With AI, dead celebrities are working again – and making millions

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

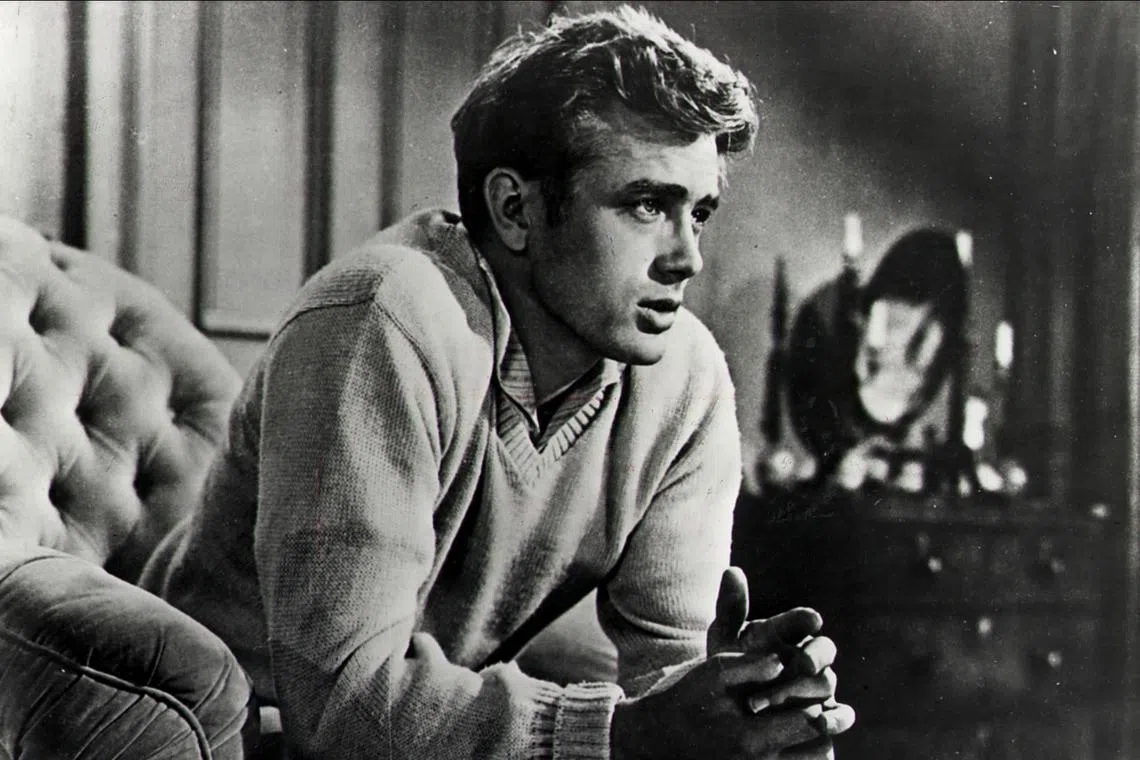

American actor James Dean's career may have ended tragically in 1955, but his estate is keeping his pay cheque alive through artificial intelligence.

PHOTO: WARNER BROS

NEW YORK – Can you think of a better way to get into the spirit of Halloween than listening to Washington Irving’s short story The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow read by the ghost of James Dean?

The actor’s career may have ended tragically in 1955, but his estate is keeping his pay cheque alive through artificial intelligence (AI).

Alongside the estates of Judy Garland, Laurence Olivier and Burt Reynolds, it signed with AI voice-cloning start-up ElevenLabs in July as part of the company’s “iconic voices” project.

The actors now narrate books, articles and other text material put into ElevenLabs’ Reader app.

From voice-over work to “digital human” acting jobs to immersive stage shows, AI is firing up the dead celebrity industry.

The industry has proved lucrative. Despite pop star Michael Jackson being about US$500 million (S$645 million) in debt at the time of his death, his estate has amassed a fortune of US$2 billion, according to People magazine, thanks to projects such as a jukebox musical and even posthumous albums featuring work made while he was alive.

