alludes to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim in New York and perhaps Le Corbusier’s chapel in Ronchamp, France. Composed of swooping, swirling, jutting forms, the museum’s sculptural exterior expressed a complex of specific functions inside.

The project came to be associated with Deconstructivism, a new architectural movement whose computer-aided explosions of lines and volumes were custom-made for an emerging universe of photo-based media.

Fred and Ginger, Prague (1992 to 1996)

On a long-vacant site in Prague, bombed during World War II, Gehry conceived a pair of office towers that look like canoodling dancers. Fred and Ginger, as the project became known, mixed comic elements of Hollywood pizzazz with nods to Prague’s traditional 19th-century architecture.

It spoke to a fresh optimism in central Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall – and to architecture’s allusive poetry and power. Fred and Ginger, leaning and swaying, emerge from their staid architectural neighbours on this corner of the Czech capital, just as the city was emerging from the Soviet era.

Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain (1991 to 1997)

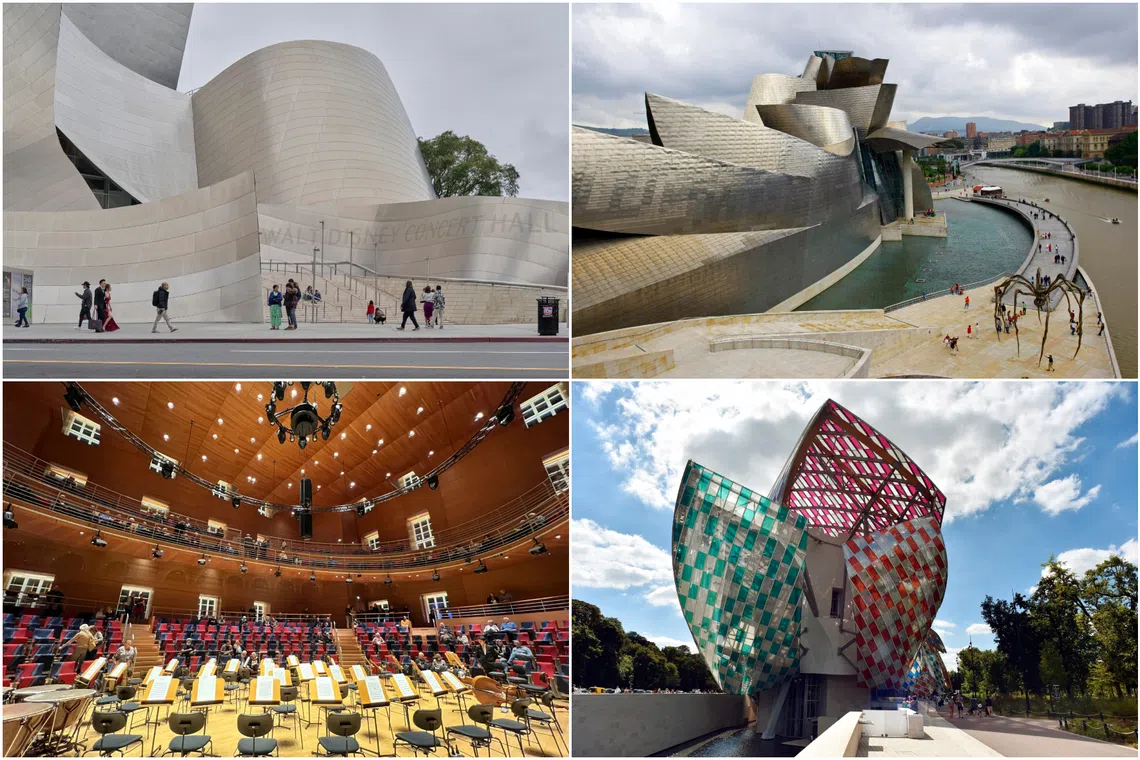

The Guggenheim Bilbao, a fish-shape art museum on the riverfront, defined Frank Gehry and architecture at the turn of the century.

PHOTO: DENIS DOYLE/NYTIMES

Bilbao had already been getting an architectural makeover when Gehry’s game-changing, unforgettable, fish-shape art museum landed on its riverfront. The museum instantly made the former industrial city an alternative to Rome and Paris for highbrow art-and-architecture tourism.

