News analysis

Why global investors are watching what Japan does next

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

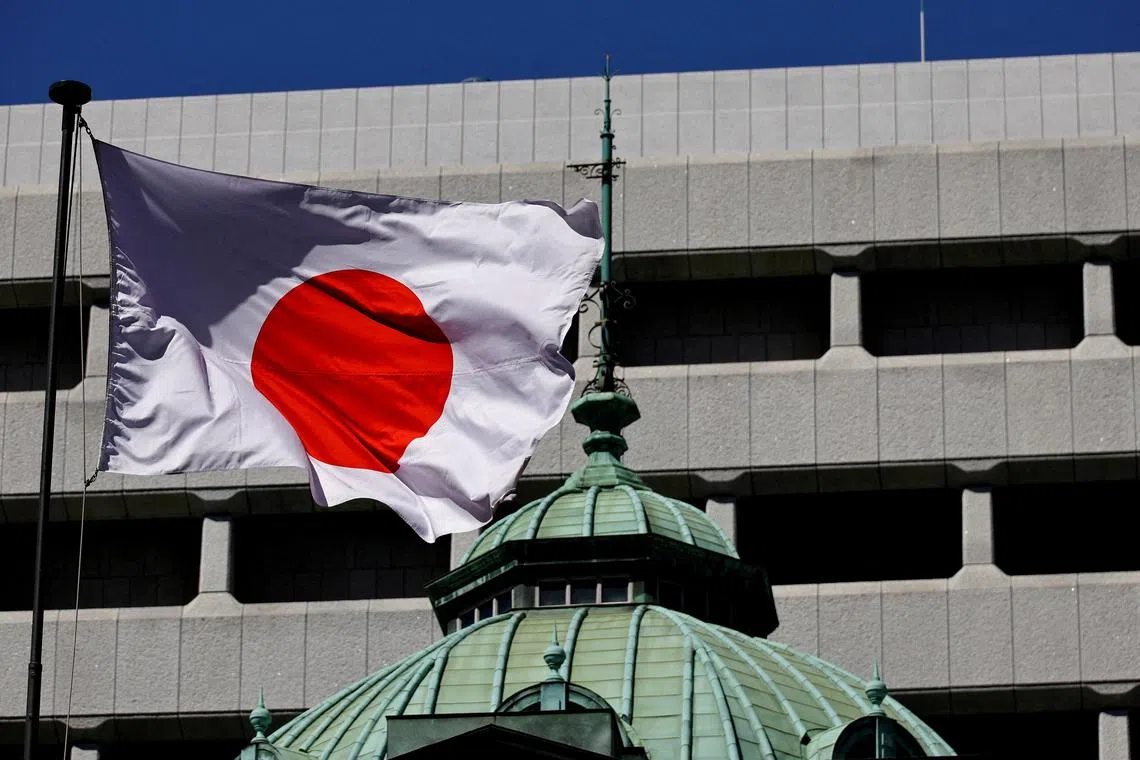

Economists believe Japan's central bank might raise rates again at its upcoming meeting, which concludes on July 31.

PHOTO: REUTERS

NEW YORK - Japan’s central bankers meet this week, and what they decide has the potential to move markets around the world.

That is because Japan is an outlier among major economies. While policymakers in the United States and elsewhere are either preparing to cut interest rates

“Japan is in a different world,” said Mr Kei Okamura, a portfolio manager based in Japan at investment firm Neuberger Berman.

The BOJ cut interest rates below zero per cent in 2016 and kept them there until March 2024, when it announced the first rate increase in 17 years, as the economy showed signs of recovery from anaemic growth and low inflation. Economists believe the central bank might raise rates again at its upcoming meeting, which concludes on July 31.

Policymakers at the Federal Reserve will meet later on the same day to consider a rate cut to take the brakes off the US economy. Even if both central banks keep rates steady on July 31, most investors believe that they will act before too long, and market-based interest rates have moved accordingly.

The combination of a rise in Japanese interest rates and a decline in US rates would compress a big gap – or spread, in market lingo – that investors have sought to exploit. A lot of money moves around the world based on tiny shifts in rate spreads: The dollar-yen is the second-most commonly traded pair of currencies in the world, after the dollar-euro, accounting for more than US$1 trillion (S$1.3 trillion) in foreign exchange transactions per day.

Relatively low interest rates in Japan have been the primary reason for persistent weakness of the yen, which recently hit its lowest levels against the US dollar in decades. That allowed investors – particularly Japanese investors – to use cheap yen to invest in higher-yielding assets abroad, in what is known as the “carry trade”. But as rates in Japan and elsewhere shift, this trade could unwind – the yen has bounced up sharply versus the dollar in the past two weeks – with reverberations for stocks, bonds and other markets. Money could shift out of the US, where Japanese investors are some of the biggest holders of US government debt and major lenders to companies, potentially putting Wall Street under pressure.

A rising yen also hurts Japan’s stock markets, where export-oriented companies dominate. The Nikkei 225 index set a series of record highs in 2024, but has stumbled in recent weeks, shedding more than 10 per cent from its peak in mid-July.

Market moves could be particularly pronounced in the summer months, when trading volumes are typically lower, amplifying the trading that does take place.

Mr George Goncalves, head of US macro strategy at MUFG Securities, warned of turbulence over the coming month, especially in currency markets as the yen strengthens along with higher Japanese interest rates.

“It is lining up in a way where it can turn and accelerate more if we get a hawkish BOJ and a dovish Fed,” he said.

However, others caution that central bankers in Tokyo and Washington are in no rush to shift policy, wary of stamping out the embers of growth (with rate increases in Japan), or reigniting inflation (with rate cuts in the US).

“It will be a very gradual process,” Mr Okamura said, adding that “global investors are keen to see how this plays out”. NYTIMES