All the ways AI did not live up to the hype in 2025 – and what’s next in 2026

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

An AI-generated image (left) of a property listing presented alongside a photograph found on PropertyGuru.

PHOTO: SCREENGRABS FROM PROPERTYGURU

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – In November, The Straits Times contacted real estate listing platform PropertyGuru to ask about the growing trend of AI-generated images

In response, the company told ST that “fully AI-generated photos” were not allowed on the platform. When provided with specific examples where such photos were used without disclosure, the company later added that any virtual staging or edits should be clearly indicated.

“Our team has reached out to the agents involved to take corrective action where needed,” said the company’s spokesperson. The AI-generated images in the examples cited were removed.

However, six weeks later, a search through the platform reveals multiple property listings where AI-generated images are still being used without disclosure – at times in place of any real photography of the living space being advertised.

This instance is emblematic of many implementations of artificial intelligence in Singapore in 2025: public controversy that fizzles out into a collective shrug.

The year AI became unavoidable

If 2022 was the year that first unleashed AI mania on the world, after the public release of generative AI tool ChatGPT, 2025 was the year that AI became unavoidable.

Singapore social media is awash with examples of netizens pointing out strange and unnatural AI-generated imagery used in marketing campaigns. AI-generated images are no longer an uncommon sight on posters and signs in heartland neighbourhoods.

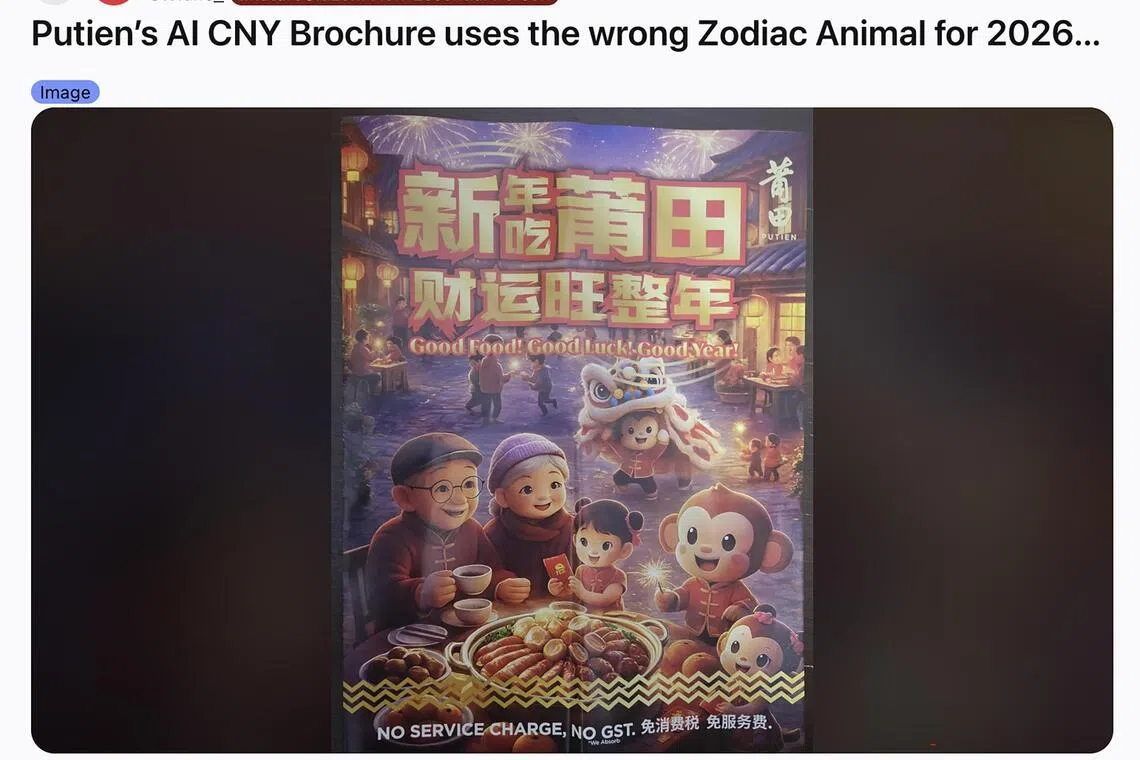

Most recently, Reddit users poked fun at an image used in a Chinese New Year brochure by local Fujian restaurant chain Putien containing telltale signs of AI use, such as deformed faces and hands.

Experts say the pace of advancements in AI is a double-edged sword.

Reddit users pointed out the telltale signs of AI use in a brochure for a local restaurant chain's Chinese New Year promotions.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM REDDIT

Mr Poon King Wang, chief strategy and design AI officer at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, says this can outstrip human capacity to keep pace and control, but also turbocharges human capability and creativity.

This means that one of the defining trends of 2025 was controversy over when and how AI should be used.

Nanyang Technological University penalised three students

Still, online discussion soon spiralled beyond this initial case, to questioning what constitutes unethical use of AI in education when generative AI has been incorporated into search engines and word processors.

Healthcare cluster National University Health System has been rolling out “AI-free” periods

And in July 2025, mental health professionals told ST that they had seen a rise in the number of patients who are using tools like ChatGPT as a confidant. They warn that while ChatGPT might dispense useful generic advice at times, it cannot address those with more complex needs.

At least one case of AI-induced psychosis

Dr Luke Soon, AI leader (digital solutions) at PwC Singapore, says that one of 2025’s most concerning trends is that AI has become embedded in day-to-day operations faster than many organisations fully understand its limits.