The project provided Gehry with that rarest of clients, who allowed him to test out methods and concepts he had been evolving for decades. Architect Philip Johnson compared the result with Chartres Cathedral in France. It may not last 800 years, but it is the building that will forever define Gehry – and architecture at the turn of the 21st century.

Disney Hall, Los Angeles (1988 to 2003)

The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.

PHOTO: MONICA ALMEIDA/NYTIMES

With its warm, wood-lined interior and acoustics, Disney Hall is, first and foremost, a terrific place to hear music. But it is also a spectacle on the skyline, its riot of shimmering steel panels opening up like the petals of a giant flower under the Southern California sun.

What the Chrysler Building and Eiffel Tower are to New York and Paris, Disney became to downtown Los Angeles. Begun before Bilbao and finished after it, the concert hall helped germinate Gehry’s ideas for the museum and, among his achievements, ranks right up there alongside it.

DZ Bank, Berlin (completed in 2001)

Inside a mixed-use development near Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Gehry inserted a conference space whose fantastical, undulating, totally unexpected shape looks a little like a whale floating in midair.

The building’s dull exterior acts almost like a straight man for Gehry’s playful punchline. It is an architectural tour de force not unlike what architect Norman Foster, to greater symbolic and theatrical effect, did with the inside of Berlin’s Reichstag, a few blocks away.

8 Spruce, New York City (completed in 2011)

8 Spruce Street, Frank Gehry's first skyscraper, rises 76 storeys over Lower Manhattan in New York.

PHOTO: ROBERT DEITCHLER/NYTIMES

Gehry’s first skyscraper, 8 Spruce Street, rises 76 storeys over Lower Manhattan, its facade clad in more than 10,000 differently shaped stainless-steel panels whose arrangement suggests draped fabric.

The tower nods, across a century, towards the Neo-Gothic filigree and reflective terracotta tiling on the nearby Woolworth Building. Pleats in the “fabric” make room for bay windows inside high-end apartments that jut like prows into the skyline.

The building’s metal exterior “breathes” over the course of a day, its metallic skin turning a shade of pink in the early morning sun, umber as the sun sets.

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris (completed in 2014)

An aerial view of the Louis Vuitton Foundation with a temporary work by French artist Daniel Buren at the Bois de Boulogne public park in Paris.

PHOTO: AFP

With the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Gehry swopped steel panels for billowing glass to devise one of his most graceful extravaganzas.

The foundation sits at the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, the Paris park. It takes inspiration from earlier glass buildings in Paris like the Belle Epoque Grand Palais. Its composition can conjure up a sailboat, shards of an iceberg or the facets of a Cubist collage.

As at Bilbao, exhibition rooms mix conventional, rectilinear spaces with highly sculptured ones. “The sterilised model of making art galleries has been misunderstood as neutral,” Gehry said, “when in fact its quasi-perfection is as much a confrontation to the art as anything else.”

Pierre Boulez Saal, Berlin (completed in 2017)

The Pierre Boulez Hall of the Barenboim-Said Akademie in Berlin Mitte.

PHOTO: REUTERS

In his later years, Gehry devoted increasing amounts of time and thought to music, an abiding passion. Boulez Saal, a gem, can put a listener in mind of a cello. Wooden ellipses of tiered seats surround the stage, creating a warm bowl inside an old masonry building.

Dedicated to the great French modernist composer Pierre Boulez, devised in concert with conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim, the 683-seat hall reveals a side of Gehry that is not the fabulist but the intimist – an architect who could create practical and humane spaces that yielded the spotlight and lifted the soul.

Los Angeles River Proposal (unbuilt)

Gehry, a transplanted Canadian, remained, on a deep level, a local architect, tethered to Los Angeles, where he spent his long career.

To the end, his office laboured on diverse projects for the city, which sometimes provided a counterpoint to his more spectacular buildings, including a housing development for formerly homeless veterans and a remaking of a derelict stretch of the Los Angeles River.

That multibillion-dollar river proposal dreamt of a roughly 1.6km-long platform erected over the concretised waterway, adding parkland and other open spaces as well as a cultural centre to serve some of the poorest communities in the city. NYTIMES