US creates high-tech global supply chains to blunt risks tied to China

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The core elements of the plan include getting foreign companies to invest in chipmaking in the US and finding other countries to set up factories to finish the work.

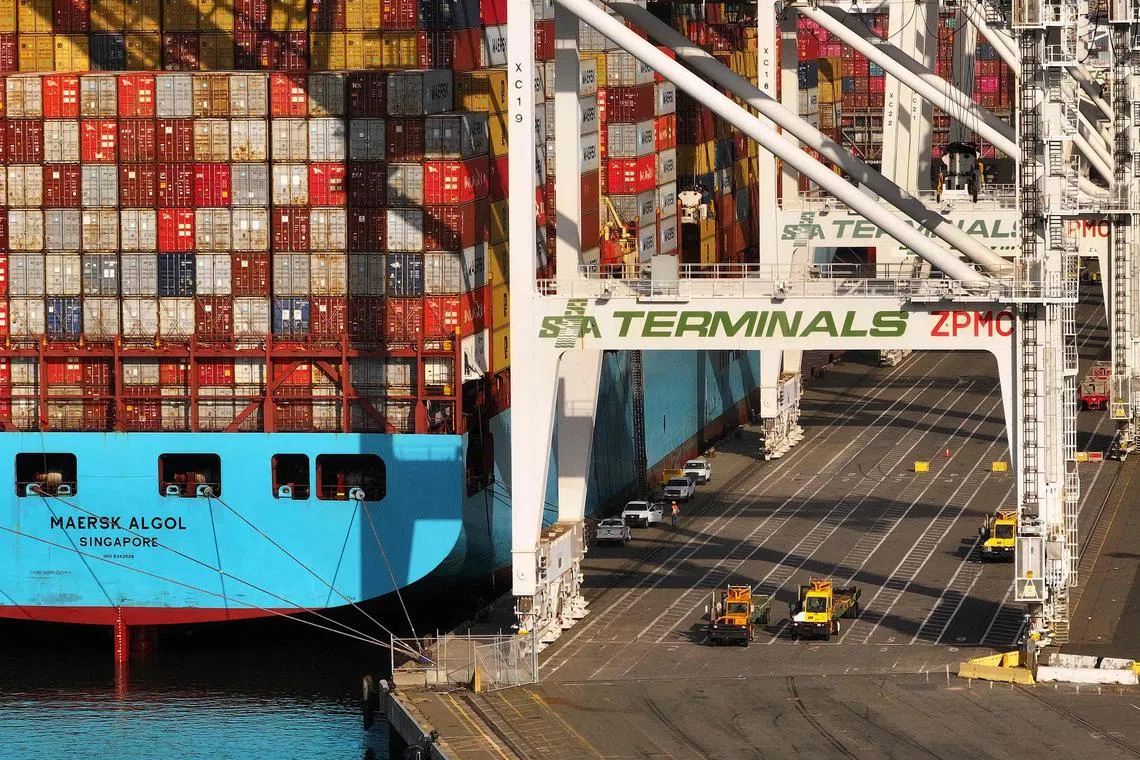

PHOTO: AFP

WASHINGTON – If the Biden administration had its way, far more electronic chips would be made in factories in, say, Texas or Arizona.

They would then be shipped to partner countries, such as Costa Rica, Vietnam or Kenya, for final assembly and sent out into the world to run everything from refrigerators to supercomputers.

Those places may not be the first that come to mind when people think of semiconductors. But administration officials are trying to transform the world’s chip supply chain and are negotiating intensely to do so.

The core elements of the plan include getting foreign companies to invest in chipmaking in the United States and finding other countries to set up factories to finish the work. Officials and researchers in Washington call it part of the new “chip diplomacy”.

The Biden administration argues that producing more of the tiny brains of electronic devices in the US will help make the country more prosperous and secure.

President Joe Biden boasted about his efforts in his interview on July 5 with ABC News, during which he said he managed to get South Korea to invest billions of dollars in chipmaking in the US.

But a key part of the strategy is unfolding outside America’s borders, where the administration is trying to work with partners to ensure that investments in the US are more durable. If the nascent effort progresses, it may help the administration meet some of its broad strategic goals.

It wants to blunt security concerns involving China

“The focus has been to do our best to expand the capacity in a diverse set of countries to make those global supply chains more resilient,” said Professor Ramin Toloui, a Stanford University professor who recently served as assistant secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, which is at the forefront of diplomatic efforts to set up new supply chains.