Many organisations are rolling out AI co-pilots and automation tools without understanding how these systems behave, how decisions are made or where accountability ultimately sits.

He adds that over time, how organisations govern the use of AI should evolve continuously, rather than remaining static. “The mixed signals seen today are consistent with a transition that is still unfolding.”

Reality distortion field

The term “reality distortion field” was originally used to describe Apple founder Steve Jobs’ ability to convince others that otherwise impossible goals were achievable, a term that has since been used to describe many other tech leaders and start-ups.

The year 2025 showed that AI, too, has its own reality distortion field, in that mixed evidence for its usefulness has not slowed down societal embrace of it.

A study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published in July 2025 found that 95 per cent of the 300-plus AI initiatives at companies studied failed to turn a profit.

“The mixed results are not unexpected. New technologies are adopted faster than organisations can redesign workflows and decision-making to fully realise their impact, and AI is no exception,” says Dr Soon.

Dr Kokil Jaidka, an associate professor at NUS’ department of communications and new media, points out that productivity gains from AI are uneven. “We are seeing real, measurable improvements in some domains, and much thinner returns in others.”

AI clearly boosts productivity in tasks that are routine, modular and easy to evaluate. For instance: decreasing the amount of time needed to complete certain programming tasks, write up a piece of text when working in customer support or perform complex scientific calculations for predicting new protein sequences.

“But those gains taper off quickly when tasks require judgment, contextual understanding or responsibility for outcomes,” says Dr Jaidka.

In many studies, experienced workers using AI produce work faster but not better – and sometimes worse. This is because they spend time checking, correcting and compensating for confident but incorrect output, she adds.

Productivity often shifts rather than increases: less time creating, more time supervising.

Even so, AI is an oft-cited reason for layoffs and restructuring, most visibly at tech giants like Amazon and Meta. In February 2025, Singapore bank DBS announced it would be cutting 4,000 temporary and contract roles across its 19 markets over the next three years due to AI adoption.

As the conversation increasingly turns towards reskilling and AI-related expertise, experts have also raised concerns over its impact on junior-level roles

“The imbalance that AI creates – shielding executives from automation, while lower-tier workers face displacement – reflects a deeper structural problem,” writes Mr Sam Ahmed, managing director of tech start-up Swarm AI, and Dr Sungjong Roh, assistant professor of communication management at SMU, in a commentary for ST.

“Strategic decisions on AI deployment are concentrated at the top, often made without accountability for their long-term societal consequences.”

Another area of concern is that recent advancements in AI have meant that AI-generated creations blend increasingly seamlessly into everyday life without drawing notice.

The rise of AI photo and video generation tools like OpenAI’s Sora and Google’s Nano Banana have meant social media feeds are awash with content that many users do not realise was AI-generated.

Indistinguishable from reality

AI’s reality distortion has created a world of increasingly persuasive scams

Dr Jaidka points out that the risk is not a sudden moment when AI images become indistinguishable from reality, but rather the gradual erosion of the boundary between what is real and not real.

The rise of AI-generated imagery means that the cues that people once relied on to discern the authenticity of a piece of content become increasingly meaningless.

This carries two key implications. First, AI-generated misinformation need not outright deceive. It can also subtly reinforce existing beliefs and biases in an environment where the truth matters less.

Second, the responsibility for verifying what is real and what is not has increasingly fallen upon individuals, as institutional safeguards lag behind advancements in AI.

The Singapore Police Force, Monetary Authority of Singapore and Cyber Security Agency of Singapore issued a joint advisory in March 2025 warning the public about the use of scams involving digital manipulation – in which AI deepfakes are used to impersonate others.

More recently, in November 2025, ST unearthed a swarm of inauthentic accounts operating on social media platform Threads. These accounts use what appear to be AI-generated images to lure real users into conversations with them, often drawing hundreds of comments with each post.

The posts, masquerading as attractive women and men, bear telltale signs of being “pig-butchering scams”, where scammers build trust with their victims before extracting money through fraudulent investments or cryptocurrency.

“Pig-butchering scams”, often found on social media and dating apps, get victims to send money over time.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM THREADS

Such inauthentic material has become intertwined with the business model of Meta, the company that operates Threads.

The social media firm internally projected around 10 per cent of its 2024 overall annual revenue (amounting to US$16 billion, or S$20.5 billion) comes from running advertisements for scams and banned goods, according to a Reuters investigation published in November 2025.

The company’s internal research from May 2025 also estimated that Meta’s platforms were involved in a third of all successful scams in the US.

Meta did not respond to a request for comment about the inauthentic pig-butchering material that ST found on its platforms. However, after the story’s publication, a representative of the public relations firm retained by the company reached out to question the ST report’s reference to the Reuters investigation.

As for the inauthentic AI-generated content, there was only radio silence.

Will the bubble pop in 2026?

Experts say the outlook for AI in 2026 is complicated.

Mr Poon says “we are both in a bubble and not in a bubble”, referring to growing commentary by experts about whether the current AI boom is akin to the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s.

“In cases where the outcomes are real, the boon is real,” he notes. “But in cases where there is just a lot of talk and inflated expectations, those are where there is a bubble brewing.”

Much of the hype around AI stems from how it produces output that looks competent, even when it lacks grounding, precision or accountability, says Dr Jaidka.

If AI leads to sustained improvements in decision quality, learning or institutional capacity, then the gains are real, she adds.

If, however, it mainly produces more content – that is less diverse – while creating more work spent on verifying machine output, it amounts to “a reallocation of cognitive labour rather than a productivity revolution”.