US pours money into chips, but even soaring spending has limits

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

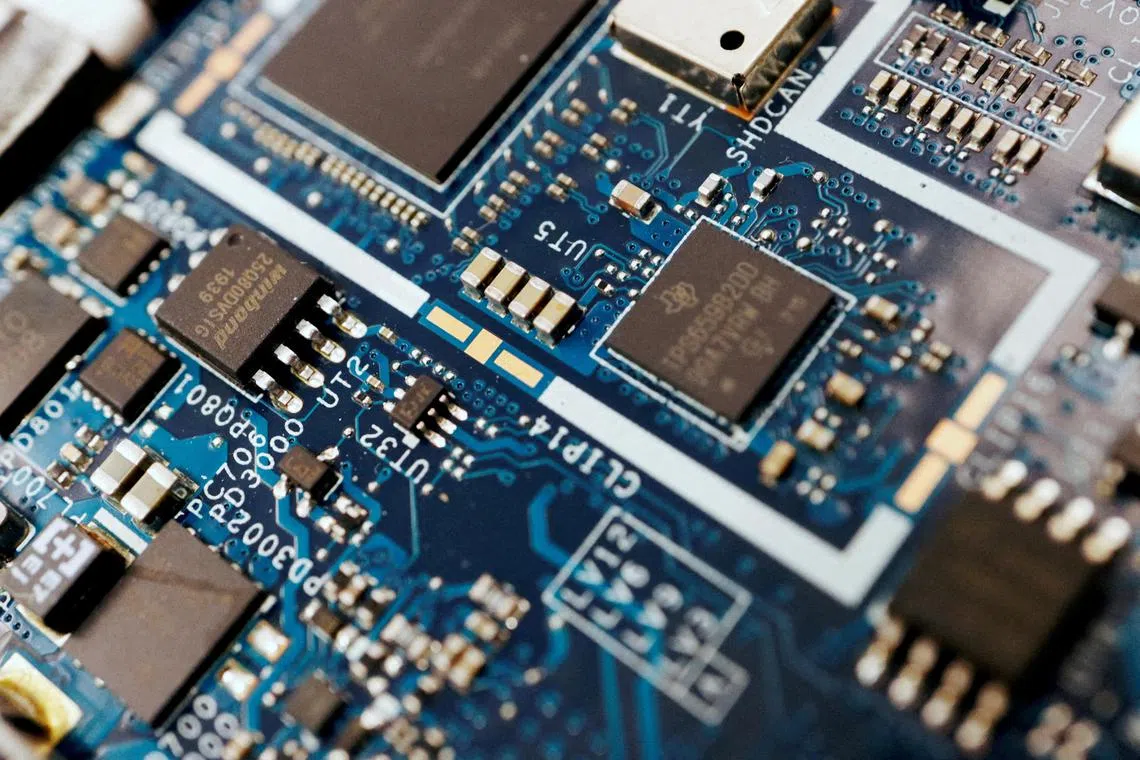

Chips are an essential part of modern life even beyond the tech industry’s creations, from military gear and cars to kitchen appliances and toys.

PHOTO: REUTERS

SAN FRANCISCO – In September, chip giant Intel gathered officials at a patch of land near Columbus, Ohio, where it pledged to invest at least US$20 billion (S$26.8 billion) in two new factories to make semiconductors.

A month later, Micron Technology celebrated a new manufacturing site near Syracuse, New York, where the chip company expected to spend US$20 billion by the end of the decade and eventually perhaps five times that.

In December, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) hosted a party in Phoenix, where it plans to triple its investment

The pledges are part of an enormous ramp-up in US chipmaking plans over the past 18 months, the scale of which has been likened to Cold War-era investments in the space race.

The boom has implications for global technological leadership and geopolitics, with the United States aiming to prevent China from becoming an advanced power in chips, the slices of silicon that have driven the creation of innovative computing devices like smartphones and virtual reality goggles.