Yet advances in AI mean a late artiste like Jackson can still generate new art.

Intellectual property lawyer Mark Roesler has represented over 3,000 celebrities, most of whom are dead, and made some 30,000 deals on their behalf since founding his company CMG Worldwide more than four decades ago.

Among current clients including American civil rights activists Rosa Parks and Malcolm X, he has negotiated musician Jerry Garcia his own ElevenLabs deal.

There are two key ways a living celebrity makes money, Mr Roesler says.

The first is personal services, which, for a musician like Prince, would have been income from his concerts and songs.

The second is intellectual property, which is independent of those services and could be anything from the copyright of music to pictures.

When a celebrity dies, their personal services revenue expires immediately, leaving to their estate just the intellectual property revenue which, Mr Roesler found, used to decline on average by 10 per cent annually, but now can rise. “I’ve been assisted by all the technological changes, like AI.”

Mr Travis Cloyd, founder and chief executive of Worldwide XR – where Mr Roesler is chairman – has cast the late James Dean in the movie Return To Eden, currently in production.

With dead celebrities, there are now two pathways for film-makers, Mr Cloyd says: “You could either hire an actor, or now, because of the technology, you can create a digital human of James Dean.”

The latter process begins with a base of source material, so-called legacy assets that even include family videos.

These are put through machine learning to create a digital model of the actor.

From there, other elements are created by using body doubles for skin texture and movement, and vocals get layered on top.

It is similar to how actors Paul Walker (Furious 7) and Peter Cushing (Rogue One: A Star Wars Story) made their controversial CGI appearances almost a decade ago. A large role by Ian Holm, who died in 2020, in this summer’s Alien: Romulus, inflamed critics and did little to quell the ethical debate around AI, even though his widow, children and estate signed off.

Hollywood is slowly getting on board after the actors’ and writers’ strikes in 2023 brought the industry to a standstill over a number of issues, chief among them AI.

In August, SAG-Aftra, the primary union for actors, reached a deal allowing brands to replicate living actors’ voices in AI audio ads on a job-by-job basis.

For dead ones, Mr Cloyd says, enormous demand will dictate the terms. The potential for AI projects to become the main driver of income for celebrities’ estates in the next five years is massive, he says.

Consider ABBA Voyage, which opened in London in May 2022 and has been making more than US$2 million a week with concerts featuring de-aged, virtual reality avatars of the Swedish pop stars. Although the foursome collaborated on the show and were all still alive as at press time, these CGI renderings could theoretically keep minting money for their estates long after their deaths.

Not everyone is convinced.

Mr Jeff Jampol, who manages “inactive artistes” including Janis Joplin and The Doors, sees AI as a “non-starter”.

He has turned down offers to replicate singer Jim Morrison’s voice and casts the technology as a fad akin to non-fungible tokens, or NFTs. “There’ll be something else next,” he says, noting his decades in the industry seeing “waves come and go”.

But mostly, “I can’t put anything in Jim Morrison’s mouth that he didn’t say ever. That would be a travesty”, he added.

Ms Svana Gisla, the Emmy- and Grammy-nominated co-producer behind ABBA Voyage, which did not use AI in cloning the singers, thinks there is one key place the new technology falls short.

“We will always be seeking that emotional connection that lies within that communication that art brings,” she says, “and AI will never provide that communication or replace artistry in any form.”

Perhaps the biggest test of AI will arrive next spring, when Elvis Evolution premieres at ExCeL London and sees the King of Rock ’n’ Roll performing for the first time in more than 45 years.

For the almost two-hour immersive biopic – think piped-in scents of earthy cotton fields and cranked-up humidity to evoke rural Mississippi – capturing the icon’s stage presence in hologram form has been no easy task, says Mr Andrew McGuinness, founder and CEO of Layered Reality, the show’s producer.

“It’s not a kind of fabrication or the work of a digital artist,” he says. “It actually comes from his real-life performances, his real-life facial movements, his real-life voice structure”, and it takes hundreds of hours of performance and home videos fed into AI software to create his digital double. BLOOMBERG