The administration aims to do that not just for chips, but also for green energy technology

Mr Biden and his aides say that dominance by Chinese companies is a national security issue, as well as a human rights problem, given that some of the manufacturing takes place in Xinjiang, a region of China where officials reportedly force members of some Muslim ethnic groups to work in factories.

Over three years of the Biden administration, the US has attracted US$395 billion (S$530 billion) of investment in semiconductor manufacturing and US$405 billion for making green technology and generating clean power, Prof Toloui said.

Many of the companies investing in that kind of manufacturing in the US are based in Asian economies known for their tech industries – Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, for instance – and in Europe.

One is SK Hynix, a South Korean chipmaker that is building a US$3.8 billion factory in Indiana. The State Department says that the project is the largest-ever investment in that state and that it has the potential to bring more than 1,000 jobs to the region.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken mentioned that project in a speech in June at a conference in Maryland aimed at encouraging foreign investment in the US. And he underscored how he hoped legislation enacted by Mr Biden would draw foreign investment to US high-tech manufacturing by “modernising our roads, our rail, our broadband, our electric grid”.

The policy efforts, he added, are aimed at “strengthening and diversifying supply chains, turbocharging domestic manufacturing, spurring key industries of the future, from semiconductors to clean energy”.

The Commerce Department has also played a major role in the effort to shore up the chip supply chain and is disbursing US$50 billion to companies and organisations to research, develop and manufacture chips.

Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo led an in-depth study of global chip supply chains to identify vulnerabilities and has worked with foreign governments to discuss opportunities for additional investments overseas.

The topic was a focus of Ms Raimondo’s trip to Costa Rica in spring 2024 as she met local officials and executives from Intel, which runs a factory there. (Prof Toloui spoke at a semiconductor manufacturing conference in Costa Rica in January.) She also discussed diversifying the semiconductor supply chain on trips to Panama and Thailand.

But reworking global supply chains so that they are less dependent on East Asia will be a challenge. East Asian chip factories offer more cutting-edge technology, a larger pool of talented engineers and lower costs than American factories are projected to.

Taiwan produces more than 60 per cent of the world’s chips and nearly all of the most advanced chips, which are used in computers, smartphones and other devices. By comparison, the US semiconductor industry could face a shortage of up to 90,000 workers over the next few years, according to several estimates.

Governments in China, Taiwan, South Korea and elsewhere are also aggressively subsidising their own chip industries.

Still, billions of dollars of new US investment are expected to somewhat shift global supply chains. The US share of global chip manufacturing is projected to rise to 14 per cent by 2032, from 10 per cent today, according to a May report from the Semiconductor Industry Association and the Boston Consulting Group.

Some administration officials have engaged in a more coercive form of chip diplomacy to prevent China from developing versions of American technology. That approach has focused on persuading a handful of countries – Japan and the Netherlands, in particular – to stop companies from selling some chipmaking tools to China.

Mr Alan Estevez, who leads the bureau within the Commerce Department in charge of export controls, visited Japan and the Netherlands in June to try to persuade the countries to block companies there from selling certain advanced technology to China.

By contrast, Prof Toloui and his aides have flown around the world to scout out countries and companies that might want to invest in the American industry and set up factories that would form the end point of the supply chain. Prof Toloui said his bureau’s work was an element of Mr Biden’s recent enactment of legislation to create more manufacturing jobs in the US, including the infrastructure Act and the Chips and Science Act.

The chips Act includes US$500 million of funding annually for the administration to create secure supply chains and to protect semiconductor technology. The State Department draws on that money to find countries for supply chain development. Officials are organising studies on a range of countries to see how infrastructure and workforces can be brought up to certain standards to ensure smooth chip assembly, packaging and shipping.

The countries now in the programme are Costa Rica, Indonesia, Mexico, Panama, the Philippines and Vietnam. The US government is bringing in Kenya.

Job training is a priority in this supply chain creation, Prof Toloui said. He has talked to Arizona State University about being a partner with overseas institutions to develop training programmes. One such institution is Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City, which he visited in May.

Mr Martijn Rasser, managing director of Datenna, a research firm that focuses on China, said this network of alliances is a strategic advantage that the US has over China.

For the US to try to do everything itself would be too expensive, he said. And going it alone would not recognise the reality that technology today is much more diffused globally than it was a few decades ago, with various countries playing important roles in the chip supply chain. NYTIMES