Ai Weiwei’s graphic memoir Zodiac is a mystical memory tour

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

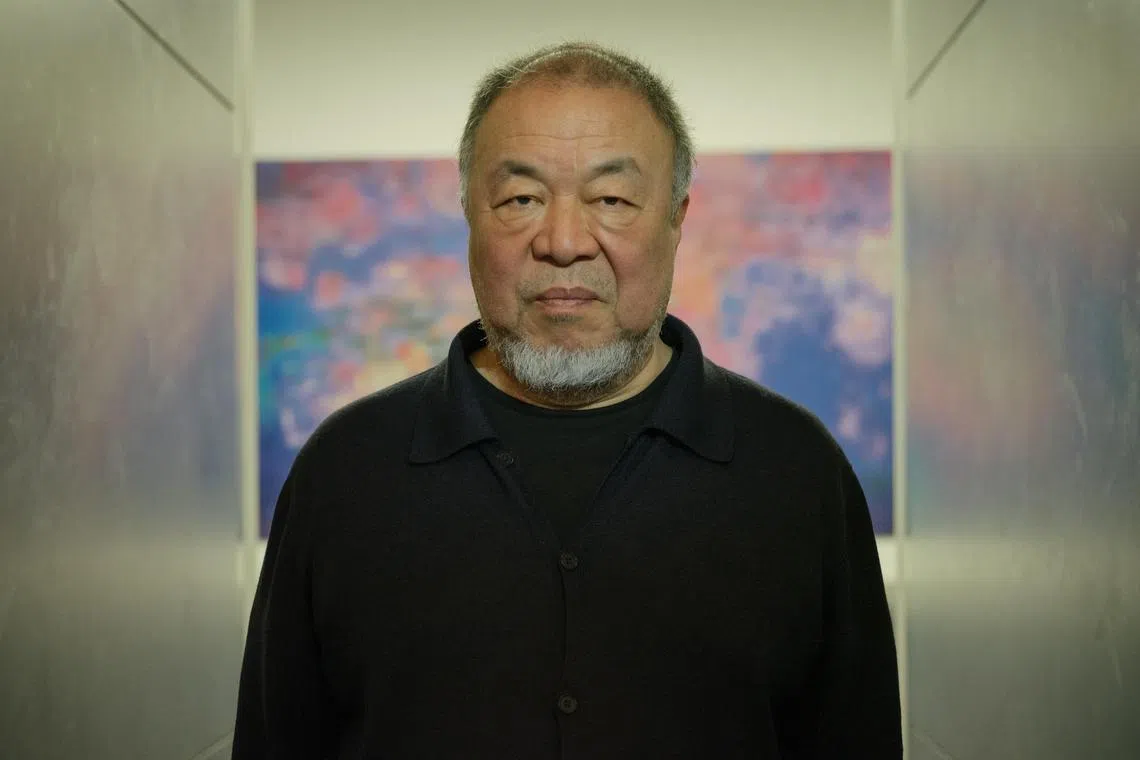

Artist Ai Weiwei with Water Lilies #2 (2022), a Lego-brick reinterpretation of Monet's masterpiece, at his show Know Thyself.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Follow topic:

BERLIN – With the Year of the Dragon, Ai Weiwei has released Zodiac, a “graphic memoir” of scenes from his career – both real (hanging with Allen Ginsberg, the OG of Beat poets, in 1980s Greenwich Village) and imagined (debating Mr Xi Jinping, China’s paramount leader).

Each chapter frames the Chinese artist’s take on traditional beliefs about the characteristics humans share with the 12 animals of the Chinese lunar calendar.

Italian cartoonist Gianluca Costantini’s intricate line drawings pair with Italian art curator Elettra Stamboulis’ comic-bubble text to help expand Ai’s lifelong campaign for free expression to a new medium for a new generation.

Ai, 66, spoke about home, parents and parenting, and the passage of time, all via video chat from Berlin, Germany.

A zodiac cycle ago, in 2012, “Twitter is my city”, you said. Now you live in Berlin; Cambridge, England; and Portugal. Where’s your city today?

Twitter was my city because it was the only place for my expression at that time. Since 2015, when I left China, conditions have changed. I was under such pressure in China. Suddenly, I came to the so-called free world, and Twitter was not so important. It was just one of the tools.

I consider nowhere home. Not China and not outside China. It is strange. I just came back from New York. I consider none of these cities home.

Home means you close your eyes and imagine the street and recognise a few names you grew up with. None of these places has this.

In Zodiac, you teach your son, Ai Lao, the legend of the Jade Emperor creating the calendar. What did you learn by explaining time?

Some say time is only an illusion. The illusion can be painful or it can be happy. Some live in the past and some struggle in the present. Someone may have no future.

It is hard to explain what time is about. The new generation needs some kind of reference when we talk about time. I can talk about the years I lived in Xinjiang or the time my father was dying, so I moved back to China from New York.

You really need events to illustrate time. My son will turn 15 soon, so his time will be in China, then Germany, then England. That is how he will understand it.

In a few Zodiac illustrations, we see your son speaking with an image of your father, poet Ai Qing, at his grave. Do you speak to him too?

It was an awkward situation. Ai Lao is a very independent boy. Perhaps it is due to his experiences. He has his own perspective and independent way of thinking.

Sometimes, we tried not to let him voice his feelings, but he bowed to my father’s image, which we never do – head down to the ground.

We never had that education, and we never taught him to do that. How could a child do that? This surprised me. But it was natural, to show this kind of respect.

I do not communicate with my father anymore. Not before he passed and not after. I regret I never asked him a solid question – what did he think about China or his time? I should have and it is too late.

Each generation bears the same situation. I would not want Ai Lao to ask me those questions. (But) his world will not be the same as mine. Probably my father never tried to pass his experience to me because he realised there was not much of a lesson to give to the next generation.

That is tragic. There is a strong sense of loss that carries more value than any material life. It is like being cut off from the most intimate relationship.

Some of Zodiac looks drawn from photographs and some seem to depict dreams. Describe the process and why you chose the graphic medium for the sequel to your 2021 prose memoir, 1000 Years Of Joys And Sorrows.

Gianluca, the illustrator, and his wife, Elettra, and I sat together. The idea was to gather things from my memory, like a timeline, and offer mystical stories from China’s past.

I explained it as a mix of memory and mythology. We thought this would relate not just my experience, but also general knowledge for whoever was interested.

It is a story with so much related to my situation that the publisher called it a memoir, but it is not. Memory is subjective. We choose some things to remember and lots to forget.

Most images in the book are related to photos because I post all my images on Instagram. They did the research. They asked questions and I answered. I never wrote a sentence, but I did edit.

All the dialogue in the book is based on my interviews. It is almost like an AI work.

Each animal represents a different characteristic. The mouse is a trickster and the ox is loyal. Does birth year determine personality and compatibility?

When we were growing up as communists, we did not have these superstitions. Gradually, I realised through my zodiac artwork the profound meaning of this mythology to help understand individuals and society.

It is very different from the West, where you turn to the stars for meaning.

The Chinese relate to the animals around them. Only one of them is mystical: the dragon.

This Year of the Dragon, 2024, is supposed to be the most uneasy, uncertain or dramatic year, which might be true.

Us Chinese, we all believe in these animals, which, strangely enough, have often turned out to be more reliable about personal character, about who to associate with. It is friendly knowledge, but the ones who believe in it really believe. NYTIMES