Today, chips are an essential part of modern life even beyond the tech industry’s creations, from military gear and cars to kitchen appliances and toys.

Across the nation, more than 35 companies have pledged nearly US$200 billion for manufacturing projects related to chips since the spring of 2020, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association, a trade group.

The money is set to be spent in 16 states, including Texas, Arizona and New York, on 23 new chip factories, the expansion of nine plants, and investments from companies supplying equipment and materials to the industry.

The push is one facet of an industrial policy initiative by the Biden administration, which is dangling at least US$76 billion in grants, tax credits and other subsidies to encourage domestic chip production. Along with providing sweeping funding for infrastructure and clean energy, the efforts constitute the largest US investment in manufacturing arguably since World War II, when the federal government unleashed spending on new ships, pipelines and factories to make aluminium and rubber.

“I have never seen a tsunami like this,” said Mr Daniel Armbrust, former chief executive of Sematech, a now-defunct chip consortium formed in 1987 with the Defence Department and funding from member companies.

President Joe Biden has staked a prominent part of his economic agenda on stimulating US chip production, but his reasons go beyond the economic benefits. Many of the world’s cutting-edge chips today are made in Taiwan, the island to which China claims territorial rights. This has caused fears that semiconductor supply chains may be disrupted in the event of a conflict – and that the US will be at a technological disadvantage.

The new US production efforts may correct some of these imbalances, industry executives said – but only up to a point.

The new chip factories would take years to build and might not be able to offer the industry’s most advanced manufacturing technology when they begin operations. Companies could also delay or cancel the projects if they are not awarded sufficient subsidies by the White House. And a severe shortage in skills may undercut the boom, as the complex factories need many more engineers than the number of students who are graduating from US colleges and universities.

The bonanza of money on US chip production is “not going to try or succeed in accomplishing self-sufficiency”, said Dr Chris Miller, an associate professor of international history at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and the author of a recent book on the chip industry’s battles.

White House officials have argued that the chipmaking investments will sharply reduce the proportion of chips needed to be purchased from abroad, improving US economic security.

At the TSMC event in December, Mr Biden also highlighted the potential impact on tech companies like Apple that rely on TSMC for their chipmaking needs, saying that “it could be a game changer” as more of these companies “bring more of their supply chain home”.

Still, the ramp-up is unlikely to eliminate US dependence on Taiwan for the most advanced chips. Such chips are the most powerful because they pack the highest number of transistors onto each slice of silicon, and they are often held up as a sign of a nation’s technological progress.

Intel long led the race to shrink the size of transistors so more could fit on a chip. This pace of miniaturisation is usually described in nanometres (nm), or billionths of a metre, with smaller numbers indicating the most cutting-edge production technology. Then, TSMC surged ahead in recent years.

But at its Phoenix site, TSMC may not import its most advanced manufacturing technology. The company initially announced that it would produce 5nm chips at the Phoenix factory, before saying last month that it would also make 4nm chips there by 2024 and build a second factory, which will open in 2026, for 3nm chips.

It stopped short of discussing further advances.

In contrast, TSMC’s factories in Taiwan began producing 3nm technology at the end of 2022. By 2025, factories in Taiwan will probably start supplying Apple with 2nm chips,

TSMC and Apple declined to comment.

Whether other chip companies will bring more advanced technology for cutting-edge chips to their new sites is unclear.

Samsung Electronics plans to invest US$17 billion in a new factory in Texas, but has not disclosed its production technology. Intel is manufacturing chips at roughly 7nm, although it has said its US factories will turn out 3nm chips by 2024 and even more advanced products soon after that.

The chipmaking boom is expected to create a jobs bonanza of 40,000 new roles in factories and companies that supply them, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association. This would add to about 277,000 US semiconductor industry employees.

But it will not be easy to fill so many skilled positions. Chip factories typically need technicians to run factory machines and scientists in fields like electrical and chemical engineering. The talent shortage is one of the industry’s toughest challenges, according to recent surveys of executives. NYTIMES